I forewarn all Persons from harbouring him, and Masters of Vessels from carrying him out of the country.30

I forewarn all Persons from harbouring him, and Masters of Vessels from carrying him out of the country.30

Bucktrout, like I lay, expanded his business beyond his craft. After moving from the I lay shop, he operated a retail store where he offered upholstery services and materials, and sold general merchandise. Like Hay’s venture at the Raleigh Tavern, it was apparently cpiite successful, although Bucktrout actively continued cabinetmaking and upholstering. In 1775, having firmly established his second business, he advertised to the public that he “still” carried on the cabinetmaking trade and ended w ith a note that reinforced his intention to continue doing so:

I should be glad to take one or two apprentices of bright Genius, and of good Dispositions, and such whose Friends are willing to find them in Clothes.31

The most informative documents regarding Bucktrout’s furniture are the accounts of Robert Carter, for w hom he made a desk and bookcase in 1769, at a cost of £16.32 In 1772 Carter moved from Williamsburg back to his Westmoreland County plantation, Nomini I (all. Bucktrout not only assisted in packing for the trip but also made new articles for the large country home:

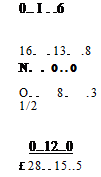

To Benjn Bucktrout

1772

June IS To mending a Music stand

Octobr 26 Mahogy Chares Stufed over the Rails w ith Brass nails (2 £25 per doz I о 4 Flbow Chares (5 55/

Decemr 29 To 65 feet of pine @ 1 1/2 d

To 150 8d nails for a packing Case for Harpsicord 3/ makeing and packing Do 10/

\ ntsburg June 14th 1774 then received of Robert (Carter) the above account in full I say received.

Benjn Bucktrout.33

I he pricing of the chairs per dozen brings up an intriguing question. Did Carter purchase eight chairs out of a set of tw elve that Bucktrout had on hand for direct sale, or does this represent Buck- trout’s usual practice of pricing side chairs? It would seem that if only eight chairs w ere custom ordered, the price would be per chair rather than per dozen.

Consistent with eighteenth-century cabinetmaking in both America and Kngland, Bucktrout also made coffins and directed f unerals. I le served in this latter capacity when V irginia’s Royal Governor, Lord Botetourt, died in 1770. Bucktrout billed the

Botetourt estate “to the I learse and fiting up to carrey his Lordship’s Corps in 6-0-0” and “to four days attendance 2-0-0.” Bucktrout did not make Lord Botetourt’s elaborate triple-case coffin, w hich was constructed by Joshua Kendall, a Williamsburg carpenter-joiner.34 But that same year he did bill Robert Carter for a coffin, and a year later, for a second. These were not simple pine boxes, as often imagined, but w ell constructed, expensive products with great ceremonial significance. One of the Carter coffins, which cost £5, was described as “a neat coffin covered w ith superfine Black Cloth w ith w ite nails lined with flannel”.:!S Lord Botetourt’s coffin was embellished with silver fittings by William Waddill, a Williamsburg silversmith. It is of particular interest here to note that Bucktrout’s employment as an undertaker long outlasted his cabinet trade, surviving to the present day as Bucktrout Funeral Service, one of the oldest such businesses in continuous operation in America.

In addition to his undertaking, retailing, and cabinetmaking businesses, Bucktrout also served as purveyor of public hospitals for the new State of Virginia, lie acted in this capacity from 1777 until the fall of 1779, w hen he offered his house and lots in W illiamsburg for sale. The sale also included a large group of household furniture, “a chest of cabinet makers and house joiners tools,” and “a quantity of very tine broad one, two, and three inch mahogany plank, w hicli has been cut this five years.” I le concluded the notice by stating his plans to leave the colony the follow ing October anil by clarifying his intention to rent his house had it not been sold by that time.3*

Bucktrout’s destination is unknow n; if he left at all, it w as for only a short time. I le w as certainly in Williamsburg by November of 1781, when he w as included in a list of local people alleged to have joined the British army but who had returned after Cornwallis’s defeat at Yorktown.37 Considering Bucktrout’s London background, the accusation is understandable, but the evidence against the charge is very strong. I lis construction of the pow der mill and his public service for the hospitals during the Revolution could hardly be claimed as pro-British. In further support is the announcement of his intention to leave Williamsburg in 1779, when he claimed that his house would be rented if not sold—a highly unlikely proposition for a Tory. Finally, Bucktrout continued to reside in W ilUamsburg until his death in 1813. lie was appointed to public office as tow n surveyor in 1804, and apparently he prospered, for in Williamsburg’s tax list of 1812 he is listed as the ow ner of eight and one half lots.38