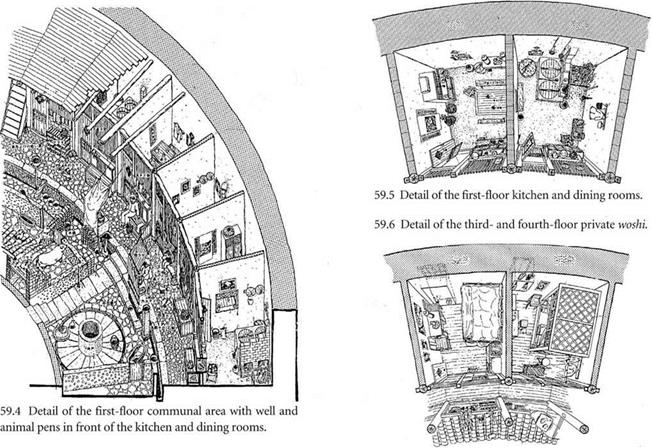

Facing out on the tianjing, woshi form insular private spaces. Woshi floors are wooden, but shoes are not removed before entering.

Whether the overall residential complex is large or small, all woshi are a standard three-by-five to three-by-six meters (9.8-by-16.4 to 9.8-by-19.6 feet) in area, regardless of the resident’s generational standing, wealth, or other individual conditions. The three-meter width is said to have been established to provide passage space of one meter around a bed two meters long.

The fact that standardization was scaled to bedroom furniture implies that the room is used strictly as a private bedroom and is not multifunctional. Expansion of the residence does not involve expanding room size, but simply adding on woshi-tang-tianjing units.

Communal Space: Tang and Tianjing (Huizhou)/ Yuanzi (Beijing)

In contrast to woshi, which are self-contained private spaces, communal tang adjoin the open-air tianjing, which connects to the next tang/ tianjing unit, and so on. Thus the interior of the closed Huizhou residential complex is based on a system which binds “private” to “communal” as one body.

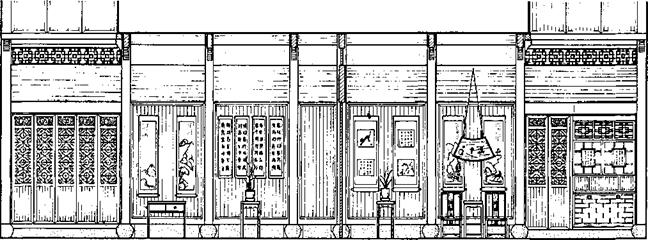

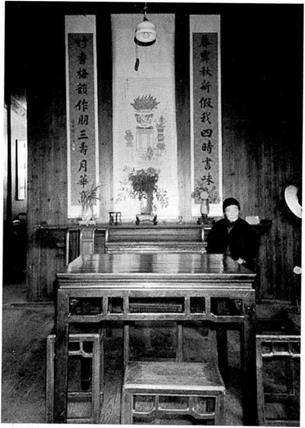

The zutang, or ancestral room, has a solemn atmosphere deriving from its many auspicious decorative elements displayed in hopes of bringing good fortune to the extended family. The center wall of the tang is decorated with a wide hanging scroll which is flanked by a set of calligraphic couplets and in front of which a flower vase, incense burner, bonsai, and table rocks or table landscapes are set. (Here a relationship is evident to Japanese shoin-zukuri, where similar arrangements of imported Chinese scrolls and objects gave rise to construction of the tokonoma alcove.) A square table of rosewood, ebony, or another Chinese fine wood is placed at the center of the wall with a chair to either side—the seats for the eldest couple in the extended family. This arrangement characterizes the highly refined central communal space (Figure 60).

A large table placed at the center of the brick- or stone – floored tang serves as the dining table for one family and is the place where family members enjoy one another’s

|

|

|

![]()

|

![]()

|

|

|

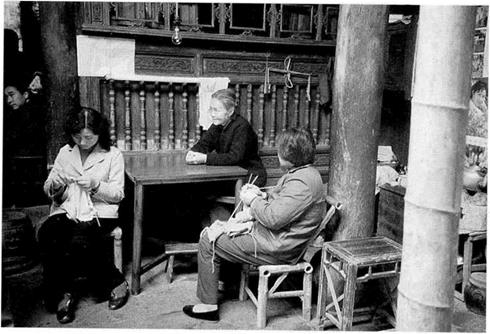

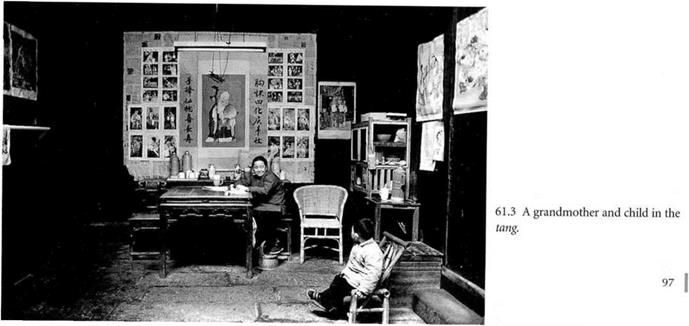

company. It is also where the elderly pass a large portion of the day sipping tea. An array of chairs, including Chinese fine wood stools, bamboo stools, and folding chairs, collect in this room, at times overflowing into the tianjing, at such times the tang and tianjing become one united environment (Figures 61.1-61.3).

The tianjing is not what the Japanese would call a “niwa,” or “garden.” It has the same brick or stone floor surface, and is set at the same floor level, as the tang, forming an open-air extension of the tang. No plants are planted in this courtyard. As communal space, the tang and tianjing

are essentially the equivalent of a living room—with the simple qualification that the tang is closed-roofed and the tianjing is open, functionally they are best interpreted as a single space.

With the entire residential complex surrounded by high retaining walls, the communal tianjing also serves as a link to the outdoors—a means to enjoy natural light, breezes and rain. To the resident looking up from inside the space, the cropped blue sky is dazzling. The space is isolated from the outer world, and so has a certain solemnity. The same objects displayed in the tang—bonsai, and

|

|

|

|

|

|

table rocks or landscapes—are displayed in the tianjing. One specialty of Anhui Province is an almost painfully twisted bonsai; these seem especially well suited to this subdued space.

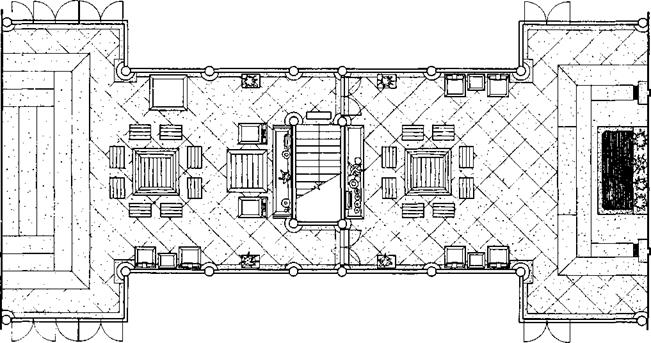

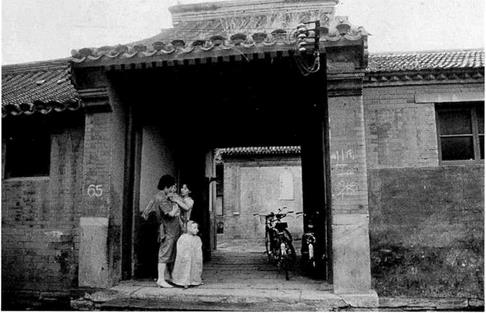

The Huizhou tianjing and Beijing siheyuan yuanzi have similar functions as both are forms of communal space. In Huizhou, the floors of the tang and tianjing are level and have no doors or partitions separating them; there is a greater emphasis on the interconnection between the interior and exterior spaces. In the Beijing siheyuan, the tang is wood-floored and is raised in height and separated from the yuanzi by doors; the sense of integrated space is much weaker than in Huizhou dwellings.

Since the yuanzi is nearly square and its surrounding

halls all just one story high, it lets in far more sunlight and is considerably larger than the tianjing. The tianjing $ functional emphasis gives priority to climate control, which restricts its use; the spacious yuanzi is designed to serve partly as a work area.

The yuanzi is further distinguished from the tianjing in that trees and ground cover are frequently planted in its four corners; the composition, however, is very formal, and there is no intent whatsoever to express natural scenery (Figure 62.1-62.2).