Borrowed scenery is, by Japanese standards, a natural element that forms the background of a picture plane in which the actual garden forms the foreground. In other words, borrowed scenery refers to the intentional incorporation of a distant scenic element—the actual focal point of the garden—against which a garden scene is created in the foreground to complement the greater effect. It is a technique whereby a garden of limited area is set against a feature of a distant natural scene, such as a mountain, to draw a sense of the infinite into a finite environment.

Take the garden of Jiko-in, near Nara, in which a panoramic scene is framed by the eaves and the veranda of the temple. It is composed of a shallow garden of clipped bushes in the foreground, and the Yamato mountains shrouded in mist in the background, across the broad sweep of the Nara Basin. The Jiko-in garden is made limitless by this composition.

“Prospect,” meanwhile, refers to a panoramic vista unobstructed by an artificial framing element—or the type of view, for example, which would be afforded someone standing in the far corner of the foreground garden at Jiko-in, looking out toward the mountains of Yamato. It is as though one has stepped through the picture frame into a landscape painting. This is where we can draw the line—delicate though it may be—between the artifice of a cultivated garden and the beauty of nature, or between viewing nature as part of a composed scene and merely viewing nature.

It is only when the interior of the building and the view of the outside are completely balanced, as they are in architectural forms specifically designed to provide panoramic views, that prospect qualifies as a category of gardening methodology.

The gardener’s art creates a composed picture by capturing the beauty of nature in the frame formed by the building’s eaves or lintels, pillars, and door sill or floor line. What makes it the “art” of gardening is that the human hand has, in some way or another, enhanced nature as it exists.

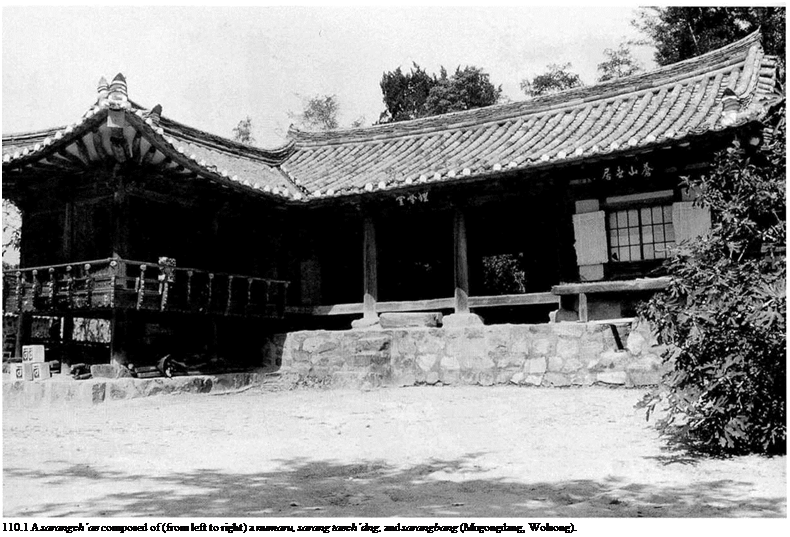

On the whole, the garden-making approach used in traditional Korean residences falls somewhere between “prospect” and “borrowed scenery,” and represents a view of garden making that came into prominence in Korea during the Choson period. The gardens of Choson Korea developed from two traditions: the first is this approach to gardening that lies somewhere between prospect and borrowed scenery, and the second is that handed down from the older kingdoms of Unified Silla and Koryo. The former may be called an introverted approach (not intended for display), and the latter, extroverted. Indeed, the extroverted approach produced highly symbolic garden compositions, such as the Kyonghoeru Pond of Kyongbokkung and the ponds in the outer gardens of yangban estates. The introverted approach, on the other

hand, is characteristic of the Choson period, and closely related to everyday household activities. However, the introverted approach also includes another garden form—the creation in Korea of environments for the pydlso (retreats) of Confucian scholars—which are very similar in their ideological background to Chinese yuanlin.