In each of these approaches, there are both formal and informal influences. While Lehrecke didn’t attend architecture school, he does have a professional background in both architecture and design and grew up in the house of an architect. And he has been a long-time collector of furniture. Most important, he doesn’t mind getting his hands dirty. “I started making things and looking at how machines work and how machines affect the way things are made and the way materials affect the way things are made,” he says. Referring to his Exploding Log Shelving unit, he concludes, “This piece is a perfect example of me leaning towards the mate – rials-and-the-machine” design sensibility.”

In each of these approaches, there are both formal and informal influences. While Lehrecke didn’t attend architecture school, he does have a professional background in both architecture and design and grew up in the house of an architect. And he has been a long-time collector of furniture. Most important, he doesn’t mind getting his hands dirty. “I started making things and looking at how machines work and how machines affect the way things are made and the way materials affect the way things are made,” he says. Referring to his Exploding Log Shelving unit, he concludes, “This piece is a perfect example of me leaning towards the mate – rials-and-the-machine” design sensibility.”

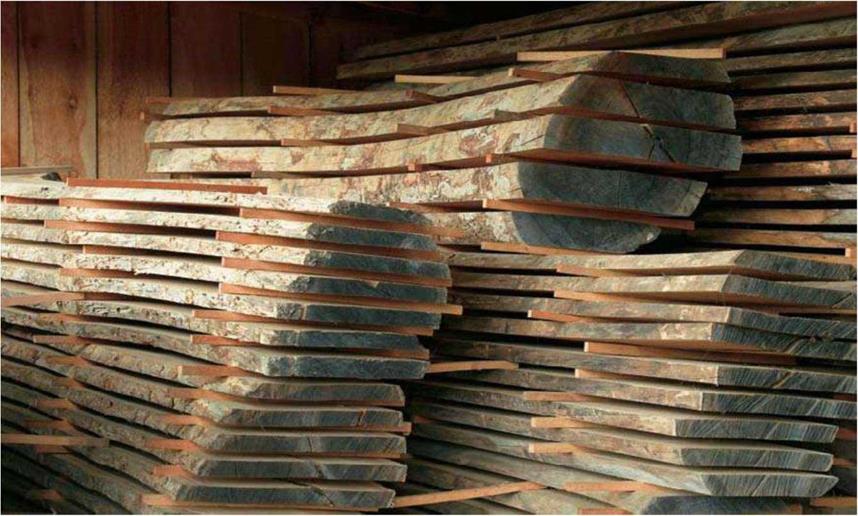

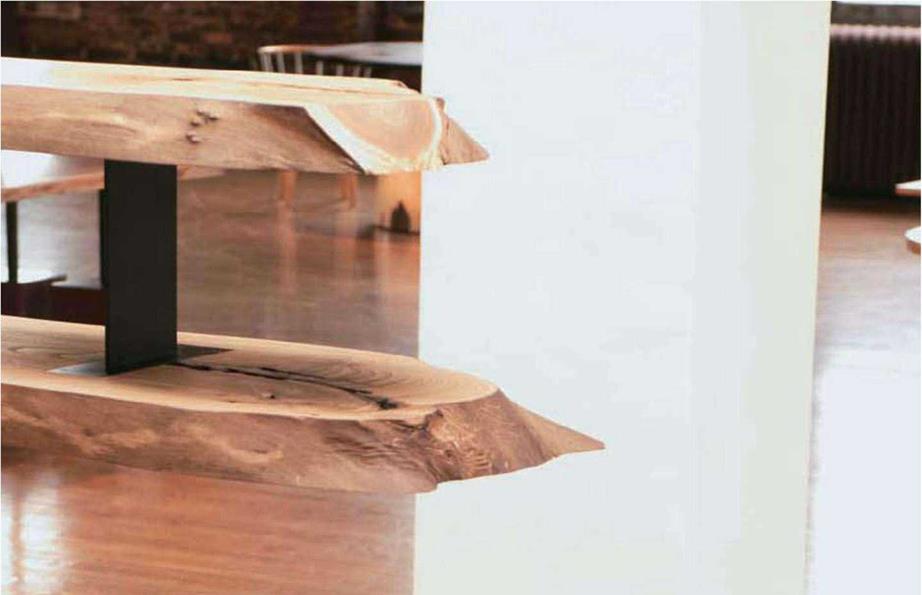

The Exploding Log Shelf, like Lehrecke himself, is a product of its environment. After working in the highly urban setting of Brooklyn, New York, for twelve years, he moved his studio eight years ago to the countryside. “I bought an old church, and when the ten-acre field behind the church became available, I started warehousing logs,” he explains. “I was doing everything from scratch, getting the logs, milling them, drying them, and going out to work with the sawyers. We’d take a log and put it up on this portable band saw, and start slicing it up the long way.” As the pieces fell away from the log, the idea of creating a shelving unit by finding a simple way to simultaneously separate and connect the layers took shape in his mind. “Each time the log comes off, you have to lift it up, move it, and turn it over. You do this all day and you start to realize that the way the planks are coming off the tree are such a beautiful thing to see. It’s so obvious, so simple and, like a lot of design, you wonder why has no one has done this before.”

However, as once living things, logs do not respond to design challenges the same way many other materials do. “More often than not, you slice into a tree and it just doesn’t work,” Lehrecke points out. “You mill it up, and a lot of things can go wrong. There may be nails or ant colonies inside. There’s a lot of tension in a log when it’s growing, depending upon the conditions under which it’s growing. When they dry, all the tension comes out and it can ruin the logs. You might put a log away in the drying shed and congratulate yourself for having this beautiful piece, and then it checks, which is like a big crack that goes down the center of a log.” But for Lehrecke, this is all a welcome part of the process. When a log doesn’t work for one project, he tries to find another use for it. “Maybe you have to cut it up and use it for legs. We try to roll with the punches and use every part of the tree for something. This is the fun part,” he says, “where you just say, maybe I’ll do a line of chairs this fall or use all the scraps for lamp bases.”

|

180 DESIGN SECRETS: FURNITURE |

|

|

For the Exploding Log Shelves, Lehrecke gets logs through tree removal services. One of his favorite trees to use is catalpa. “It’s one of most beautiful woods and almost never seen in furniture,” he says. “The grain is very beautiful, very Asian. But there’s not enough of it to create a market and it’s very soft. Most companies want to work with harder, more durable wood. I love making furniture from wood that has no lumberyard or commercial value. There are these logs that are beautiful, but are not straight enough, or there’s just not enough of it around. They have more character even if they’d don’t have enough commercial value.”

For the Exploding Log Shelves, Lehrecke gets logs through tree removal services. One of his favorite trees to use is catalpa. “It’s one of most beautiful woods and almost never seen in furniture,” he says. “The grain is very beautiful, very Asian. But there’s not enough of it to create a market and it’s very soft. Most companies want to work with harder, more durable wood. I love making furniture from wood that has no lumberyard or commercial value. There are these logs that are beautiful, but are not straight enough, or there’s just not enough of it around. They have more character even if they’d don’t have enough commercial value.”

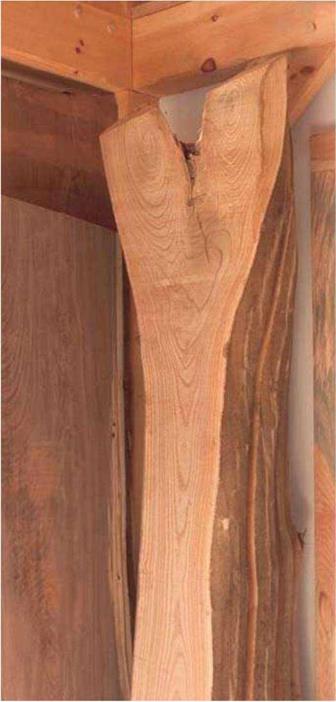

Lehrecke’s prime concern with the Exploding Log Shelves is to preserve as much of the natural character of the tree as possible, while still creating a viable shelving unit. “The design dilemma,” he notes, “was how do you do this with as little interruption as possible. This slight I beam I came up with was the most minimal means of supporting the shelves structurally, without interrupting it visually.”

The supports are made of flat steel stock, about 4" (10 cm) wide x f" (0.6 cm) thick, which are welded to another piece of flat steel that is invisibly morticedmortised into the wood. “When you look at it from the front, you almost don’t see anything,” Lehrecke notes. “That was the idea here. At certain angles, you don’t pick up the metal at all, you just see the shelves suspended apart from one another.”

The shelves are given the most minimal finishing treatments. The steel supports are oxidized with chemicals to make them black. As for the wood, according to Lehrecke, “We have a very simple way of dealing with wood. We find beautiful wood, we sand it to very fine grit, and then put two or three coats of wiping varnish on it, so it has a very minimal finish, but one that’s protecting the piece. We want it to look like wood. We don’t want to make it look like its been sprayed with a high-tech finish.”

As fond as Lehrecke is of his raw materials, he remains pragmatic in his approach. “There are a lot of folks that talk to trees,” he says, “but I’m not one of them. I just love the material. The more I’ve learned about it, the more interesting it becomes. I keep learning about which woods are good for what and what to watch out for in terms of working with them, and how they dry. It’s never boring, and I keep learning things.”

Lehrecke also finds that his eclectic background helps him find new ways to interact with this oldest of materials. “There seem to be two distinct communities of wood,” he says. “One is the craft community, the people who went to woodworking and furnituremaking school, and I didn’t do that. Then there’s the architecture and design-oriented community, and most of them have gone to architecture school and have not done much practical building. I fall somewhere between the two because I have a background in both, but I’m not overly influenced by either.” However, to his neighbors in the countryside of New York State, “I’m the strange guy with the wood stumps. When they see some article in the New York Times, and see what someone paid for one of my pieces, they just laugh when I come into the country store.”

Lehrecke also finds that his eclectic background helps him find new ways to interact with this oldest of materials. “There seem to be two distinct communities of wood,” he says. “One is the craft community, the people who went to woodworking and furnituremaking school, and I didn’t do that. Then there’s the architecture and design-oriented community, and most of them have gone to architecture school and have not done much practical building. I fall somewhere between the two because I have a background in both, but I’m not overly influenced by either.” However, to his neighbors in the countryside of New York State, “I’m the strange guy with the wood stumps. When they see some article in the New York Times, and see what someone paid for one of my pieces, they just laugh when I come into the country store.”

|

Each milled log is stored for two to three years of air drying. Seeing the logs in this form was Lehrecke’s inspiration for the Exploded Log Shelving Unit.

Credit: Dan Howell

|

182 DESIGN SECRETS: FURNITURE |

|

|

|

|