Advanced technology for control and information processing, often computerised, has infiltrated almost explosively into more and more areas. In spite of optimistic expectations, this has often led to deteriorating work conditions for the people involved. This has been described in a large number of ergonomic and social/psy – chological studies.

Within the process industries, it is found that the U-shaped curve expresses the relationship between work motivation on the one hand and technical development on the other (see Figure 13.4). It seems as if work motivation in the modern, computerised, highly-automated process industries is rather low, and in many cases is approaching that of ‘assembly-line’ jobs. It is also found (Figure 13.5) that variations in work load have become even greater and that the low-load periods have become longer and even lower. Automation has often led to a severe reduction in job content and an increased degree of outside control (due, among other factors, to the increase in the degree of continuity in process control) with the introduction of computer technology.

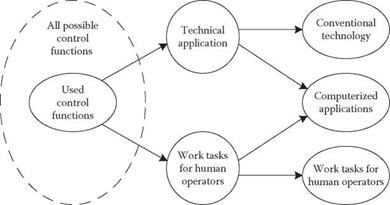

Figure 13.6 attempts to show in a highly simplified way how computerisation is traditionally carried out. Figure 13.6 is not just relevant to the process industry, but probably has considerable validity in general application. The reason for this is mainly that technical people working on automation development have hitherto worked fairly conventionally. As such, they have taken a much-too-limited view of people and their work requirements. The view was perhaps even mistaken. The starting point has been the old technology, what it knew and what it did. The developers considered the tasks the old technology could carry out and then determined the jobs of the human operators. Using this as a background, advanced computerised technology has been allowed to take over the work both of the conventional technology and of the person. One obvious consequence of this is that the content of people’s jobs is drastically reduced.

![]()

|

FIGURE 13.4

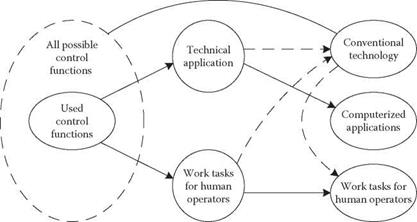

It is interesting to note in this connection that the new computerised technology has intrinsically more ‘power’, and the ability to do much more than could be done by the old system and the human operator. In order to control a technical process optimally, there are theoretically an infinite number of functions available. The human operator and traditional technology, with their limited abilities and resources, can only make use of a small part of these. Modern computer technology has the potential to do other tasks; it is therefore possible to utilise functions that were not

|

The old conventional The new computerized application application

FIGURE 13.6 Conventional approach to the design of automation. |

|

FIGURE 13.7 Alternative approach to the design of automation. |

earlier used (see Figure 13.7). With a little imagination, new and unconventional solutions for controlling processes could thus be found.

In our research (Ivergard et al., 1982; Hunt, Burvall, and Ivergard, 2004) we have shown examples of how it has been possible, with the aid of computerisation, to give the operator refined information on the functions, strengths, and weaknesses of the process. New, advanced computer technology can give the operator better information, and at the same time new abilities in the controlling of the process. In this way, the operator can be included right in the centre of the process. Actually the operator is the most central function. The operator is given a decisive role in determining the production function and the production results in terms both of quality and speed. The operator should thus be able to become even more important than before.

In addition, the operator can be given the opportunity to build up new forms of job skill and also the possibility of reinforcing the old, traditional job skills based on his or her personal knowledge and experience of the process. In other words, the operator does not need to be a mechanical cog in the process but can take the central control function. With this form of alternative development, the job will become at least as interesting and meaningful as the previous work—that is, the job becomes of value.

Apart from making the design of the job interesting and meaningful for the individual, the operator can, with the aid of computerisation, get a better insight and overview of the whole process. The computerised system can provide an overview of the production results and economic aspects within the company, which increases the operator’s ability to take a meaningful part in the overall decision-making processes in the company.

It is outside the scope of this short review to discuss in any more detail the background as to why this line of reasoning is actually true. Some of the reports published by Ergolab (Ivergard et al., 1982) give a somewhat better exposition of this background and the reasoning behind it. Comparative studies of the effects of computerisation within manufacturing industries have been carried out in Great Britain and Germany (Sorge et al., 1982). These studies also show that computerisation does not need to lead to any downgrading of jobs on the factory floor. Some related aspects about learning and creativity in control room work are also discussed in Chapter 11.