T he clothespress and chest made by John Selden raise some interesting questions regarding patronage patterns in colonial T idewater. Were the pieces purchased in Norfolk during 1775, or could they have been saved from the fire and taken to Blandford, where they were then sold to the Carters? Is it possible that Selden attempted to peddle his surviving cabinetwork on his move to Petersburg? T hese questions are difficult to answer. The only known document associated with Selden’s cabinetwork indicates that he may have had as wide a patronage as the major Williamsburg artisans: in September of 1776 he sold the state a large quantity of furniture for

the Governor’s Palace, then occupied by Patrick Henry, and charged the sum of £91. He was the only cabinetmaker outside of Williamsburg known to have provided furnishings for the Palace.3

![]()

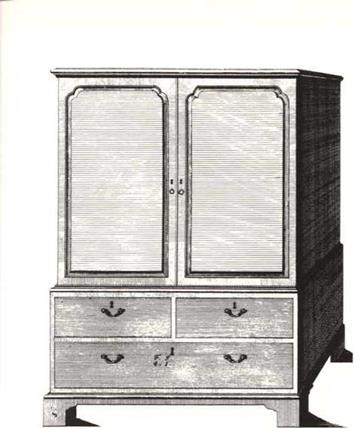

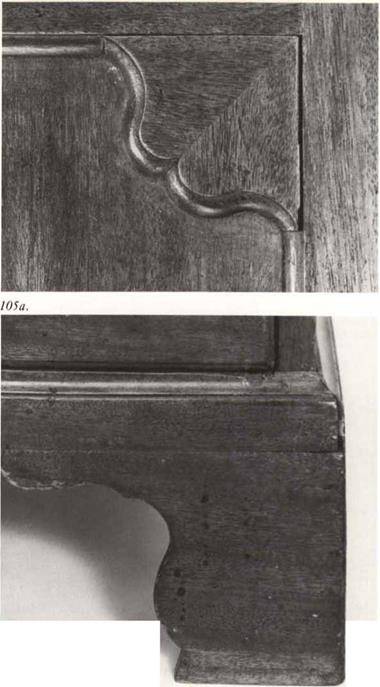

These Selden pieces provide important information on Norfolk production and point out a major problem of its separation from Williamsburg. The clothespress has a paneled back, a detachable cornice, and composite feet, all features seen in case pieces made in Williamsburg. The bottom of the drawers on the clothespress and its accompanying chest are nailed into rabbets and are covered on the edges by continuous strips mitered at the corners— characteristics that are also common in Williamsburg examples. It is important to note as well that the press bears a very close relationship to plate CXXIX of Chippendale’s Director (fig. 105c) and as such is related to other forms and details from this design book that found employment in Williamsburg shops. Nonetheless, these pieces do vary in style from the Chippendale designs, and certain constructional features on the case interiors prove to be helpful in distinguishing Norfolk production.

These Selden pieces provide important information on Norfolk production and point out a major problem of its separation from Williamsburg. The clothespress has a paneled back, a detachable cornice, and composite feet, all features seen in case pieces made in Williamsburg. The bottom of the drawers on the clothespress and its accompanying chest are nailed into rabbets and are covered on the edges by continuous strips mitered at the corners— characteristics that are also common in Williamsburg examples. It is important to note as well that the press bears a very close relationship to plate CXXIX of Chippendale’s Director (fig. 105c) and as such is related to other forms and details from this design book that found employment in Williamsburg shops. Nonetheless, these pieces do vary in style from the Chippendale designs, and certain constructional features on the case interiors prove to be helpful in distinguishing Norfolk production.

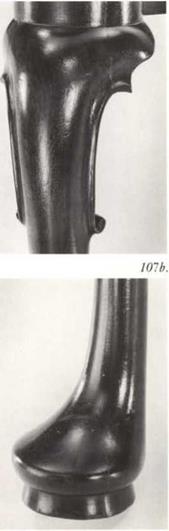

The most notable variation in Norfolk pieces is found in the design of the feet (fig. l()5b). These differ significantly from the straight bracket feet of the Director illustrations, and they have a similar but less vigorous outline than ogee brackets found on Scott pieces (figs. 36, 40, 42). The Selden examples flare severely inward at the base (fig. 105b); while Scott’s have this detail, they are not as accentuated. In addition, the coved base molding is unknown in Williamsburg examples. It appears that Selden case pieces may be recognized by these features—a possibility that gains further support when it is realized that the clothespress and chest of drawers w ere not made en suite: the clothespress has a simple quarter-round molding on the edges of the drawers and the chest has an applied cock bead. Another Selden feature that may prove to be a regional characteristic is the exaggerated protrusion of the double ogee spandrels on the doors of the press. It is important that those found on a Williamsburg desk-and-bookcase (fig. 77b) are noticeably softer in profile.

In addition to these artistic variations, one significant constructional detail helps differentiate Norfolk case furniture from that of W illiamsburg: the drawer blades are very thin and are backed by three-quarter depth full-bottom dustboards. Occasionally Williamsburg pieces have full-bottom dustboards that fall slightly short of the back, but the separation found on these two Selden pieces is far greater, ranging from one-half to three-quarters of the full case depth.

|

|

105с. “Cloatbs Press”, Plate 129, Thomas Chippendale’s Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director,

third edition 1762 /06. Chest of Drawers, signed "John Selden," Norfolk,

circa 1775.

Mahogany primary; yellow pine secondary.

Height 22 Zi", width 26 %", depth 20%".

Mr. and Mrs. C. Hill Carter, Jr.

|

|

With features that distinguish these Norfolk case pieces thus isolated, it is now possible to examine several other forms that may reflect production there.

A fine card table with a history of ownership in Norfolk could well have been made in that city (fig. 107). Like other furniture from eastern Virginia its form is derived from Knglish design, but the piece otherw ise bears little relationship to furniture from recognized centers in Virginia. It has an abundance of oak secondary wood, and it would undoubtedly be classified Knglish were it not for the poplar drawer sides. The C-scrolls of the knees (fig. I()7a) are similar to those of the early Williamsburg group.

which arc of higher quality, but the pad feet are different from any others known to have been made there. I’hc bold design and excellent construction of this table show it to be from a well-developed urban center.

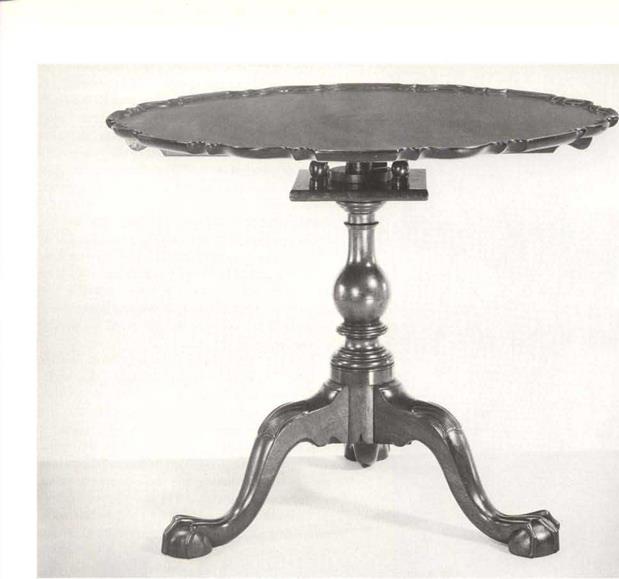

Like the preceding example, a tea table that exhibits excellent workmanship and design may also come from Norfolk (fig. 108). It descended in the Barraud family of Norfolk and Williamsburg and on occasion has been attributed to Philadelphia, although its massive scale is quite unlike examples made there. Several other tables from eastern Virginia exhibit this heavy scale, including one with an unspecified provenance (fig. 121).

|

|

|

|

108. Tea Table, Norfolk (?), circa 1110.

Mahogany.

Height 29Vi", Diameter of top 31".

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (acc. no. 1930-184).

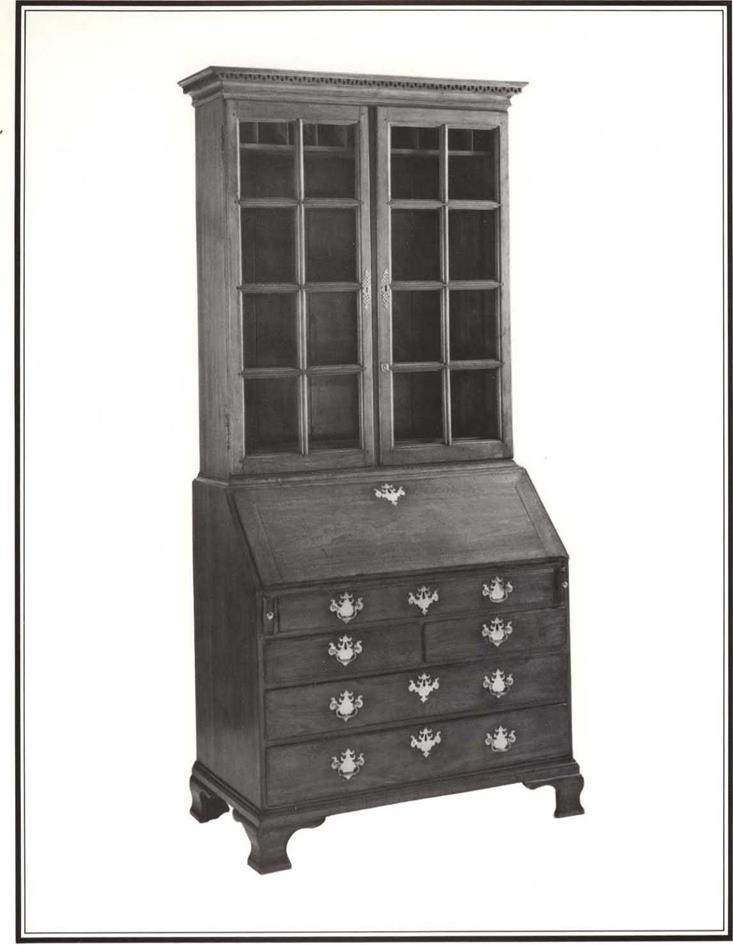

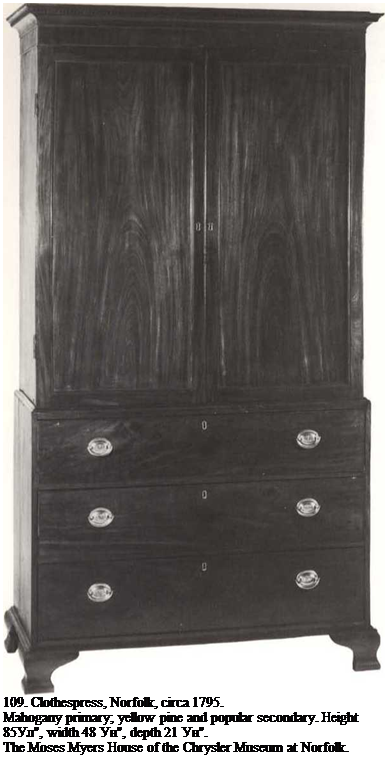

Unlike the colonial period, a large quantity of neo-classic furniture made in Norfolk survives; some of it is exceptionally tine. Such production falls outside the scope of this work, but one clothespress (fig. 109) is included here because it retains earlier features. Made of mahogany with yellow pine and poplar, it descended in the Myers family of Norfolk. The ogee feet, with inward flaring bases and unadorned brackets, are an F. nglish type of the mideighteenth century. A similar example in the Victoria and Albert Museum, signed by David Wright of Lancaster, England, is dated 1751.4 This same foot is utilized throughout southeast Virginia and into northeast North Carolina from the mid eighteenth century well into the nineteenth and probably reflects the dissemination of a Norfolk style in those areas.

Unlike the colonial period, a large quantity of neo-classic furniture made in Norfolk survives; some of it is exceptionally tine. Such production falls outside the scope of this work, but one clothespress (fig. 109) is included here because it retains earlier features. Made of mahogany with yellow pine and poplar, it descended in the Myers family of Norfolk. The ogee feet, with inward flaring bases and unadorned brackets, are an F. nglish type of the mideighteenth century. A similar example in the Victoria and Albert Museum, signed by David Wright of Lancaster, England, is dated 1751.4 This same foot is utilized throughout southeast Virginia and into northeast North Carolina from the mid eighteenth century well into the nineteenth and probably reflects the dissemination of a Norfolk style in those areas.

The w idespread dissemination of Norfolk style comes as no surprise when one considers the migration of Tidewater Virginians into the Albemarle region of northeast North Carolina. Consider, for example, Thomas Sharrock, who served his apprenticeship in Norfolk, moved to Northampton County, North Carolina and proceeded to train at least six of his sons in the cabinetmaking trade.5 A large group of case furniture is attributed to the Sharrock family on the basis of a chest signed by George Sharrock, Thomas’ son, and these have feet related to the Norfolk federal clothespress, as well as those of a desk-and-bookcase from southeast Virginia (fig. 111). It is also of interest that the dustboards of the Sharrock pieces are related to this Virginia desk, as well as to the Selden chest and clothespress. They also have drawer construction corresponding to Selden pieces. The consistency of such features as these, appearing throughout southeast Virginia and northeast North Carolina, points to the influence of Norfolk over a large region.

As the example of W illiamsburg indicates, carved furniture was produced in relatively large quantities in eastern Virginia, so a center as large and active as Norfolk must have made a sizable contribution. Unfortunately, there are no documented carved pieces from that city, and this study can only offer suggestions regarding their identity. One group of carved furniture that may reflect Norfolk production or its influence includes an impressive armchair w ith ball-and-claw feet (fig. 110). One of a pair, it is the most sophisticated example from a large group with histories in 1 Iertford, North Carolina. A number of related objects, including a pair of card tables and a dressing table, come from North Carolina’s Roanoke River Valley, to the west of Hertford and Edcnton.6 All of these have ball-and – claw feet, cabriole legs, and acanthus knee carvings

that arc interrelated. There is some difference in detail and variance in quality, but the overall artistic approach to the elements is unified and is completely different than in Williamsburg. Several dining tables with ball-and-claw feet also relate to this group. These are the six-legged variety that is common throughout southeast Virginia and northeast North Carolina (fig. 102).

In the past, these tables and chairs have been attributed to F. denton, primarily because they have provenances in the surrounding region, but also because they share some similarities to architectural carving found there. The relationship of the furniture with that of the architectural carving is far from convincing, however, since they embody differing techniques anti designs."

|

110. Armchair, Norfolk (?), circa 1160. Mahogany primary; yellow pine secondary. Height 39V*", width 28V*", depth 23V*"’. The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.

|

The suggestion that this group may represent Norfolk cabinetwork is based largely upon circumstantial evidence. An important clue is that they possess a sophistication far superior to a Masonic chair made in the late 1760s for the Halifax, North Carolina Lodge by a local artisan.8 Masonic chairs w ere usually pieces of special commission, committed in every respect to the highest level of artistic achievement in any given region, and they should be a reliable indicator of the prevailing local aw areness of style. Admittedly I lalifax is some distance from F. denton, but the divergence in style between the aw kw ard Masonic chair and the carved Norfolk [?] group is even greater. It is also somew hat difficult to accept the production of an extremely complicated and stylish George II armchair in the small town of F. denton, where architecture and architectural carving show the strong influence of old-fashioned, baroque design.

In conclusion, it appears that Norfolk cabinetmaking had an influence as far w est as Petersburg, and southwest extending well into northeast North Carolina. This is particularly understandable in view of the rural character of the Roanoke River Valley and the isolation of the Albemarle Sound from large ports by the Outer Banks. In an area filled w ith small tow ns, it was necessary for w ealthy and style-conscious patrons to look to Norfolk as the largest and most accessible urban center.

KOOTNOTKS

1. The Virginia Gazette, cd. John Dixon, February 10, 1776, p. 12; population statistics courtesy of Harold B. Gill, Jr., historian, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Williamsburg, Virginia.

2. The Virginia Gazette, cd. Alexander Purdic, July 26, 1776, p. 4.

3. II. R. Mcllwainc, Journal of the Council of the State of Virginia (Richmond: Virginia State Library, ЮЗІ), p. 148. Information courtesy Of I larold B. Gill, Jr.

4. Desmond Fit/.-Gcrald, Georgian Furniture (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1069), entry no. 47.

5. Betty Dahill. "The Sharrock Family, A Newly Discovered School of Cabinetmakers,"Уоагпя/ of Early Southern Decorative Arts 2 (November 1976): 37-51.

6. Frank L. 11 orton, “Carved Furniture of the Albemarle, A Tic w ith Architecture," Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts I (May 1075): 1420.

7. While both of these carvings have punched backgrounds and make use of a bead border in some areas, they have quite different approaches to design and divergent techniques of carving. The facia board and stair brackets from the Blair-Pnllock House have sinuous entw ining vines ending with very small volutes or narrow leaves, and reflect the spirit of baroque design from the late seventeenth century. Many of the leaves and tendrils have busy details formed by gouge cuts, made by driving a gouge at a right angle into the wood. A second cut w as made converging with the first, thereby removing a very small plug. The carsing on the furniture does not utilize the profuse gouge marks and, with the exception of a few veins in each leaf, is characterized by large, plain rounded surfaces. The Icas’cs are much broader and differ completely from the design of those on the architectural elements of the Blair – Pnllock House.

8. Thomas Parramore, launching the Craft: The First Half-Century of Freemasonry in North Carolina (Raleigh: Litho Industries, Inc., 1075), p. 82; files of the Museum of Karly Southern Decorative Arts, Winston – Salem, North Carolina.

|

|