Garden ownership reached its height during the Tang and Song dynasties. It was during this same period that scholars and painters appeared in great numbers, leading to the emergence of free-form landscape-style gardens that were supported by literature and landscape painting. The Song dynasty in particular has been called the golden age of the arts, including gardens.

A well-known literary work of the late Northern Song dynasty by Li Ge-fei, Luo-yang ming-yuanji (“The Famous Gardens of Louyang”) describes eighteen famous gardens of the time, citing the following as the ideals on which they were designed:

There are six attributes that do not combine in fine scenery: where magnificence is at work, the subtle and profound is lacking; where artificiality prevails, the patina of age is insufficient; where wooded, watery gardens are featured, panoramas are limited. The only garden combining these six elements is Hu yuan.

As this passage suggests, the successful harmonization of antithetical elements of natural and man-made beauty is an ideal in the design of Chinese landscape-style gardens.

Although none of these gardens survive today, vestiges of their forms are still visible in certain scenes of the gardens attached to the Imperial Palace in Beijing, Bei-hai yuan, Yi-he yuan (known to many as the Summer Palace), and Hangzhou’s West Lake.

Private Yuanlin

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, economic development spurred the development of yuanlin in the cities, where the aristocracy, government functionaries, landlords, and nouveau riche merchants were concentrated,

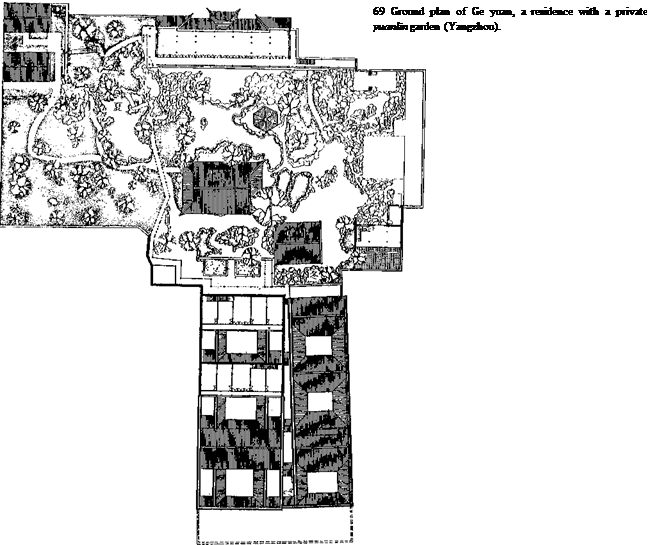

particularly in those cities blessed with a temperate climate and plentiful water supply. Famous gardens of this period still in existence today are concentrated in the Jiangnan region, mainly in Suzhou (including Liu yuan, or “Garden to Linger In”; Wang-shi yuan, “Garden of the Master of the Fishing Nets”; and Zhuo-zheng yuan, “Garden of the Unsuccessful Politician”), and in Yangzhou (for example, Shou xi hu, “Slender West Lake”; He yuan, “He Family Garden”; and Ge yuan, “Isolated Garden”; Figure 69). The main distinguishing feature of private yuanlin is that they are urban gardens that are a condensed interpretation of the prototype of the spacious gardens of the Tang and Song dynasties. This process of modeling and adaptation led to the development of distinctively Chinese techniques of garden making. The development of the yuanlin s progress toward the status of a symbol of the elite—completely divorced from the courtyards within the everyday living quarters—may be

seen as inevitable in light of the historical circumstances surrounding the formation of Chinese gardens, the influence of social stratification, and the compositional style of traditional Chinese residential architecture.