The Japanese stroll garden is a thematically-based series of small garden spaces centered around a pond. It is structured in such a way that as the visitor walks through it, the scenery flows by, with scenes appearing and disappearing sequentially through the use of the compositional technique known in Japanese as miegakure.

The Chinese yuanlin is also a stroll garden, in which the visitor enjoys different scenes and views while sauntering from the central huating to hall, tower, belvedere, and pavilion. Like the Japanese stroll garden, it is composed in the natural landscape-style.

However, as is indicated in the expression bu-yi jing-yi (“changing step, changing view”), qualitatively different scenes emerge one by one as the visitor walks, and thus dynamic, contrasting moods and vistas are fundamental means of expression in the Chinese stroll garden.

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

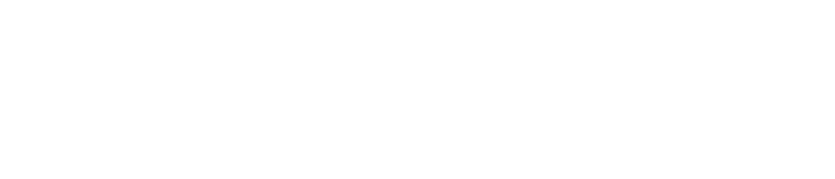

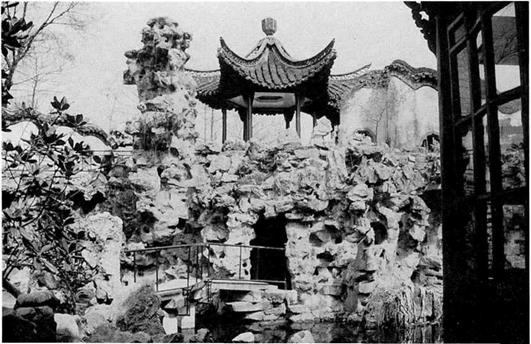

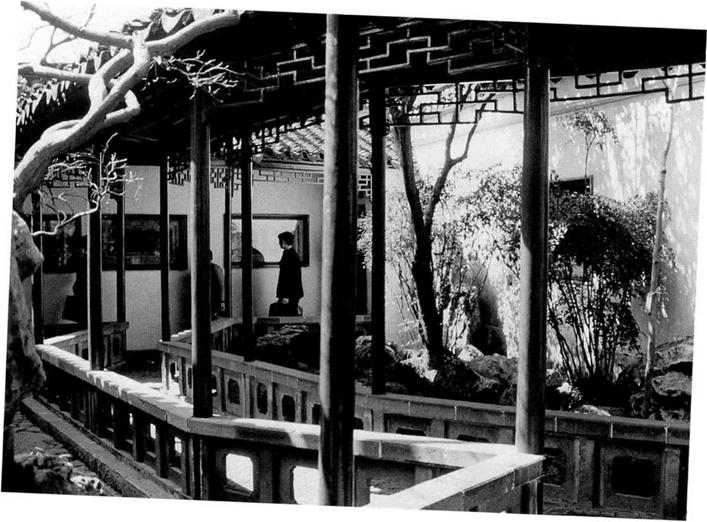

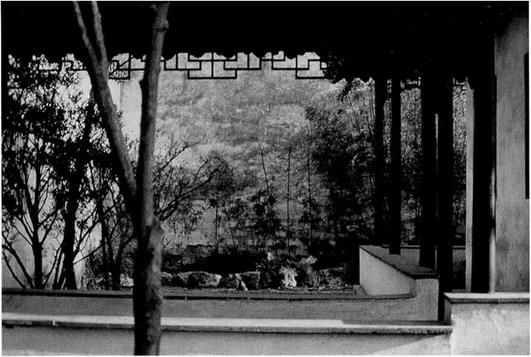

“Screening” and “winding” techniques involving the use of buildings, wall surfaces, fences, caves, gates, and covered walkways divide the entire garden space to create a number of distinct, scenic space cells (Figures 73.1-73.2). Large expanses of water are also converted into a variety of different water features with this method. While these scenes are each different in character, they are also complimentary, and linked into a single environment.

No scene is completely independent of others; each is partitioned and also linked by architectural features—primarily walkways and latticework windows, articulated to prevent oversimplicity or crudeness. This is in direct con

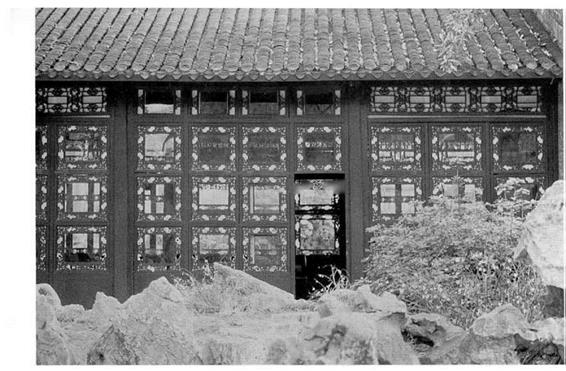

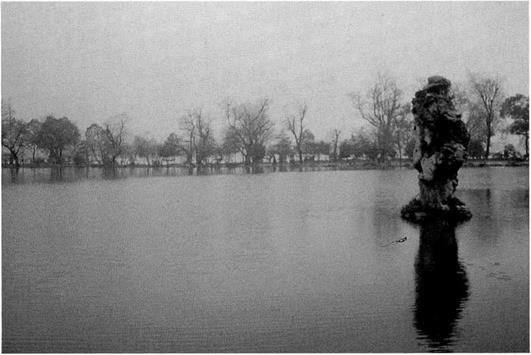

trast to the Japanese miegakure technique effected mainly with natural elements such as plants. Separate scenes in the Chinese garden are not equal in size; rather the main scenes, forming the core of the garden, cover a larger area and are supported by many smaller scenes providing the necessary opposition. The layout of large and small areas is composed with rhythmical changes juxtaposing expansiveness and concentration. These techniques give rise to expressions such as yuan zhongyou yuan (“garden within a garden”), and hu zhong you hu (“lake within a lake”) (Figures 74.1-74.2).

These garden forms, in other words, are an extension

of the idea of bieyou dong tian, or another world (i. e., the paradise of the Taoist Immortals). Chinese yuanlin are composed with ever-changing variety and contrast through the use of garden composition techniques known as yuan bi ge (“gardens must have screens”) and shui bi qu (“water must curve”). The smoother narrative of the Japanese stroll garden can be compared to an “analog” form of expression, in which case the change and opposition marking distinct scenes in the Chinese yuanlin would be “digital.”

Xie-qu yuan (Garden of Harmonious Interest) in the Yi-he yuan (Garden of Cultured Peace) in Beijing is well known as an example of a “garden within a garden,” while the Hua-gang guan-yu (Flower Harbor for Viewing Fish) of Xi hu (West Lake) in Hangzhou is a famous “lake within a lake.”