The stroll garden, or kaiyiishiki-teien, emerged amid the stable milieu of the Tokugawa regime and its strict social hierarchy with nobles and feudal lords near the top, and urban merchants near the bottom. The spacious gardens built on the private properties of feudal lords are what is usually referred to as “stroll gardens,” but in fact another type of “garden” from this same period can also reasonably be considered a stroll garden—the Pure Land temple garden precincts which became immensely popular as

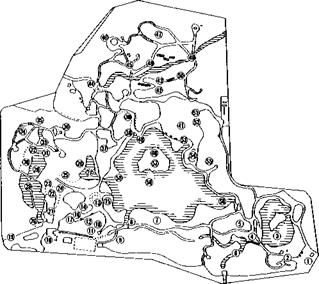

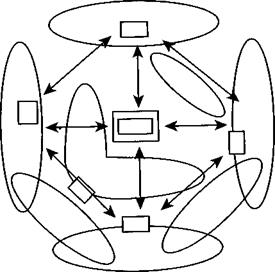

45.1 Plan of Koishikawa Korakuen indicating

sub-garden themes, Tokyo.

@ Little Lushan (China).

@ Togetsu-куб (Kyoto).

@ West Lake dike (China).

© Oi River (Kyoto).

© Tsuten-kyo (Kyoto).

© Chikubu shima (Shiga Prefecture).

recreation grounds with commoners. Thus two fundamentally very similar “garden” styles arose at the same time to serve the needs of two social classes separated by a great social chasm.

Pleasure Gardens of the Dainty6 Feudal Lords

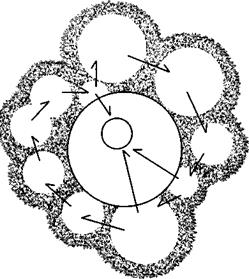

The Tokugawa period saw a tremendous rise in popular interest in travel and faraway places, partly because of the general social stability and perhaps also as a result of the government’s strict restrictions on travel. In a demonstration of their wealth and station, daimyd began to build on their spacious properties huge entertainment-oriented “theme” parks that offered visitors a much sought-after opportunity to “travel.” The parklike stroll garden is composed of numerous sub-gardens based on themes of famous locales in Japan and abroad, and well-known settings for classical and contemporary literary works, all arranged around a pond. Just as the distinctly different spaces of the shoin, sukiya, and soan were “toured,” guests meander along the stroll garden path to tour the qualitatively different garden spaces, and are afforded different views of the pond from strategic points (see Figure 47.2). In most cases, the series of sub-gardens was configured so that people could observe the pond on their right while moving in a clockwise direction around the gardens; this orientation was selected on the basis of simple observation of people’s walking habits.

Although the pond is the center of the landscape composition, no view of the pond in its entirety is ever provided. The interpretations expressed in the stroll garden offer a variety of interesting experiences—being drawn deep

|

|

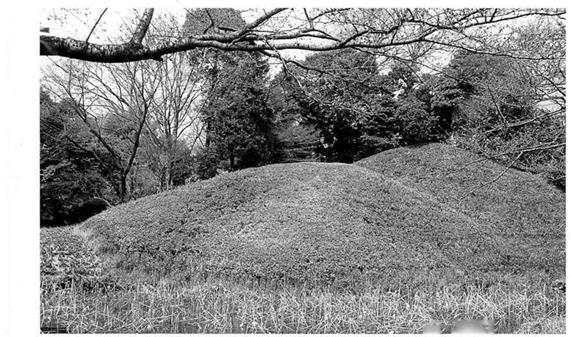

into the mountains and getting an occasional glimpse of the pond through the trees, descending into a valley, crossing an expanse of lawn that resembles a meadow, and looking out over the pond from a nearby tearoom. As guests proceed along the path, views that are always partially obscured appear and disappear in turn, piquing the viewer’s curiosity about the scene to come. The owner’s favorite “famous places of scenic beauty” unfold one after another in a kind of narrative with its own continuity, driven by miegakure (Figures 45.1-45.5).

The compositional techniques used to create these effects are clearly an extension of Sakuteikfs ideas on “offsetting, alternating, [and] overlapping.” The basic difference here, however, is that they are not fixed barriers viewed from a fixed position, but a form of view obstruction based on a moving vantage point that evolves with the walker’s progressive movement through the environment. Stroll garden interpretations involve garden-making methods with a new kind of depth. Miegakure gained in complexity, amid increased concern for and attention to detail in creating garden paths, and was recognized as an effective method for linking distinct gardens.

The prototype of the stroll garden is unmistakably still the “natural landscape.” As mentioned earlier, Edo-period gardens of feudal lords were always based on specific themes—the most popular being well-known scenic locales in Japan and China—which has its basis in Sakuteikis injunctions to use one’s “memories of how nature presented itself for each feature” and to “think over the famous places of scenic beauty throughout the land.”

These gardens are pleasure gardens. The stable social

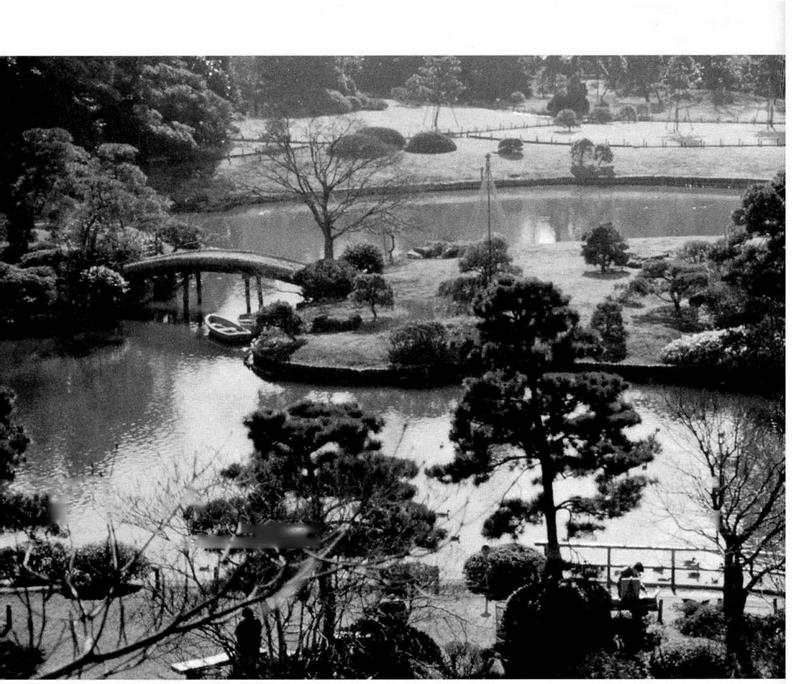

45.2 View of the pond from Fujiyori promontory at Rikugien, Tokyo.

system and peace afforded by a policy of national seclusion provided a sense of liberation from the sublime but severe aesthetics of the medieval period, in which beauty had been confined within extremely strict spatial, formal, and spiritual limits, and allowed an age of the aesthetics of play to blossom.

Pleasure gardens are free of the tension that characterizes Muromachi-period Zen temple gardens, and of the emphasis on status and propriety that was so prominent in shoin gardens. Decidedly sensuous, optimistic, and in accord with the injunction to “think over the famous places of scenic beauty throughout the land,” they are an animated collection of popular themes. These eminently social gardens were created solely as a form of entertainment.

Pleasure “Gardens” of the Urban Merchant Class

Stroll gardens were made by and for feudal lords and wealthy individuals. Originally, the stepping-stones in these gardens were laid in a single row, which restricted walking to single file and thus formed a path reflective of Japan’s hierarchical social order. It has been said that in Japan there has never been a traditional garden style that allowed people to walk two or three abreast, or in larger groups. The exception to this rule, however, can be found in the line of gardens that extend from the Heian-period Pure Land gardens, the temple and shrine precincts that became the grounds for recreation of the urban merchants, or chdmin, who had no land holdings of their own. During the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, the religious pilgrimage—

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

which was exempt from the government’s strict prohibitions on travel—gained great popularity. Pilgrimages involved making a circuit, sometimes over significant distances, of temples and other sacred grounds, in a set order.

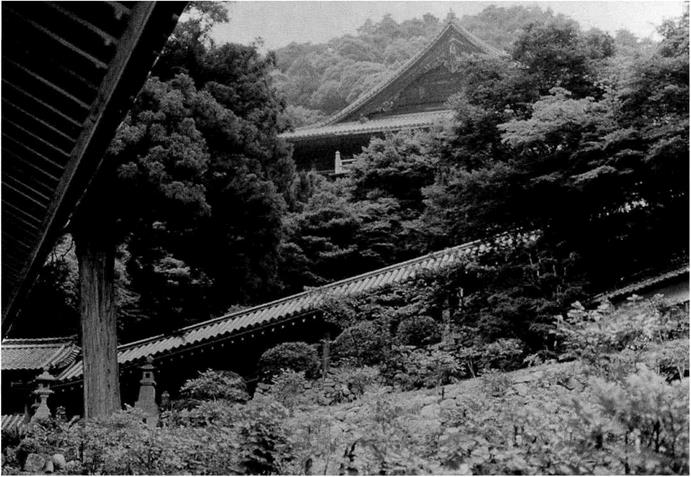

Hasedera, located in the city of Sakurai in Nara Prefecture, is the eighth stop on the pilgrimage circuit of thirty-three Kannon temples in western Japan, and even today is visited by a constant stream of pilgrims.

There are three points that command a full view of the temple: the main gate, the monk’s quarters, and the stage of the main hall. Compositionally these are similar to the views of the pond in the stroll garden. The roofed corridor by which pilgrims gradually ascend to the main hall is flanked by a thick border of peonies which changes—first to azaleas and then to hydrangeas—with each turn of the path. Because of this variety, flowers bloom at the temple year-round. The impressiveness of the view from the front gate gives way to a sense of mystery produced by the inability to make out the full form of the massive elevenheaded Kannon, the primary attendant of the Amida Buddha housed inside the dimly-lit main hall.

Upon turning to leave, the viewer is afforded a magnificent view, from the main hall’s raised platform structure, of the Yamato mountain range glistening in the distance—“Western Paradise”—which creates a wonderful contrasting composition.

While Heian-period Pure Land villa-temple gardens were a static, frontal, unidirectionally-composed staging of Western Paradise at the opposite shore of the lotus pond, Hasedera’s precincts are composed of a number of qualitatively distinct scenes linked by miegakure, which together with the colorful wall of flowers and the incessant chanting of pilgrims produce a highly dramatic and dynamic representation of Western Paradise. Structurally, the “touring” of the temple precincts is the same as the stroll garden’s linking of theme-based garden areas. The “ninety-nine-turn” corridor (kaird) is quintessential miegakure (Figure 46.1).

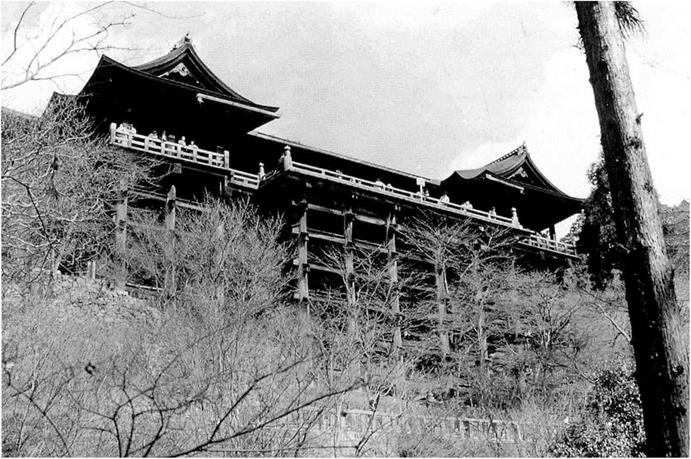

This kind of miegakure landscape composition is seen not only at Hasedera, but also at the Kiyomizudera Kannon in Kyoto (Figure 46.2), the Chiba Kasamori Kannon, the Yanaizu Kokuzo, and other temples. For the most part, temples dedicated to Kannon share this style of composition. Just as the tea of Zen practice became the tea of pleasure, the garden of Zen practice gave way to the pleasure garden. Similarly, just as Heian-period Pure Land villa – temple gardens had expressed faith in salvation by rendering Western Paradise on earth, temple and shrine precincts became the grounds for the recreation of the urban merchant classes—their “gardens” or “parks.”

The people of Edo (present-day Tokyo) were known for both their passionate love of flowers and the beautiful ornamental cherry trees which they cultivated. Nationwide, Edo was praised as “the city of flowers”—and it was in this spirit that the “gardens” of urban merchants initially arose from a desire to link faith and seasonal flora. Many temple and shrine precincts famous for their plum, cherry, azalea, or wisteria blossoms have become venues for flower viewing—a favorite seasonal pastime in Edo Japan, as it is today.

At the foundation of the landscaping concept behind the stroll garden lay aesthetic ideals which, like those of the colorful “gardens” of the urban merchants, were radically new. Various movements striving to establish a sense of tradition emerged among the different social classes in the Edo period. Prominent among these within the merchant classes of the cities was a blossoming of the aesthetics of pleasure variously referred to as iki (urbane chic), okashi – mi (humor; amusement) and/мгум (ostentatious beauty). Both the pleasure gardens of feudal lords and the temple and shrine “gardens” of city merchants show these new aesthetic ideals in full bloom.

|

46.1 View from the main gate of the approach and the main hall of Hasedera, Nara Prefecture. |

|

46.2 View of the main hall of Kiyomizudera, Kyoto. National Treasure. |

|

|

|

|

The basic composition of the temple and shrine precincts as described above is structured in the same way as are the interpretations seen in stroll gardens—not on a linear axis, but by opening and closing views through miegakure. By carefully manipulating the scenes emerging in these intervals, miegakure developed as a methodology that was emotionally charged and free of either spatial limitations or set dimensions. Thus, the stroll gardens devised for the pleasure of feudal lords differed from the temple and shrine “gardens” of city merchants in the way they were perceived by their users, but not in their design interpretations.

The stroll garden shares with sukiya-zukuri gardens like those of Manshu-in and Koho-an a basic dynamic of linking heterogeneous components into a continuous sequence. But while Manshu-in and Koho-an focus on the relationship between buildings and gardens, the emphasis in the stroll garden is on observing scenes—which may include buildings—while meandering through the garden itself. Here the buildings are added as just one of the garden’s compositional elements. Prior to the viewer’s penetration of the garden space, buildings could not usually be seen from the garden. One exception is gardens in the Pure Land style, a classic example of which is Byodo-in at Uji, where the Hoodo hall representing Western Paradise is

viewed from the opposite shore of the pond it borders. In “walking” gardens—roji, stroll gardens, and the precincts of certain shrines and temples—buildings serve as an element in the landscape. Thus determining appropriate and harmonious forms and locations for them becomes a new requirement in garden composition.

By contrast, the intrinsic importance of buildings to garden scenes is at the very core of European and Chinese garden design. Since Chinese gardens are natural landscape-style gardens, they have many elements in common with the Japanese stroll garden; for instance, both are dotted with pavilions, ponds, and islands. However, the differences between them outweigh the similarities. In the composition of Chinese gardens, the focus is on the arrangement of the buildings. The central element in the Chinese garden is the huating open pavilion, which is often open on four sides. Chinese garden makers were required to provide views from and of the huating from many different directions and vantage points.

The Japanese stroll garden emphasizes a multifaceted composition of natural scenes with a pond at the center and regards buildings as simply one more venue for the application of miegakure. The entire formative process of the Japanese garden is synthesized in the stroll garden.