Honda [91] and Fisher [62, 63] also came from a botany background. Their approach is to simulate the branching structures of trees and other plants using another procedural model. Here, for the first time, three-dimensional tree skeletons evolve. The pictures are obtained through projection of the 3D-data onto the viewing plane. However, the model is still constructed relatively simply:

■ Internodes are straight, the thickness is not taken into account. The geometrical data thus only consists of line segments, the only type of element, which at this time was supported by monitors.

■ ![]() Only binary branching occurs. The length of the branched segments (child elements) is correlated to the length of the father segments using two relational values r1 and r2.

Only binary branching occurs. The length of the branched segments (child elements) is correlated to the length of the father segments using two relational values r1 and r2.

■ The father segment and the two child segments are at one level. The child segments have a constant branching angle. The offshoots form an exception, at which divergence is permitted.

■ The branching increases in discrete steps with each branching order, a procedure that also is adopted directly from nature, and which can be observed in most natural tree skeletons.

|

|

|

|

Although it is a simple procedure, with this model realistic-appearing tree skeletons evolve (see Fig. 4.3). Because of their three-dimensionality, these models can be turned arbitrarily on a display screen.

Simultaneously the first realistic-appearing plants were generated using rewriting systems, and for the computer graphics community more modeling aspects emerged. At the same time, however, this also opened up several questions: How efficiently can a concretely defined branching structure be reproduced? What kinds of variations can be generated using only a certain modeling method and what is the needed effort?

Section 4.3

![]() Three-Dimensional Procedural Models

Three-Dimensional Procedural Models

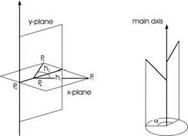

Figure 4.4

Parameters in the model by Aono und Kunii: (a) parameterization of branches; (b) divergence angle

In response to these considerations, Aono and Kunii [5] extended the procedure developed by Honda [91]. Here, special emphasis is given to the modeling of branching. The extended method has the following attributes:

■ Branching occurs through bifurcation, i. e., binary branching, the trees thus modeled have monopodial or sympodial forms.

■ The lengths and diameters of the forked branches decrease with a constant factor; the branching angle remains constant throughout all bifurcation stages.

■ The two forked branches are located in a plane that is spanned by the father branch axis and his maximal gradient.

■ The branching takes place simultaneously at the branch tips.

|

|

|

|

Figure 4.4a shows the parameters of the model. Most elements of this branching model are used in later approaches, though in extended or modified forms. Although the models are relatively fixed, it is possible to produce a number of interesting and also, as statistically proven in [5], realistic-looking branching models. in particular, different kinds of phyllotaxis can be modeled in this way. In Fig. 4.5 we show several examples of branching structures that were generated according to this method.

Aono and Kunii extend their basic model in several aspects. By introducing attractors and inhibitors, they bend the models, thus to simulate the influence of wind (Fig. 4.5c). Other types of branching patterns are introduced and, additionally, the branching angles are modified in accordance with their developing age, such as in Fig. 4.5d.

Chapter 4 The produced branching structures impress in their variety and natural effects.

Procedural Modeling Geometrical aspects are here not of any major importance. So leaves, for ex

ample, are only rudimentarily sketched, and the geometries of the trunk and branches are generated only by line segments of different thickness.

Aono and Kunii were critical of the then popular L-systems, because of their awkwardness and their limitations when handling all the rules that were required to produce their own models. Prusinkiewicz and Lindenmayer proved these objections later as not substantiated [166], in particular by using parametric L-systems for the creation of similar forms of branching.