Chinese style—Sir William Chambers—The Brothers Adams’ work—Pergelesi, Cipriani, and Angelica Rauffmann—Architects of the time—Wedgwood and Flaxman—Chippendale’s Work and his Contemporaries—Chair in the Barbers’ Hall— Lock, Shearer, Hepplewhite, Ince, Mayhew, Sheraton—Introduction of Satinwood and Mahogany—Gillows of Lancaster and London—History of the Sideboard—The Dining Room—Furniture of the time.

oon after the second half of the eighteenth century had set in, during the latter days of the second George, and the early part of his successor’s long reign, there is a distinct change in the design of English decorative furniture.

oon after the second half of the eighteenth century had set in, during the latter days of the second George, and the early part of his successor’s long reign, there is a distinct change in the design of English decorative furniture.

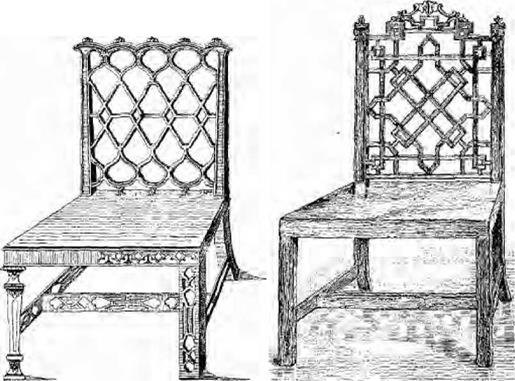

Sir William Chambers, R. A., an architect, who has left us Somerset House as a lasting monument of his talent, appears to have been the first to impart to the interior decoration, of houses what was termed "the Chinese style," after his visit to China, of which a notice was made in the chapter on Eastern furniture: and as he was considered an "oracle of taste" about this time, his influence was very powerful. Chair backs consequently have the peculiar irregular lattice work which is seen in the fretwork of Chinese and Japanese ornaments, and Pagodas, Chinamen and monsters occur in his designs for cabinets. The overmantel which had hitherto been designed with some architectural pretension, now gave way to the larger mirrors which were introduced by the improved manufacture of plate glass: and the chimney piece became lower. During his travels in Italy, Chambers had found some Italian sculptors, and had brought them to England, to carve in marble his designs; they were generally of a free Italian character, with scrolls of foliage and figure ornaments: but being of stone instead of woodwork, would scarcely belong to our subject, save to indicate the change in fashion of the chimney piece, the vicissitudes of which we have already noticed. Chimney pieces were now no longer specially designed by architects, as part of the interior fittings, but were made and sold with the grates, to suit the taste of the purchaser, often quite irrespective of the rooms for which they were intended. It may be said that Dignity gave way to Elegance.

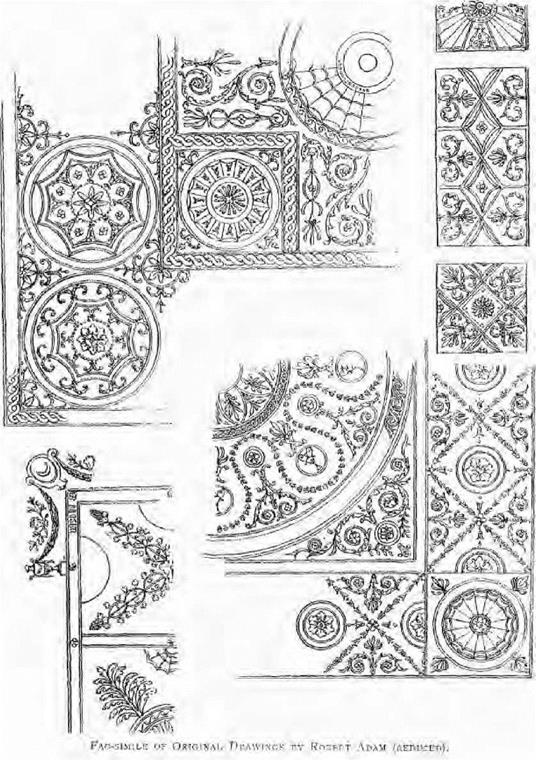

Robert Adam, having returned from his travels in France and Italy, had designed and built, in conjunction with his brother James, Adelphi Terrace about 1769, and subsequently Portland Place, and other streets and houses of a like character; the furniture being made, under the direction of Robert, to suit the interiors. There is much interest attaching to No. 25, Portland Place, because this was the house built, decorated and furnished by Robert Adam for his own residence, and, fortunately, the chief reception rooms remain to shew the style then in vogue. The brothers Adam introduced into England the application of composition ornaments to woodwork. Festoons of drapery, wreaths of flowers caught up with rams’ heads, or of husks tied with a knot of riband, and oval pateroe to mark divisions in a frieze, or to emphasize a break in the design, are ornaments characteristic of what was termed the Adams style.

Robert Adam published between 1778 and 1822 three magnificent volumes, "Works on Architecture." One of these was dedicated to King George III., to whom he was appointed architect. Many of his designs for furniture were carried out by Gillows; there is a good collection of his original drawings in the Soane Museum, Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

The decoration was generally in low relief, with fluted pilasters, and sometimes a rather stiff Renaissance ornament decorating the panel; the effect was neat and chaste, and a distinct change from the rococo style which had preceded it.

The design of furniture was modified to harmonize with such decoration. The sideboard had a straight and not infrequently a serpentine-shaped front, with square tapering legs, and was surmounted by a pair of urn-shaped knife cases, the wood used being almost invariably mahogany, with the inlay generally of plain flutings relieved by fans or oval pateroe in satin wood.

Pergolesi, Cipriani and Angelica Kaufmann had been attracted to England by the promise of lucrative employment, and not only decorated the panels of ceilings and walls which were enriched by Adams’ "oompo’" (in reality a revival of the old Italian gesso work), but also painted the ornamental cabinets, occasional tables, and chairs of the time.

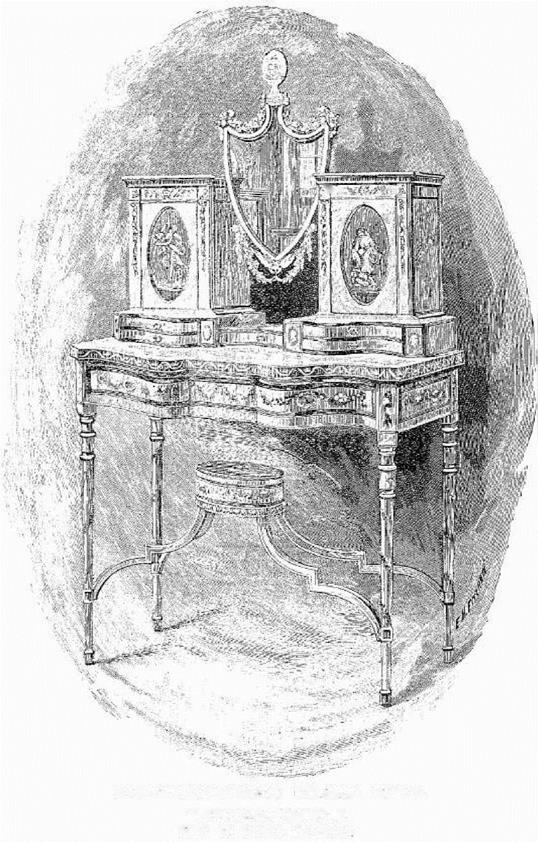

Towards the end of the century, satin wood was introduced into England from the East Indies; it became very fashionable, and was a favourite ground-work for decoration, the medallions of figure subjects, generally of cupids, wood-nymphs, or illustrations of mythological fables on darker coloured wood, formed an effective relief to the yellow satin wood. Sometimes the cabinet, writing table, or spindlelegged occasional piece, was made entirely of this wood, having no other decoration beyond the beautiful marking of carefully chosen veneers; sometimes it was banded with tulipwood or harewood (a name given to sycamore artificially stained), and at other times painted as just described. A very beautiful example of this last named treatment is the dressing table in the South Kensington Museum, which we give as an illustration, and which the authorities should not, in the writer’s opinion, have labelled "Chippendale."

|

|

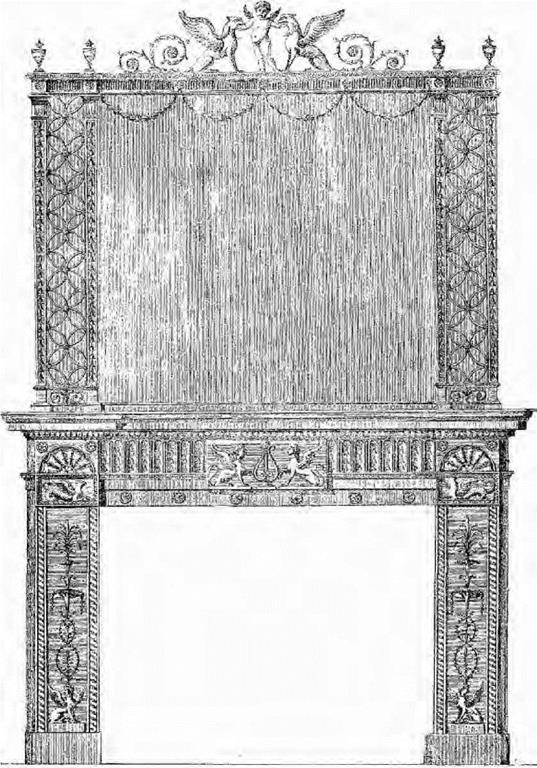

Besides Chambers, there were several other architects who designed furniture about this time who have been almost forgotten. Abraham Swan, some of whose designs for wooden chimney pieces in the quasi-classic style are given, flourished about 1758. John Carter, who published "Specimens of Ancient Sculpture and Painting"; Nicholas Revitt and James Stewart, who jointly published "Antiquities of Athens" in 1762; J. C. Kraft, who designed in the Adams’ style; W. Thomas, M. S.A., and others, have left us many drawings of interior decorations, chiefly chimney pieces and the ornamental architraves of doors, all of them in low relief and of a classical character, as was the fashion towards the end of the eighteenth century.

Josiah Wedgwood, too, turned his attention to the production of plaques in relief, for adaptation to chimney pieces of this character. In a letter written from London to Mr. Bentley, his partner, at the works, he deplores the lack of encouragement in this direction which he received from the architects of his day; he, however, persevered, and by the aid of Flaxman’s inimitable artistic skill as a modeller, made several plaques of his beautiful Jasper ware, which were let in to the friezes of chimney pieces, and also into other wood-work. There can be seen in the South Kensington Museum a pair of pedestals of this period (1770-1790) so ornamented.

It is now necessary to consider the work of a group of English cabinet makers, who not only produced a great deal of excellent furniture, but who also published a large number of designs drawn with extreme care and a considerable degree of artistic skill.

The first of these and the best known was Thomas Chippendale, who appears to have succeeded his father, a chair maker, and to have carried on a large and successful business in St. Martin’s Lane, which was at this time an important Art centre, and close to the newly-founded Royal Academy.

Chippendale published "The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director," not, as stated in the introduction to the catalogue to the South Kensington Museum, in 1769, but some years previously, as is testified by a copy of the "third edition" of the work which is in the writer’s possession and bears date 1762, the first edition having appeared in 1754. The title page of this edition is reproduced in fae simile on page 178.

ENGLISH SATIN WOOD DRESSING TAI3LE.

ENGLISH SATIN WOOD DRESSING TAI3LE.

Wift tainted Decor! uion,

Ек. й of XVIIL Century

|

|

|

|

|

|

CHIMNEYPIECE AND OVERMANTEL.

DKSiGXKD JSY VV. ТномАь. ARCHITECT T7S3.

Very similar to Robert Adam s work.

|

|

This valuable work of reference contains over two hundred copperplate engravings of chairs, sofas, bedsteads, mirror frames, girandoles, torcheres or lamp stands, dressing tables, cabinets, chimney pieces, organs, jardinieres, console tables, brackets, and other useful and decorative articles, of which some examples are given. It will be observed from these, that the designs of Chippendale are very different from those popularly ascribed to him. Indeed, it would appear that this maker has become better known than any other, from the fact of the designs in his book being recently republished in various forms; his popularity has thus been revived, while the names of his contemporaries are forgotten. For the last fifteen or twenty years, therefore, during which time the fashion has obtained of collecting the furniture of a bygone century, almost every cabinet, table, or mirror-frame, presumably of English manufacture, which is slightly removed from the ordinary type of domestic furniture, has been, for want of a better title, called "Chippendale." As a matter of fact, he appears to have adopted from Chambers the fanciful Chinese ornament, and the rococo style of that time, which was superseded some five-and-twenty years later by the quieter and more classic designs of Adam and his contemporaries.