The Chinese yuanlin is composed of some views designed to be appreciated from a seated position at chair height inside the buildings, and others designed to be viewed while walking. In the case of Japanese gardens, there was a gradual development from a static, frontal, unidirectional composition in which the garden was viewed from a seated position inside an adjacent building, then first to viewing from two sides, and finally to sequential and even multifaceted compositions as people penetrated and walked through the garden. By way of contrast, the essence of the yuanlin centers on interdependent mutual and intersecting views between buildings, so that each element of the garden’s composition is multifaceted, multilayered, and kinetic.

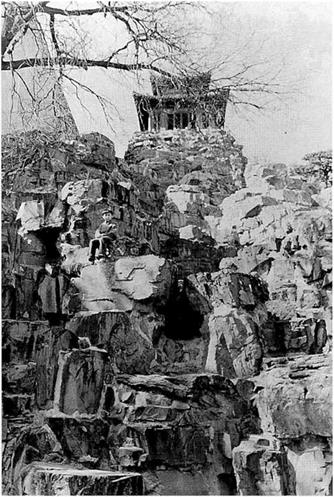

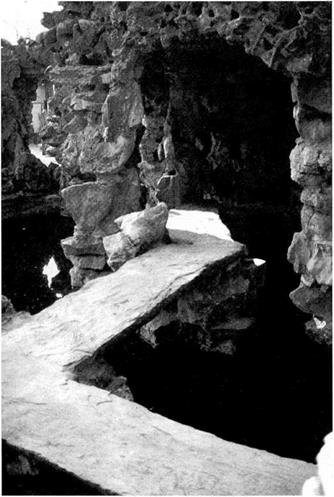

The cities in which the greatest concentration of yuanlin is seen, particularly in the Jiangnan region, are situated on vast plains, which helped to make the themes of “strange and steep peaks” or “waterfalls dropping from steep cliffs” portrayed in Chinese landscape painting popular elements in garden design. Particularly admired were the fantastic rocks evocative of the “oddly-shaped peaks and strange rocks” of mountainous regions. These rocks of different shapes and sizes had to be “fantastic” in appearance and exude “mystical power,” so they were well-suited to the construction of an ideal, otherworldly realm with the huating at its center. Garden makers favored vertical compositional techniques such as “layering” (die) and “piling up” (dui), and pavilions were built on top of piled-up rocks to afford a “high climb, distant view” (denggao yuan wang; Figure 75.1), while caves were cut into layered rocks to provide a space in which to “think meditatively and ponder in silence” (chen si mo kao; Figure 75.2).

In Japanese gardens, artificial hills exist as a compositional element used to create scenery, and are not designed to be climbed. Accordingly, they are constructed not to a human scale, but to complement other compositional elements in the scaled-down landscape. In the yuanlin, however, mountain features are both part of the scenery and also intended to be climbed, and so they are built to a human scale. In this garden then, the same scale governs both the parts of these natural views and the integrated whole. Rocks are categorized as tou (transparent), shou (thin), zhou (wrinkled, or textured) and lou (literally, “leaking”; scattered with small, elongated holes). These criteria for the selection of rocks are a distinctive feature of the materials used in the composition of yuanlin (Figure 76).

Borrowed Scenery (Jiejing)

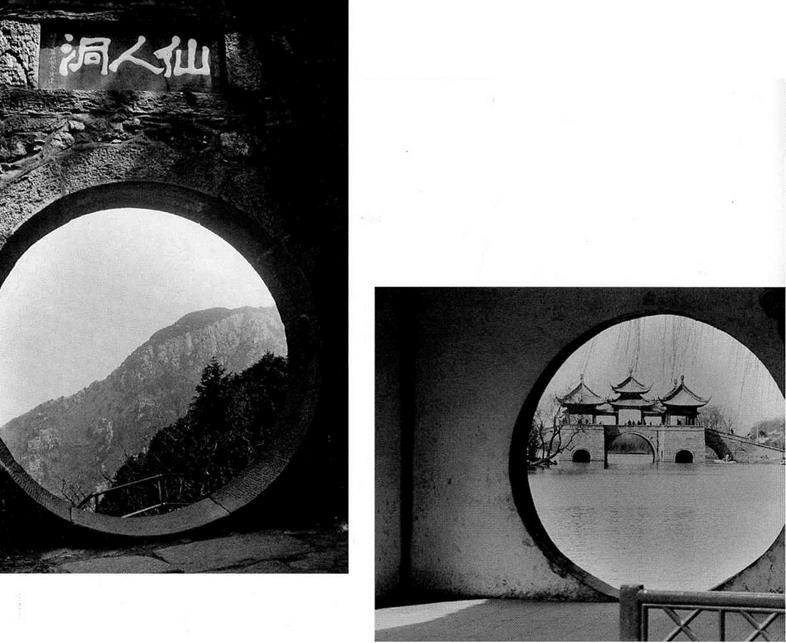

Yuan ye classifies jiejing, or borrowed scenery, into four types.

Yuanjie, or “scenery in the distance,” includes views of mountain ranges, fields, rivers, and lakes seen from a high vantage point (Figure 77.1). Linjie, or “scenery nearby,” refers to views of towers, multi-storied buildings, belvederes, and pavilions of adjoining or nearby gardens. Linjie

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|

|

|

is mainly the borrowing of buildings as scenery, but the term also refers to views of adjoining garden scenes borrowed through latticework windows (Figure 77.2). Yangjie, or “scenery above,” describes scenery such as clouds, light, moon, trees, and towers that is viewed by looking up. Fujie, or “scenery below,” refers to a view of an adjoining garden from above, and is also known as a “stolen view” (duojing).

In the Japanese garden borrowed scenery is distant— for instance, a distant mountain—and is used to impart a sense of the infinite to a comparatively small space, but in the yuanlin, the garden within retaining walls is joined to the outside by means of the borrowed view, with the aim being to fuse the garden with the adjoining scenery. In other words, borrowed scenery in the Japanese garden

liberates the garden from the confines of its site, while borrowed scenery in the yuanlin links one garden scene or “segment” to another.

Private yuanlin landscape park gardens developed from the ting yuan contemplative landscape garden as an area completely distinct from the everyday living hall and courtyard space. The circumstances under which gardens developed in China suggest that the techniques for constructing yuanlin were similar in nature to those used in the garden parks of the nobility. The fundamental purpose of the yuanlin was entertainment, which was provided mainly in the huating. The yuanlin was an expression of the realm of Chinese landscape painting—a real-life version of an ideal world.

|

|

|

|

____________________________________________________