Richmond did not achieve prominence as an urban center until late in the colonial period, and it was not until the capital was moved from Williamsburg in 1780 that it became the focal point for political activity in Virginia. The city blossomed after that date and, like others during the federal period, attracted a community of craftsmen. There is currently no documented furniture from colonial Richmond, and labeled pieces from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries do not retain features from an earlier style. Some unsigned examples have historical circumstances suggesting an origin there and pre-Revolutionary details found on them may provide some clues for the future identification of its early furniture.

Only two advertisements were placed in the Virginia Gazette by Richmond artisans during all of the colonial period—one by the partnership of (dark and 1 lolland in 1774, and another two years later by John Clark. One of the most complete contemporary descriptions of a cabinet shop in colonial Virginia is found in the latter:

Only two advertisements were placed in the Virginia Gazette by Richmond artisans during all of the colonial period—one by the partnership of (dark and 1 lolland in 1774, and another two years later by John Clark. One of the most complete contemporary descriptions of a cabinet shop in colonial Virginia is found in the latter:

RICHMOND TOWN, February 16, 1776

ТІ IK Subscriber intends to leave the colony soon, and will sell (or rent) the LOT No. 28 in the low er F. nd of Richmond, fronting the main and cross Streets, with the following Improvements thereon, viz. a Dwelling-! louse 34 by 24, one Story high, a Brick Cellar of the same size, with a Partition in the Middle, proper for a Cellar and Kitchen, which is floored w ith Brick, a Chimney w ith three Fireplaces, the upper Rooms for a Family to live in, and the lower in Order for a Cabinet-Maker’s Shop, for which it has of late been used; also a Smokehouse, and a Carden in good Order, well paled in. I will likewise dispose of the Benches and Tools, w hich are sufficient to employ six Hands, a Quantity of Walnut Plank, Brass Furniture, Locks, Screws and other suitable articles for the above business.

JOHN CLARK

All Persons who have had Dealings with me, being either Debtor or Creditor, are requested to have a Settlement.’

Clark’s use of his residence as a shop appears to have been a fairly common practice in colonial V irginia, and its size may be typical as well. There were”. . .benches and tools sufficient to employ six Hands. . and its two rooms, measuring a total of 24 feet by 34 feet, gave the workmen an average of 136 square feet of floor space apiece. The Anthony I lay shop measured only slightly smaller in its original form, 24 by 32 feet, and when enlarged had an additional w ing that measured 12 by 32 feet.

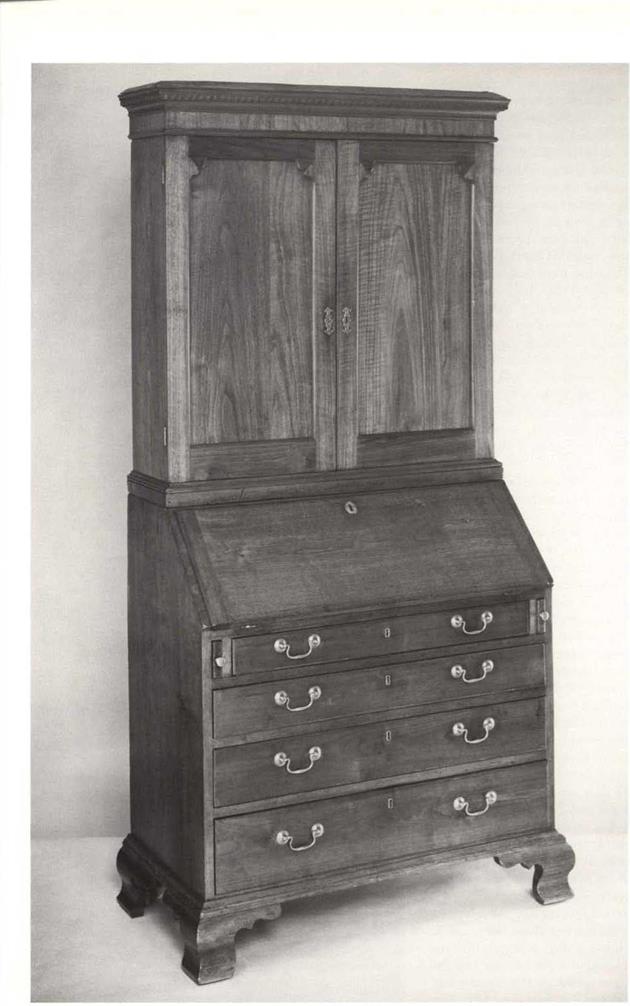

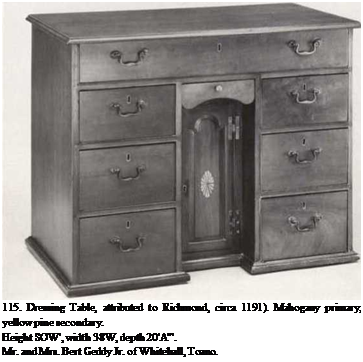

A fall-front desk and a kneehole dressing table that descended in the family of William Geddy, Jr. appear to have been made in Richmond (figs. 114, 115). Geddy’s father was a W illiamsburg blacksmith

|

and gunsmith whose plantation home, “Whitehall,” was twelve miles west of tow n. After the elder Geddy’s death about 1784, his son moved to Richmond, but he returned to Whitehall several decades later.2 These pieces w ere probably acquired in Richmond, for not only do their styles coincide with the date of William Geddy’s stay there but they differ significantly from any known Williamsburg furniture. In fact, they show a close affinity to the products of southeast V irginia, particularly to the dcsk-and-bookcase signed by Mardun F. vcnton of Chesterfield County, near Richmond (fig. 113). Construction details also relate these Geddy pieces w ith others from the general region, although they are much finer and suggest the production of an urban workshop.

The Geddy slant-top desk (fig. 114) is made of mahogany and has yellow pine as the secondary wood in the low er case. The drawers of the w riting interior have Spanish cedar rather than pine as the secondary wood. Found in tropical America, this wood resembles a coarse, open-grained mahogany, and suggests an urban approach to cabinetmaking. It sometimes appears in Boston furniture of the mid eighteenth century, but its principal period of importation was not until the early nineteenth century and later.

The construction of this piece is similar to examples made in southeast Virginia. It lacks dust – boards like many pieces made there, but the deep drawer blades are made of pine and run approximately one quarter of the case depth. They arc faced

with a thin strip of mahogany. The drawer supports are replacements, and it is impossible to know if the originals had V-notches for short rosehead nails, as seen on the Eventon desk-and-bookcase and the accompanying dressing table. The drawer fronts are mahogany veneer on yellow pine, and so is the writing surface on the interior. The runners are replaced, but the drawers retain a series of small support blocks across the front, with approximately one-inch gaps between them. The interior drawer – bottoms fit into a canted rabbet, a feature that is also seen on two desk-and-bookcases (figs. 90, 91).

The construction of the Geddy family dressing table (fig. 115) is related to the preceding piece, but it bears an even stronger relationship to the Eventon desk-and-bookcase and to the southeast Virginia group. Ihc ease has exposed dovetails on the drawer blades and its drawer supports have V-notches to receive short w rought nails. This piece differs from the Eventon desk-and-bookcase in one major construction feature: the dustboards are one-third the depth of the case and are the full thickness of the drawer blades—a type that is found in other southeast Virginia examples and that can be traced to early Norfolk production. Likewise, the base molding on both the dressing table and desk are like those of Norfolk. I hc feet have been lost, but there is ample evidence to suggest that they were straight brackets, reinforced by a single vertical block flanked by two horizontal bracket blocks. These support blocks were made of tulip poplar, and small portions survived when they were split from the base.

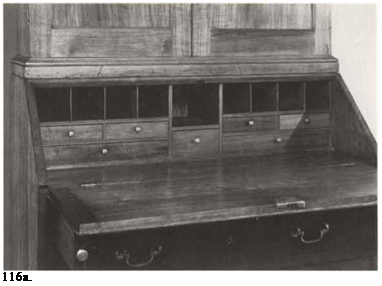

116. Desk-and-Bookcase, Richmond t?), circa 1785. Walnut primary; yellow pine and oak secondary.

Height 83", width 43 W, depth 22".

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (асе. no. 1959-11

|

|

New England influence seen in the Eventon desk-and-bookcasc is also seen on this dressing table. It has cock-beading cut on the drawer blades and on the sides of the case rather than applied to the drawer. The interrelationship of construction and the combination of stylistic features also indicate influences from the North that could have arrived via migrant cabinetmakers or through exposure to imports. These examples are intriguing evidence of the mixing and blending of technology and style from Norfolk, Williamsburg, and New England.

The last example included in this group is a desk-and-bookcase that may have been produced in the Richmond area (fig. 116). It is filled with genealogical inscriptions indicating that the first owner was Edmond Eggleston of Cumberland County, who married Jane Segar Langton from Amelia in March of 1799. It passed to their son Richard, who lived in Nottoway, and descended through his heirs in Culpeper County. The piece then w ent to the Cunningham family of Gloucester County and w as owned by them for several generations until acquired by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1959.3

The last example included in this group is a desk-and-bookcase that may have been produced in the Richmond area (fig. 116). It is filled with genealogical inscriptions indicating that the first owner was Edmond Eggleston of Cumberland County, who married Jane Segar Langton from Amelia in March of 1799. It passed to their son Richard, who lived in Nottoway, and descended through his heirs in Culpeper County. The piece then w ent to the Cunningham family of Gloucester County and w as owned by them for several generations until acquired by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1959.3

Many features on this desk-and-bookcase relate it to cabinetmaking in Williamsburg, but it has several important departures. The coarseness of workmanship and the lack of dustboards point to a source outside the mainstream of that city’s production. One Williamsburg feature is the frame attachment of the bookcase section (see text accompanying figs. 76 -78 and 90-92 for a discussion). This piece provides a stage in the evolution of the frame attachment that is unknown on W illiamsburg examples. The frame is usually joined to the desk section and a separate molding is attached to the bookcase sides to form an interlock joint. Here, both the frame and the molding are joined to the bookcase section, which is secured to the desk by two pegs that project from its base and enter holes in the top of the desk. The Dunmore desk-and-bookcase shows the next stage in this evolution, with the molding attached to the bookcase and w ith four pegs that fit into holes in the top of the desk for stability (fig. 87). There, however, the frame was eliminated entirely. The Eggleston desk-and-bookcase (fig. 116) thereby represents the missing stage in the W illiamsburg evolution from a full interlock joint to a simpler molding attached to the bookcase.

Curiously, the detachable cornice is also held in place by pegs that enter the top of the bookcase. It originally continued into a pediment and could have been either a broken scroll or a pitch form. The flat paneled doors have ogee spandrels of a type seen in Williamsburg (fig. 77) and Norfolk (fig. 105). The

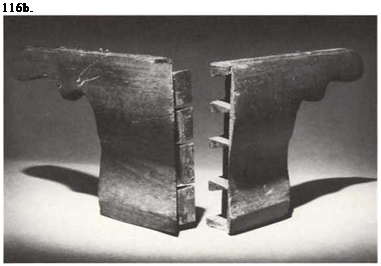

ogee feet have unusual concealed dovetail joints (fig. 116b), a feature seen on at least one Williamsburg example (fig. 88). They are rather stiff in contour, but in this respect resemble those of the John Tyler desk-and-bookcase (fig. 89). Both of these pieces also have straight battens in their fallboard.

This desk-and-bookcase shows an affinity to several eastern Virginia groups, but it is quite different from the Geddy family pieces, which present much stronger evidence for a Richmond attribution (figs. 114, 115). Undoubtedly, further research will eventually isolate the colonial furniture of Richmond, but for now an educated guess will have to suffice.

FOOTNOTES

1. The Virginia Gazette, ed. John Dixon, March 9, 1776, p. 2.

2. I larold B. Gill, Jr., The Gunsmith in Colonial Virginia (Williamsburg, Virginia: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, and Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia, 1974). p. 30.

3. Accession File No. 1959-Ї73, Department of Collections, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia.