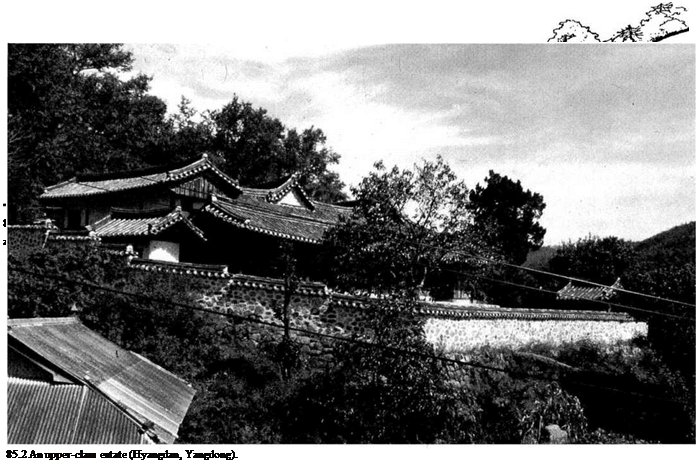

The village of Yangdong in the Wolsong district, about four kilometers (2.5 miles) south of Kyongju, is a treasure trove of traditional rural dwellings. Farmers’ homes are scattered among low pine trees on the southern side of a medium-sized hill. Looming over all, near the summit of the hill and surrounded by a wall, is a particularly impressive estate, which is home to a yangban (civil or military official).

In order to clarify the importance of social status in the composition of traditional Korean homes and gardens, it is necessary here to examine the class system that set the yangban above all their neighbors, as well as the relationship of that class system to the Confucian ideas that served to maintain order in traditional Korean society.

The Centralized Feudal System

Choson, as the kingdom was called, was a highly centralized feudal state, in which noble families and Buddhist temples were forbidden to own large parcels of land. Instead, agricultural land was distributed under a unique system codified in the kwanjonpop (rank land) law.

This law decreed that all land belonged to the state and was to be meted out to individual farming families by

government officials. Title to the land was hereditary, but it was also subject to an inheritance tax. The relationship between landlord and tenant was also governed by this law, which stipulated, for example, that landlords were prohibited from taking land back from a tenant. The government officials responsible for this system’s implementation were the yangban, who formed a privileged class and were paid for their official duties with land and the power to levy taxes.

Adherence to this strict hierarchical social order enabled the Choson dynasty to prevent the development of a powerful land-owning aristocracy and to maintain its own direct control over ordinary farming people. There were five broad social classes in Choson, of which yangban were the highest:

Yangban—Scholar/civil officials, military officials (whose status was lower than that of scholar/civil officials), and the descendents of each. In principle, members of yangban

families were expected to marry within their own class.

Chungin—Skilled professionals, such as lawyers, doctors, and accountants, including low-level government officials.

Sangmin—Traders, artisans, farming families that tilled the fields administered by the yangban, and others. These were the common people, who made up the vast majority of the population.

Nobi—Slaves of the state administration and slaves of wealthier families. (At the beginning of the Choson dynasty, since slavery was hereditary, nearly half the population was slaves.)

Ch’dnmin—Buddhist monks, actors, dancers, musicians, young men with no particular occupation, and other groups generally held in contempt by members of the other four classes.

In most cases, it might seem that the only way to control a nation of small farmers who enjoy a high degree of independence in the running of their farms would be to rely on military strength, which would then lead to the creation of a decentralized feudalism. The Choson dynasty, however, had good reason to maintain a highly centralized feudal system, in the ever-present dual threats of foreign invasion and of interference from the powerful Ming dynasty in neighboring China. Had the Choson dynasty resorted to a decentralized form of feudalism based on military power, it is extremely likely that this would have provoked the intervention of China or some other powerful neighbor.

While it did concentrate power in relatively few hands, centralized land administration by the yangban also provided the machinery for the control of the farming population.

The Introduction of Neo-Confucianism

Neo-Confucianism was a philosophy based on the concept of moral duty. It decreed that each person, from the king down to the lowliest servant, must observe the moral principles appropriate to his or her social class. This philosophy served as the intellectual foundation for the continuation of the class system that gave the yangban their authority. Thus, neo-Confucianism, with its emphasis on duty, took on the status of a state religion, and Buddhism was harshly suppressed. Buddhist monks were outcasts relegated to the lowest rung of society—called the ch’dnmin—and the precepts of neo-Confucianism came to be accepted by the entire population, including Buddhist monks.

From the yangban s point of view, the common people were not only responsible for the maintenance of production, they were also pupils to be tutored in the principles of neo-Confucianism. Moral duty, as stipulated by this belief system, dictated which virtues were appropriate to each class, to the common people as well as to their rulers. It demanded that individuals must submit to authority, and that family loyalty, with its emphasis on respect for one’s ancestors, should be sacrosanct. Under this system, a complex code of etiquette, including rituals of mourning the dead and various ceremonies that enhanced the authority of the elders and helped to preserve order in the villages, was conscientiously observed.

The importance of family names in modern Korea and the chokbo (genealogy book) that people consult before deciding upon a marriage partner are just two examples of how this tradition of maintaining distinct social classes lives on today.

Thus the prevalence of neo-Confucian ideas of moral duty provided a basis and support for the social class system and for the strict system of regulations governing the size of the parcels of land and the homes that each class was permitted to have. These detailed regulations even extended to what kind of rooms a dwelling was to have, and how they were to be decorated.

The village of Yangdong provides a perfect example of the ubiquity of symbols of social status as they are represented in architecture.