of Bernhardt Design, “but would be produced in the real world for market, and they would have the complete experience as if they had graduated and they were working for a client.”

of Bernhardt Design, “but would be produced in the real world for market, and they would have the complete experience as if they had graduated and they were working for a client.”

This idea of reality-dose-as-educational-opportunity started when Helling decided to get Bernhardt more closely connected with those who are on their way to becoming the next generation of professional designers; it grew into a bit of phenomenon for both the students and the company. “I have been wanting to be involved in the educational process somehow, some way, for some time,” says Helling. “But projects with companies working with educational institutions are generally about competition, looking at the future, creating an exhibition, or doing one-off work. I talked to lots of students, and one day it hit me that what we could bring to the table that would benefit students most would be if we could provide a real-time, real-life experience of what it’s like to work with a client and manufacturer.” Helling approached Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California not only because of its reputation for excellence, but because of the nature of its students. “The student body is a little older,” he says, “and it’s a very professional school. The practicality of life is stressed there in addition to pure creativity.”

Working with David Mocarski, chairman of the Environmental Design Department, they created a two-semester course. The first semester took twenty-two students from research and concepting through prototyping a piece of furniture. According to Helling, “They started by researching the American furniture market. They saw what was out there, what people wanted. Then they researched our company because they had to design something appropriate for us. Then they started down the design process, doing broad-based conceptuals, refining that into computer models, and moving into small-scale modeling. Ultimately, their final task at the end of the first semester was to go out into Los Angeles and find full-scale prototyping. They only had to make one,” he notes. “They had to do it because they learned so much in that process about what kind of accommodations had to be made to their ideas just to produce one.”

This semester ended with a presentation of their prototypes to their client and patron, Bernhardt. The students knew that if their work was selected, they’d move into semester two, which would take their designs through the manufacturing process, all the way to market, and include lessons on marketing and public relations, as well as royalties. The results of this first class far exceeded Helling’s expectations: “Our goal was to bring three products to market. I was prepared to take none, and originally thought I’d take five or six. We chose ten. We chose those we thought were most likely to be viable and marketable products.”

|

|

|

|

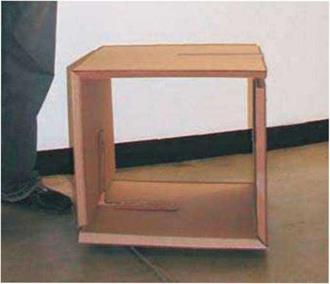

(^)The first full-scale mock-up was made in cardboard to check size and other details necessary for Franco to get her first real prototype made. Credit: Ana Franco

(^)The first full-scale mock-up was made in cardboard to check size and other details necessary for Franco to get her first real prototype made. Credit: Ana Franco

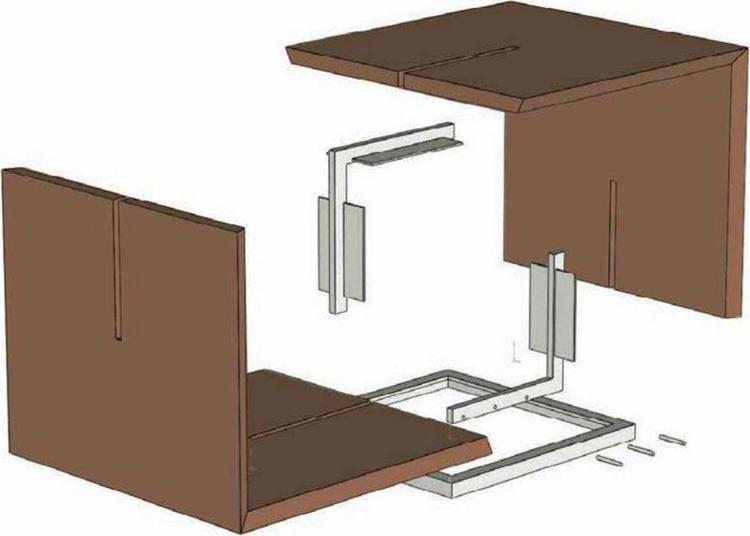

(Q) For a prototype, Franco used welded plates on the metal strips to connect them to the wood. In production, Bernhardt used a much more ingenious method to make the connections totally invisible. Credit: Ana Franco

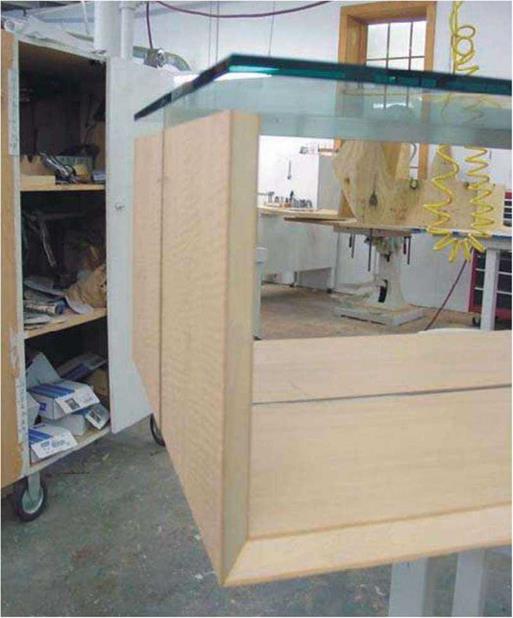

(^) Franco’s first prototype, the final assignment of the first semester, was constructed of veneered 1" (2.5 cm) MDF (medium density fiberboard). Credit: Ana Franco

©In the Bernhardt factory, a CNC (computer numerical controlled) milling machine is used to cut the groove for the metal band in a piece of wood. Credit: Bernhardt Design

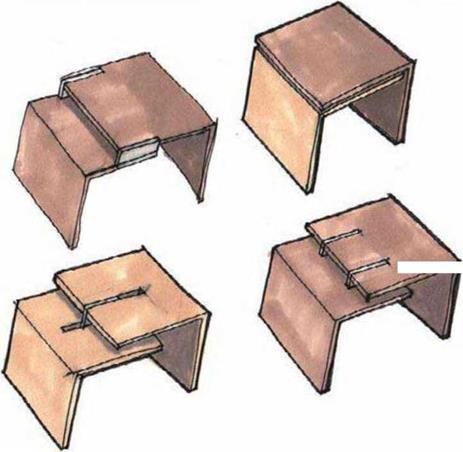

©The table parts are secured with a process called polarization, whereby pins that are countersunk into the wood and run through holes in the metal strip are magnetized to create a completely invisible connection. Credit: Bernhardt Design

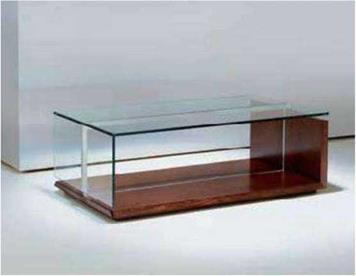

In the fully assembled table, the glass top appears to float above the wooden base, magically suspended by a slice of metal. Credit: Bernhardt Design

One of those chosen was the Float Table by Ana Franco. Her design process began by thinking about the client: “I started with words that describe Bernhardt. This was an opportunity to look at the company aesthetic, which is elegant, sophisticated, airy. I used these words to spur me onto to some ideas. Their products are also really architectural, and I thought this was a great opportunity to play with simple but interesting forms. We were told that Bernhardt uses wood, and it would be better to incorporate that, rather than asking them to do something they don’t do. That was part of the lesson—to stick with the materials and process they already have ready access to.”

Franco started sketching, making models, and fighting to find the right form for her ideas. At several points in the process, she was sure she wouldn’t make the cut. “The brief was to do table or chairs, and I did both. I kept showing them and showing them, and I didn’t get any bites,” she says. Then things started to change. “Jerry liked an idea I had of folded wood connected with a sliver of metal. I kept struggling, thinking, this is the one he’s interested in, and I should pursue this one, but I kept thinking it’s too simple. This was the biggest challenge: to create something with a very simple form but still with one interesting gesture. One weekend, working with a model, I turned one of the folds over, and turned the table into a cube. My teacher said, ‘Jerry will love this.’”

Jerry did. In fact, he points out that Franco’s design of a table in wood, metal, and glass was one of the few that had almost no changes from concept to final production. But Franco had some

|

|

doubts along the way about whether they would be able to execute on her vision: “Jerry told me at the final crit that the table would never look as good in final production,” she says. Then she quickly adds, “And he was wrong.” She feels that part of the success of this college/corporate partnership is the unique energy students bring to the process. “To get chosen,” she points out, “we were to push the boundaries, but not beyond what Bernhardt does. We brought a kind of gutsiness to it. We brought that kind of enthusiasm, where we wanted to challenge them, but with a cap on it. To me, more constraints make for better design.”

Not only have these students had the unique learning experience as well as they financial rewards of seeing their work produced, but they have also enjoyed a surprising amount of publicity and awards. In addition to write ups in the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, and Newsweek, they received a profile in Metropolis entitled, “The Magnificent 7”, and were given the Best New Designer award by the ICFF (International Contemporary Furniture Fair), as well as a Best in Competition prize and two gold awards in seat – ing/sofa and lounge and tables/occasional at the NeoCon trade fair.

Naturally, Helling says Bernhardt Design is committed to continuing their investment with the students of Art Center College of Design. “We got a great experience, they got a great experience, and we got good products. So in taking a chance like this, the payoff was great for everyone. I’ve learned that you can take the risk, and it can work and be wonderful for everyone involved.”