A traditional ondol is only effective when used with a flue structure of limited length, and this inevitably limits the size of the rooms in which it can serve as a sufficient heat source.

The basic unit of measure for pang is one k’an (a square

|

|

measure each side of which is equal to the width of the span between columns).8 Occasionally a pang may be one – and-a-half k’an (i. e., having two one-span walls and two one-and-a-half-span walls).

Generally, two of these pang are served by a single ondol furnace/flue system, and the entire length of the heated area is never more than three kan, which is the largest area that an ondol can effectively heat. The pang located closer to the furnace is called an anbang (inner pang), while the other is called an utpang (outer pang).

The floor of the pang is traditionally covered with varnished paper, giving it an amber cast. The walls, the ceil

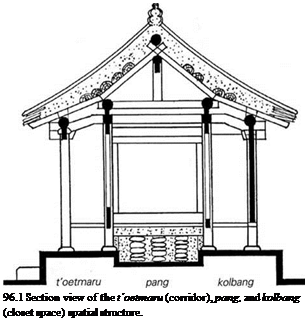

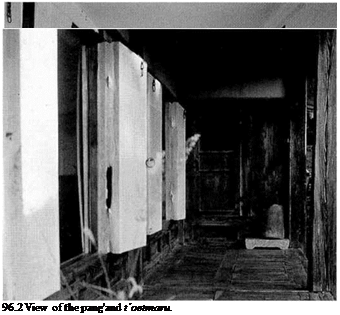

ing, and the inside surface of all the windows and doors are covered in translucent white paper, thus the room is, as a rule, predominantly white (Figure 95). The pang is flanked on either side by a space one-half-/c’cw in width; one, called the kolbang, is used as a walk-in closet, while the other, the t’oetmaru, serves as a corridor (Figures 96.1-96.2).

Anbang

The anbang is the heart of the home, a private space with a wide variety of uses including sleeping, eating, and other daily activities.

The side of the room closest to the ondol furnace—the

|

warmest and hence regarded as the seat of honor—is traditionally reserved for family elders, and the ansok back cushion and other privileged seats are invariably placed along that wall. The adjacent pudk, or kitchen, is entered through a sliding door built into the same wall; the entire wall is normally hidden by a decorative folding screen (see Figure 105.2).

Utpang

The utpang is secondary to the anbang, since its heating is inferior. It is used mainly for storage, as an additional sleeping area, or as a study, but in situations in which a large family must share a limited number of rooms, it often becomes as multipurpose as the anbang.

Anbang and utpang may be completely separate. In other cases, the wall between them may be removed to create a single larger room, or they may be partitioned by removable sliding doors. The latter of these is the most common arrangement. Whatever the preferred arrangement, there are traditionally never more than two pang to a single ondol furnace, and any interior partitioning of the maximum three-A:’an space occurs between the anbang and utpang.

Kolbang

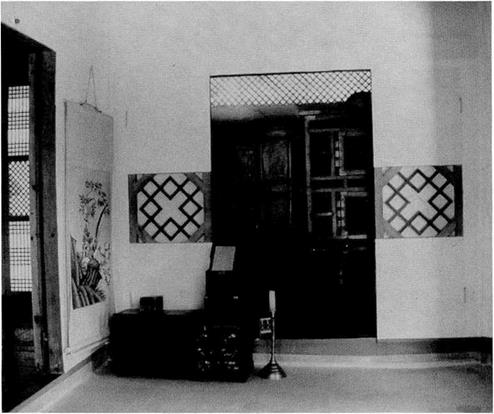

The kolbang is an adjunct to the pang, usually separated

from it by doors that slide into a reveal in the wall. Its main use is as a repository for large pieces of furniture, such as chests of drawers. When not in use, bedding is folded and stored on top of this furniture (Figure 97).

In homes with no kolbang, bedding is stored on top of furniture within the pang, and clothes are hung on special racks.

Kdnndbang

Kdnndbang is the name used for an ondol-heated room located just beyond the taech’dng, on the side furthest from the pudk (kitchen). The kdnndbang has its own furnace and is used as part of the women and children’s quarters, or as a study (Figure 98).

Sarangbang

The sarangbang is an ondoZ-heated room within the sarang – ch’ae. It is traditionally used by the master of the house for receiving visitors, or as a study.

Pudk

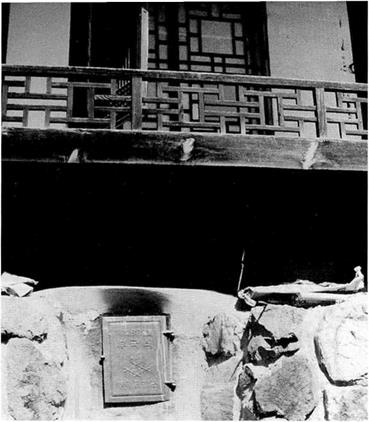

The pudk, or kitchen, is located adjacent to the anbang, and contains a stove built along the wall separating the two spaces. This stove also acts as the furnace for the ondol. Since the furnace needs to be set at a height below the

|

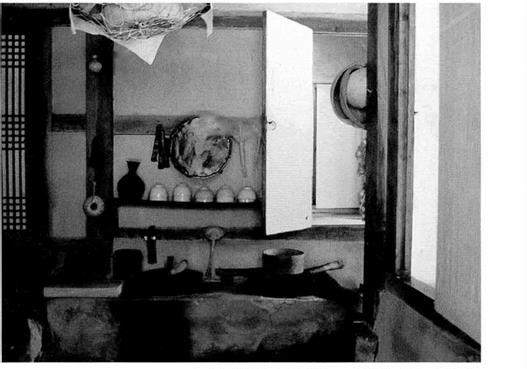

99 A view of a pnok (kitchen) and pang showing a combination stove/ondol furnace.

floor of the rooms which it heats, the pounded earth floor of the puok is generally two steps lower than the floor of the pang (Figure 99).

With the resulting excess ceiling height, a mezzanine is frequently built above the kitchen for use as storage space, called the tarak, which is accessed through sliding doors from the adjacent anbang.

A serving area, or ch’an’ggan, is usually built alongside

the puok. A typical Korean meal consists of rice, soup, and a number of side dishes served in individual portions on papsang (short-legged tables) that are carried to each member of the family or guest seated in the pang or the taech’dng. The ch’an’ggan, like die larger ch’anbbang, or pantry, is used both for serving meals and for storage.

As we can see from the above, the compositional charac-

|

100 Schematic of a rural residence centered on the pudk (kitchen). |

teristics of the traditional Korean residence dictated by existence of the ondol heating system starts with the pudk, or kitchen, almost invariably located alongside the anbang, or the inner of two heated rooms, with the utpang, or outer pang, located next to the anbang. There may also be a third heated room (konnobang) with an independent exterior furnace, located at the far end of the taech’dng. Thus the residence is composed of a series of small ondol – heated rooms one k’an in width flanked by narrow wooden – floored spaces, and open wooden-floored rooms the width of the combined ondol and adjunct spaces. Accordingly, since the ondol is an indispensable part of Korean life, there are traditionally no multiple-story dwellings.

The several factors listed here—the combination of ondol-heated and wooden-floor rooms, the requirements of Confucian morals, the use of divination according to the theories of yin and yang, and the design considerations dictated by p’ungsu geomancy—combined in different situations, in both urban and rural settings, to produce homes that were L-shaped, U-shaped, oblong, or square with an inner garden.