У Y e enter a new era. Are we ready for the changes that are coming? The houses we live in to-morrow will not much resemble the houses we live in to-day. Automobiles, railway trains, theaters, cities, industry itself, are undergoing rapid changes. Likewise, art in all its forms. The forms they presently take will undoubtedly have kinship with the forms we know in the present; but this relationship will be as distinct, and probably as remote, as that between the horseless buggy of yesterday and the present-day motor car.

We live and work under pressure with a tremendous expenditure of energy. We feel that life in our time is more urgent, complex and discordant than life ever was before. That may be so. In the perspective of fifty years hence, the historian will detect in the decade of 1930-1940 a period of tremendous significance. He will see it as a period of criticism, unrest, and dissatisfaction to the point of disillusion — when new aims were being sought and new beginnings were astir. Doubtless he will ponder that, in the midst of a world-wide melancholy owing to an economic depression, a new age dawned with invigorating conceptions and the horizon lifted.

Critics of the age are agreed upon one thought: that what industry has given us, as yet, is not good enough. Another plea of critics hostile to the age is that machines make automatons of men. They fail to see that the machine age is not really here. Although we built the machines, we have not become at ease with them and have not mastered them. Our condition is the result of a swift industrial evolution. If we see the situation clearly, we realize that we have been infatuated with our own mechanical ingenuity. Rapidly multiplying our products, creating and glorifying the gadget, we have been inferior craftsmen, the victims rather than the masters of our ingenuity. In our evolution we have accumulated noise, dirt, glitter, speed, mass production, traffic congestion, and the commonplace by our machine – made ideas. But that is only one side.

We have achieved the beginnings of an expression of our time. We now have some inkling of what to-day’s home, to-day’s theater, to-day’s factory, to-day’s city, should be. We perceive that the person who would use a machine must be imbued with the spirit of the machine and comprehend the nature of his materials. We realize that he is creating the telltale environment that records what man truly is.

It happens that the United States has seized upon more of the fruits of industrialism than any other nation. We have gone farther and more swiftly than any other. To what end? Not the least tendency is the searching and brooding uncertainty, the quest for basic truths which characterize the present day. Never before, in an economic crisis, has there been such an aroused consciousness on the part of the community at large and within industry itself. Complacency has vanished. A new horizon appears. A horizon that will inspire the next phase in the evolution of the age.

We are entering an era which, notably, shall be characterized by design in four specific phases: Design in social structure to insure the organization of

people, work, wealth, leisure. Design in machines that shall improve working conditions by eliminating drudgery. Design in all objects of daily use that shall make them economical, durable, convenient, congenial to every one. Design in the arts, painting, sculpture, music, literature, and architecture, that shall inspire the new era.

The impetus towards design in industrial life to-day must be considered from three viewpoints: the consumer’s, the manufacturer’s, and the artist’s. In his appreciation of the importance of design the artist is somewhat ahead of the consumer, while the average manufacturer is farther behind the consumer than the consumer is behind the artist. The viewpoint of each is rapidly changing, developing, fusing. More than that, the economic situation is stimulating a unanimity of emphasis, a merger of viewpoints.

Until recently artists have been disposed to isolate themselves upon the side of life apart from business; apart from a changing world which, in their opinion, was less sympathetic because its output, in becoming machine-made, was losing its individuality. The few artists who have devoted themselves to industrial design have done so with condescension, regarding it as a surrender to Mammon, a mere source of income to enable them to obtain time for creative work. On the other hand, I was drawn to industry by the great opportunities it offered creatively.

For years I had thought of these possibilities and hesitated only due to the years I had put into the theater. In 1927,1 decided that I would no longer devote myself exclusively to the theater, but would experiment in designing motor cars, ships, factories, railways — sources more vitally akin to life today than the theater. The theater of the present moment is marking time due to the tremendous progress of talking pictures. Many of my friends interpreted my decision as an eccentric gesture and predicted that my new venture would be short-lived. Actually this change represented no violent

[П

jump from the identically sincere principles upon which I had always worked. It was a natural evolution. What amazes me is that more men have not done the same thing.

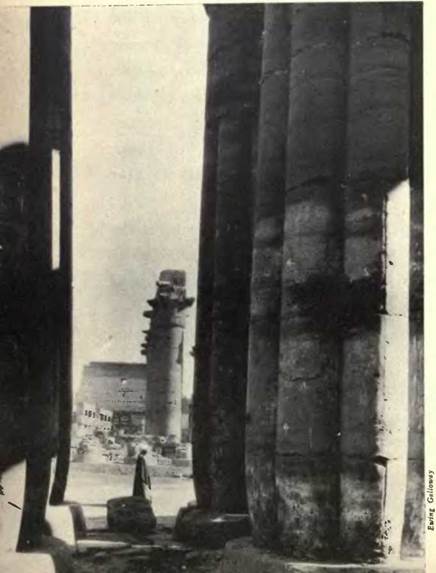

An artist is sensitive to his environment. As you look back and think of Egypt, pl‘“1 of Greece,2 of any of the outstanding eras in the past, you visualize the culture and environment as something to which the artist was susceptible. More than that, he played the important part in creating what you visualize as that era. When working in the theater, it was my endeavor to handle my materials in terms of my own time rather than that of my grandparents. As a matter of fact, I have felt a sense of duty about it. I have felt, and still feel, that it is primarily laziness and a lack of courage on the part і • temple ofamon, luxor designer unknown 1450 в. c. of many of my colleague de

signers in the theater that they fail to do so. In view of this, nothing could be more natural than the step I took. Whether you are sympathetic to the idea or not, industry is the driving force of this age. One of my dearest friends thinks it is the ruination of the age; that We would all be much better if our only possessions were breechcloths and if our homes were a peak in the Himalayas. He may be right. Even that fails to alter conditions that are.

signers in the theater that they fail to do so. In view of this, nothing could be more natural than the step I took. Whether you are sympathetic to the idea or not, industry is the driving force of this age. One of my dearest friends thinks it is the ruination of the age; that We would all be much better if our only possessions were breechcloths and if our homes were a peak in the Himalayas. He may be right. Even that fails to alter conditions that are.

Standards of art are changing as rapidly as standards of wealth and government. Past generations have looked at statues erected on corners and parkways;5 future generations will make monuments of a different caliber.

Due to its stark simplicity, one of the few memorials of the last century that will withstand changes in thought and time is the Washington Monument.41 foresee art being released from its picture frames and prosceniums and pedestals and museums and bursting forth in more inspired forms. I firmly believe that the statue on its pedestal and the painting in its frame will eventually vanish as mediums of expression. Art in the coming generations will have less and less to do with frames, pedestals, museums, books and concert halls and more to do with people and their life.

In the point of view of 2 • PARTHENON DESIGNED BY ICTINUS & CALLICRATES 447 В. С.

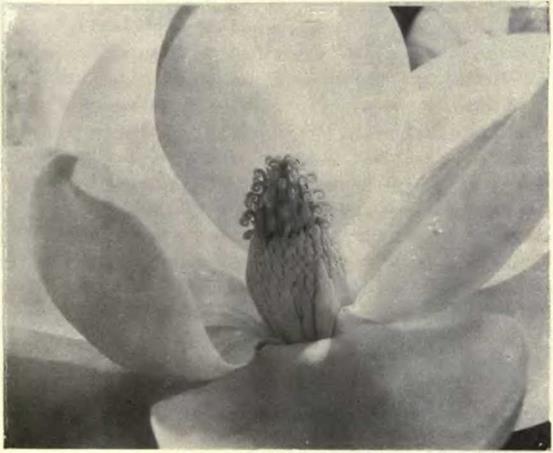

the artist who fails to see an aesthetic appeal in such objects of contemporary life as a railway train,” a suspension bridge,171 a grain elevator,17 a dynamo,14 there is an inconsistency. World that same artist put an apple or a flower in a bowl, make a careful painting of it, and think that he has created a work of art? Is it the subject matter, his technical limitations, or his lack of imagination? Charcoal, paint and clay, to be

the artist who fails to see an aesthetic appeal in such objects of contemporary life as a railway train,” a suspension bridge,171 a grain elevator,17 a dynamo,14 there is an inconsistency. World that same artist put an apple or a flower in a bowl, make a careful painting of it, and think that he has created a work of art? Is it the subject matter, his technical limitations, or his lack of imagination? Charcoal, paint and clay, to be

I sure, are much more sensitive to the I subtleties of individual expression than •< sheet metal, in the same sense that the violin and the piano offer virtuoso possibilities beyond the oboe or trumpet. On the other hand, steamships, airplanes, and radios present the same organic problems in terms of design as do architecture, sculpture, and literature. Keats wrote a few immortal lines about a Grecian urn. Had he known about it and felt like it, he could have written them about an airplane.

Whether or not a man is an artist is determined solely by his work. His private life, the money he earns, his philosophy, his vices, are all beside the point. I know personally most of the serious artists in America and a good number abroad. Regardless of what their mediums are, whether they are painters, sculptors, musicians or poets, they are as much concerned about the money they earn as any average person, including the typical "commercial artist.” However, there is one outstanding difference between them. The commercial artist does what he does with dollars as his inspiration, while the other fellow, the artist, does what he does with the work itself as inspiration. El Greco might have been a magazine illustrator or a bricklayer, but he still would have been a great artist. Cezanne9 at an early stage of his career designed candy – box covers. His widow once very kindly showed them to me in his

[

own house. Gauguin was a banker until he was forty years old.

own house. Gauguin was a banker until he was forty years old.

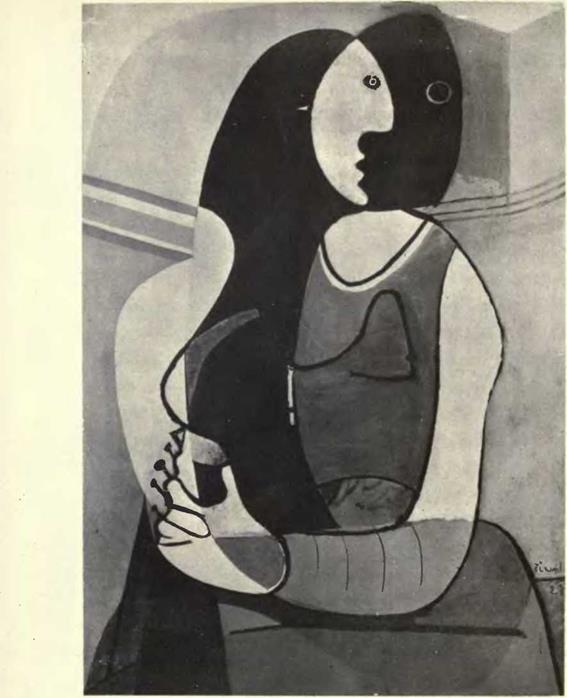

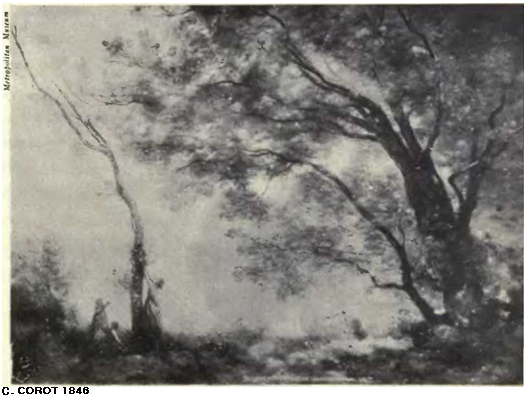

The general public’s idea of artists is derived from the assortment of people who pass by that title. Furthermore the public labors under two handicaps in its judgment of artists. One is that the work of artists is intriguing and mysterious. And any one possessing the barest fundamentals of a technical knowledge on the subject feels himself to be beyond the comprehension of the general public. The other is a belief on the part of most people that they are competent to criticize art, although the same person would be much more modest regarding a scientific problem. In our world of to-day Picasso, an artist, bears the same importance to our life as Einstein, a scientist. In the case of Picasso, the average intelligent person does not understand his work nor does he accept it.’ Einstein is accepted as a matter of course. There is no question in the mind of any one who knows about art that Picasso is one of the greatest painters that has ever lived. The fact that he is forward-looking and experimental gives the same significance to his work as is the case with Einstein. This same general public does not realize that the works of artists whom they now accept*—-as Corot,4 Millet, and Turner — were, in their day, regarded as the works of Picasso are at the present moment. Further than that, they do not know that Picasso has already exerted more influence on the works of future artists than the other three men combined.

There are probably more misconceptions about artists than about any other people. Inspiration is a great asset not only to artists but to any one else. Nevertheless there are many people who think an artist lives on it. I have – one client who on numerous occasions has expressed the keenest disappointment at my never having come into his office unexpectedly and exclaimed wildly about some idea that I got the

Ш

![]() PAINTING BY PABLO PICASSO 1929

PAINTING BY PABLO PICASSO 1929

night before as a result of being inebriated. A grown man, a very successful nationally known business man, he looks upon the artist with the same perplexed admiration that the small boy bestows upon the vaudeville magician.

The work of the artist always has been, and will be, a distinctly individual product — the antithesis of "machine-made.” Fundamentally, the artist is an emotional person in that he relies more upon his feelings and intuitions than upon reasoning. His reaction against the machine, even though it may duplicate a work of his with an exactness beyond his own capabilities and beyond any criticism he can make of it, is an intuitive one. Years ago, when I saw a well-known sculptor using a pneumatic drill to cut away the rough elements from * • souvenir <u mortefontaine painting by jean b.

The work of the artist always has been, and will be, a distinctly individual product — the antithesis of "machine-made.” Fundamentally, the artist is an emotional person in that he relies more upon his feelings and intuitions than upon reasoning. His reaction against the machine, even though it may duplicate a work of his with an exactness beyond his own capabilities and beyond any criticism he can make of it, is an intuitive one. Years ago, when I saw a well-known sculptor using a pneumatic drill to cut away the rough elements from * • souvenir <u mortefontaine painting by jean b.

a statue he was working on, my estimate of him took a sudden drop. I was young and I did not know that to-day’s sculptors use such implements. That he was not chipping away with a mallet and chisel was a disillusion that I failed to get over for a long time. The reaction was instinctive and natural.

During the Renaissance, statues, tombs, and churches were the industry of the times. Michelangelo loved sculpture and detested painting.7 He painte’d

[П]

for purely mercenary reasons. When he decorated the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel he was turning out the great moving-picture epic of his day. The

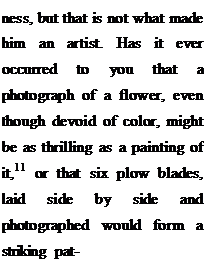

eighteenth-century painter put fruit on a table, made a painstaking copy of it, and in proportion to its realism, it was acclaimed a work of art.*

eighteenth-century painter put fruit on a table, made a painstaking copy of it, and in proportion to its realism, it was acclaimed a work of art.*

Cezanne made his point emphatically and for all time that the subject matter bears no relation to a work of art.* It is this same point of view that has caused to-day’s artist to break from the old standards and caused him to realize that the machines have created problems he alone can solve. Sensitive to color and form, he has begun to see inspiring possibilities in these problems that industry has created but cannot solve without him.

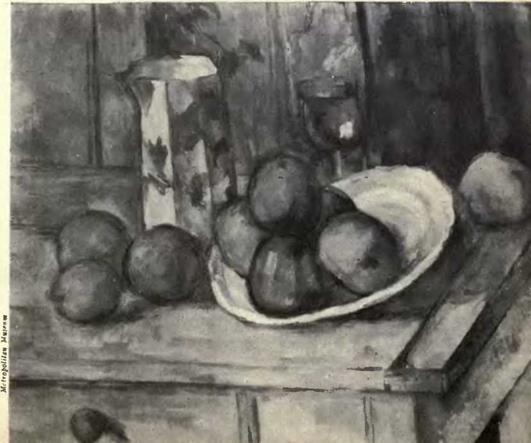

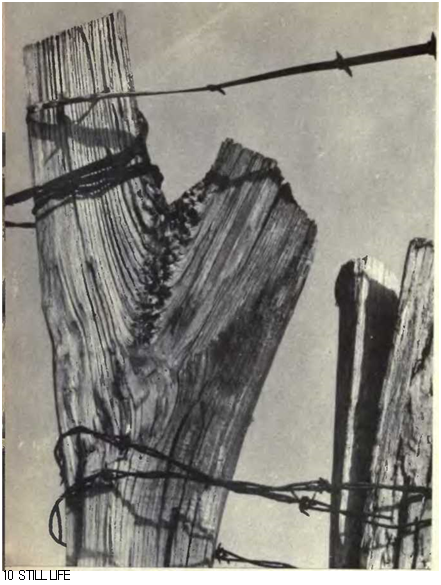

How or by what means an artist expresses himself is of no consequence – It is the vitality and subtlety of feeling which results that gives the work its place in the sun, and it makes no difference whether it was achieved with paint, stone or machine. Camera still life illustrates emphatically that interest in visual form is not the result of subject matter.10 Neither can technical dexterity alone accomplish the result. An artist always, eventually, acquires expert –

8 • STILL LIFE PAINTING BY EM I LI E PREYER 1849

|

tern?12 Or that, in the hands of an artist, eight pairs of spectacles could win your ^esthetic admiration?”

So much for the artist’s viewpoint. Let us consider the consumer. The consumer has seen and read advertisements and has turned trustingly to industry.

But industry, with some conspicuous exceptions, has failed him. It has forced consumers to buy below their taste. Sales organizations have educated the mass to accept 9 ■ still life painting by paul cezanne i895

But industry, with some conspicuous exceptions, has failed him. It has forced consumers to buy below their taste. Sales organizations have educated the mass to accept 9 ■ still life painting by paul cezanne i895

the mediocre as criterion, offering at a reasonable price, not genuine creations, but spurious substitutes of a mongrel-imitation – period type.1” Do not misunderstand me: the in-

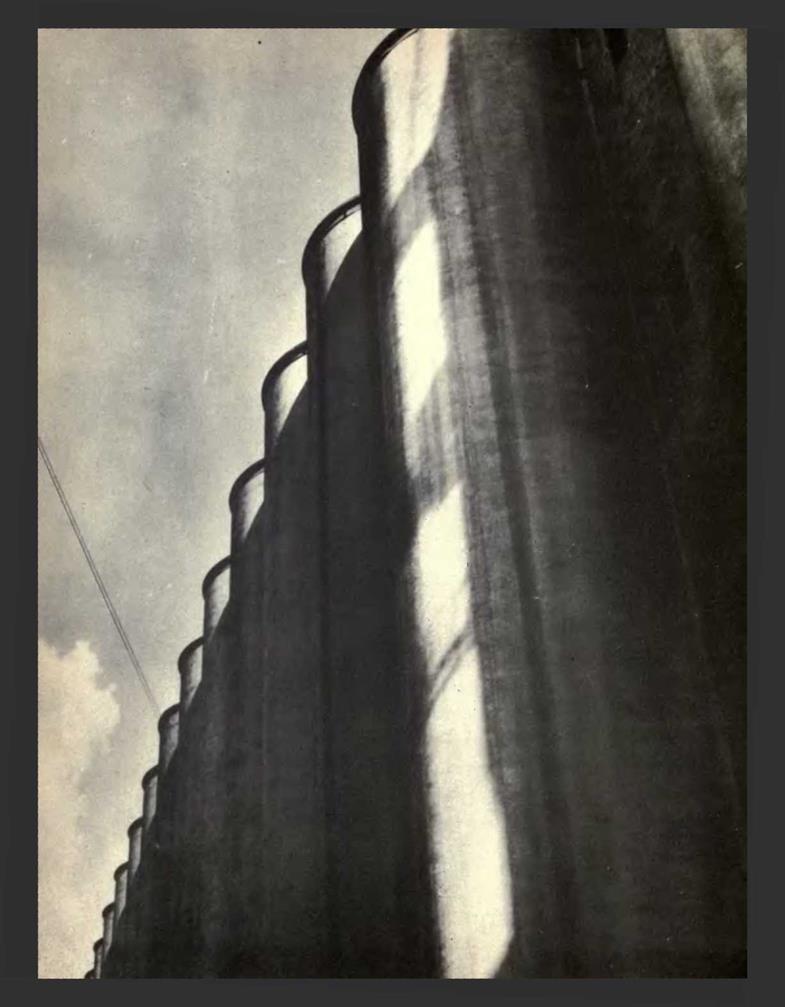

tent of the manufacturers was not this — just their lack of good taste to the point of basing their business on it. Even so and despite all such education, the viewpoint of the mass continues to improve. Some people think of mass action as a thing of our lifetime — of labor unions and the like — forgetting that this country was founded by mass action; forgetting endless historical instances; within our own generation this change probably began with such matters as hours worked per week, and payment per hour, and conveniences and comforts of everyday life such as more " fortunate ” people have. Mass desires to-day photograph by Ralph steiner me go beyond shorter hours. Higher wages are related to aspirations for better living. As a natural result, they are acquiring a taste that is different from that fostered by-the master merchandisers for their consumption. The mass to-day is not interested in mere living but in living the way they would like to live.

Mass production was welcomed as a means of raising the standard of everyday life. In the beginning, it was taken for granted that in cheap machine products satisfactory working results were the most that could be expected. More recently, since mass production has attained new standards of practica-

Mass production was welcomed as a means of raising the standard of everyday life. In the beginning, it was taken for granted that in cheap machine products satisfactory working results were the most that could be expected. More recently, since mass production has attained new standards of practica-

bility, and durability, and cheapness of process, a new attitude on the part of the consumer has made itself felt most emphatically. " Durable and cheap, but look at it!”"’* is the result of an inherent belief that the object which looks good may be expected to have other good qualities!

In what happened several years ago to Mr. Ford’s Model T, the famous and ugly forerunner of his better-looking models of the present day, we have an example of the manner in which consumer demand forced a manufacturer to become aware of the existence of public taste. An attractive car took the place of Model T forced by competition. This competition had long been latent. No competitor could have created it merely as a weapon of trade. It

II ■ STILL LIFE PHOTOGRAPH BY IMOGEN CUNNINGHAM 1925

|

|

[И]

vas a tidal force, the real, though inarticulate demand on the part of the people for quality of appearance. A clinical chart would have shown an improvement in the national blood pressure with the disappearance of Model T!

The average manufacturer, instead of offering the public a straightforward, sincerely designed product, frankly made of whatever material is most suited to its manufacture, frequently distrusts the market. For instance, radio manufacturers feel compelled to produce imitation period furniture."51 There is no justification for not designing a small piece of furniture, such as the radio, at least as simply as the average grand piano ten times its bulk. Manufacturers and merchants, however, insist that they must dress up the radio because of its mechanical aspect — that the public dislikes any suggestion of its functional qualities. Why, then, does not the public object to most of the clocks on the market? Why isn’t the telephone camouflaged to look like a Grecian urn?

This attitude is not true of all manufacturers, of course. There are conspicuous exceptions. In my experience since entering this field I have been tremendously impressed by the enthusiastic interest and response of manufacturers and merchandisers. Their attitude has been, to a great extent, one of surprise that an artist of standing showed any interest in what they were doing; and they have shown both surprise and delight upon finding that it is possible for an artist to work in terms identical with those to which they are accustomed. And now, for reasons that are obvious, we may anticipate that the attitude of the exceptionally far-sighted manufacturer of to-day will be the attitude of the average manufacturer of to-morrow. The successful industrialist with a blind spot for design will presently be a rarity. The facts of the economic situation point in this direction.

Yesterday’s merchandising psychology was to follow in the wake of popular demand and to supply it. To-morrow’s merchandising policy must necessarily be to anticipate public demand and supply it. Since public demand now

is for quality in appearance as well as for quality in service, artists and industry will still further unite their efforts to win the confidence of the public. How, you may ask, will design in the future differ from design in the past? Let me preface my answer to the question by explaining briefly what design means to me.

A design is a mental conception of something to be done. A visual design is the organism of an idea of a visual nature so that it may be executed. It is the practice of organizing various elements to produce a desired result.

A design is a mental conception of something to be done. A visual design is the organism of an idea of a visual nature so that it may be executed. It is the practice of organizing various elements to produce a desired result.

Design deals exclusively with organization and arrangement of form. It is the opposite of accidental. It is deliberate thinking, planning to a purpose.

![]()

![]()

The objective of an industrial designer is not different from the objective of any other designer. A designer is a designer for about the same reasons that a business man (if he is a good one) is a business man: because his major inclinations flow in that direction. His aptitudes, education, experience, knowledge, and desires are an integral part of him, and point to design. No matter what he does, in work or play, in one location or another, he thinks in terms of design. It is natural to him. He is intrigued with the materials of his medium, their advantages and limitations and the possibilities of expression they offer.

The objective of an industrial designer is not different from the objective of any other designer. A designer is a designer for about the same reasons that a business man (if he is a good one) is a business man: because his major inclinations flow in that direction. His aptitudes, education, experience, knowledge, and desires are an integral part of him, and point to design. No matter what he does, in work or play, in one location or another, he thinks in terms of design. It is natural to him. He is intrigued with the materials of his medium, their advantages and limitations and the possibilities of expression they offer.

In order to discuss design, a distinction must

be made between surface qualities and structural qualities. Nevertheless, surface qualities and structural qualities should not be treated separately. The former must be the direct expression of the latter, otherwise there is a lack of sincerity and vitality in the total unit.

Organic surface qualities are the direct expression of the functional requirements of the problem. An unorganic surface treatment is a mere ornamental dress. The Gothic adornment of the Woolworth Building, for instance,

is applied decoration in contrast with the straightforward treatment of the News Building by Raymond Hood. Or, compare Benvenuto Cellini’s famous but despicable design for a cup14 with the cylix of an unknown Greek designer.15

is applied decoration in contrast with the straightforward treatment of the News Building by Raymond Hood. Or, compare Benvenuto Cellini’s famous but despicable design for a cup14 with the cylix of an unknown Greek designer.15

Visual design is concerned with form, space, color; with the proportioning of solids and voids and the rhythmic spac – ings of these elements. The governing factor as to what is pleasing to the eye is the idea, which is of an emotional nature — an emotion of pleasure, satisfaction, excitement, exhilaration, stimulation.

14 • ROSPIGLIOSI CUP. ……

designed by benvenuto cellini 1540 і his reaction vanes with the character

and quality of the idea. Originality and inspiration are two necessary requirements for advanced work in the field of design. They must take root from the conditions and functions of the problem involved. In the Parthenon, for instance, you can find no detail of a superfluous nature.2 This is the result of perfect design.

Our early architects, whom we speak of as “ Colonial,” built their houses,

barns, windmills and furniture with the same spirit and with the same fine quality that appears in the structures of the ancient Greeks. But the Colonials had a distinctly different combination of materials with which to work.” The result they achieved was a sincere, direct expression of the requirements of their problem. Its best examples are simple, honest and fine.

Such perfection is yet to be achieved in our skyscraper form of architecture. In the skyscraper the basic elements are the steel frame and the material enclosing this frame. Until now, this material has been a solid composed of brick or concrete or stone in combination with glass. Ornament, in such forms as decorative cornices, horizontal bands, part of them way up the structure and more along the base, has been considered necessary as a relief to the eye. Architects, having been schooled in materials and principles permitting of such views and consequently believing in them, will tell you that the public would be unhappy if such ornamentation were not employed. Designers of automobiles, who have not been able to free themselves from the precedent of the horseless carriage or coach, take much the same view in their work. How out of place the moldings and gadgets that we see on our automobile, even of the smartest type, would appear if we saw them on an airplane! When the airplane was developed, it was an all new problem. Its requirements were such that it never occurred to any one to base its design principles on, for instance, a carriage with wings.

![]() DESIGNER UNKNOWN 550 В. C.

DESIGNER UNKNOWN 550 В. C.

One may say that when the design of an object is in keeping with the purpose it serves, it appeals to us as having a distinctive kind of beauty. That is why we are impressed by the stirring beauty of airplanes.1’ The underlying principle of the emotional response that the airplane stirs in us would seem to be the same as that which accounts for the emotional effect of the finest architecture — the form, proportion, and color best suited to that object’s purpose. To arrive at the most satisfactory form for any object, the purpose it is to fulfill and the intuition and intelligence of the designer must fuse. The subject makes but slight difference. Of course the designer must study and understand the subject in order to interpret it. He must have a thorough knowledge of the purpose the subject is to fulfill and the simplest means of bringing this about. If he is an artist, as well as a designer, he will accomplish this in a way that will arouse an unusual amount of interest in the onlooker. This latter is the expression of his individuality and it is this particular item that is his greatest asset.

. When Rembrandt painted a model, friend or stranger, the significance of his picture did not depend upon his subject, but upon the painter’s ability to put on his canvas something of the interest he felt in the subject and in such a manner that it creates a profound emotional response in the majority of people looking at it. To-day we do not know that as portraits they were even likenesses — nor do we care. We do know they are works of art. It is much the same with any other form of creative work. When – Wagner composed The Ring he was so absorbed by the emotional excitement of the idea that he put into his music an undefinable rhythmic and melodic combination that stirs any one who hears it. The same can be said of a popular tune, but its span of life is shorter.

The qualities that account for the appeal in experiencing a painting by Manet, a score by Beethoven, the Great Pyramid, Pavlova’s dancing, Shake-

speare’s writing, those qualities which invade the subconscious, stir us deeply, linger in the memory, can only be defined as emotional. The qualities that make one steamship, vase, airplane, or skyscraper appeal to us, while another does not, are of the same nature. When we look at a painting that pleases us, we experience a definite emotional reaction.

It may be subdued or even subconscious.

It may be subdued or even subconscious.

Any one who enjoys Da Vinci’s painting of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre experiences such an emotion. The same is true with reference to Rodin’s Burghers of Calais, or a tale of Poe’s. When we listen to music that we enjoy, it is an emotional experience. When this emotion disappears we begin to be bored.

When viewing a scene which strikes you as beautiful, you experience an emotion.

When you stand on a hill along the Mo – nongahela River, looking out over miles of steel mills, hundreds of stacks belching flame, you are experiencing an emotion. You may have had the same experience in a chateau in France, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, on the rim of the Grand Canyon, or when looking at a piece of furniture, or even at a fragile wineglass. Likewise, if the sight of the Akron or of Man o’ War leading the field down the home stretch excites you, you are reacting to an emotion. When automobiles, railway cars,

|

|

airships, steamships or other objects of an industrial nature stimulate you in the same way that you are stimulated when you look at the Parthenon, at the windows of Chartres, at the Moses of Michelangelo, or at the frescos of Giotto, you will then have every right to speak of them as works of art.

Just as surely as the artists of the fourteenth century are remembered by their cathedrals, so will those of the twentieth be remembered for their factories and the products of these factories.