On the one hand, children are perceived to be in a state of continuous exposure to unacceptable risk, to themselves and to and from others. On the other hand, we express serious concern that they will become couch potatoes, overweight, underexercised and solitary. Children now consume passively through TV, video and computer games, the thrills, dangers and subversion that John Muir created for himself first hand.

(Children’s cartoons and commercials) portray an abundance of the things most prized by children – food and toys; their musical themes and fast action are breathtakingly energetic, they enact a rebellion against adult restriction; they present a version of the world in which good and evil, male and female, are unmistakably coded in ways easily comprehended by a young child; they celebrate a community of peers.15

Adults’ expectations of children and children’s expectations of themselves are necessarily related. It is possible for adults to confine and regulate children partly because of the escape hatch offered to children by the products of consumer culture. In turn, consumer culture creates for children a hyper-reality, with which they willingly engage. A recent Australian study suggested that although children, even as young as three, were knowledgeable and capable of exercising some scepticism about the claims to reality of what they saw on TV, videos, and computer games, they did not question at all the market culture that gives rise to such advertising and promotion. They took it as normal that such goods would be provided for them, and that they would have endless opportunity to choose amongst them.16

Children’s consumer culture, and the ways in which it is promulgated, are now well-researched areas.17 It is the flip-side of children’s disappearance from public spaces. Children are not merely being protected, confined and contained; they are also offered alternatives and distractions.

Parents are very uneasy about consumer culture, and the breakdown of values it seems to imply.

Parents express a range of concerns to do with the welfare, whereabouts and well-being of their children. Because they are time-poor, they worry that their children receive too little of their

Figure 9.4

Figure 9.4

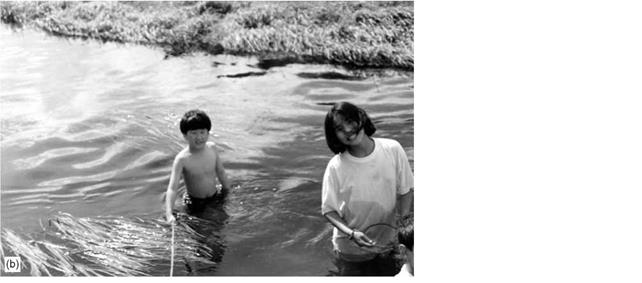

(a) Advertising is almost everywhere within the modern urban environment encouraging children to demand and challenge in order to get what they want. (b) By comparison children in more traditional rural communities, such as these Thai children on a school field trip, are more physically active and connected to the sensory pleasures of the natural environment. Their public spaces are far less commercially orientated. (Photos: Michele Oberdieck.)

Availat

|

time and energy. They thus involve them in more and more supervised activities. They also worry that their children need more protection from a world that is losing a sense of belonging and increasingly seen as hostile as a result of drugs, heightened violence and abuse… Because they have raised their children on the principles of child-centredness, they worry that they have been perhaps too open, too permissive, and somehow

contributed to difficult-to-deal-with behaviour… They fear that they have over-indulged their children, over-compensated for their own parental deficiencies through consumer goods, overexposed them to the more adult themes of life1

Some researchers consider that the media exploit and exacerbate these fears. Certainly there is good

|

Figure 9.5 The Kindertagesstatte, Neukolln, Berlin. One of the new generation of daycare facilities for children which are high cost, dawn till dusk, highly institutionalized ‘child parks’, which reassure parents that their young children are well looked after. Parents can work or play for the whole day whilst their children are educated. (Photo: Ulrich Schwarz.) |

evidence to illustrate the enormous sophistication, complexity and reach of market campaigns aimed at children and their parents. Advertisers of commercial products encourage children to demand and challenge in order to obtain what they want (or what is being promoted) and at the same time play on the guilt feelings of their parents. Cartoons, commercial TV, film and advertising simultaneously promote, and offer opportunities to resolve, inter-generational conflict.19

Young children have proved a lucrative market for the exploitation of parental inadequacy. All

manner of toys are marketed as ‘educational’. Our mission is to provide families with a HUGE selection of creative and stimulating products in a customer-friendly entertaining and interactive shopping environment because we believe kids learn best when they’re having fun.’20

Parents and childcare workers alike have come to believe that nurseries should resemble shopping malls, in their reproduction of continuous multiple choice. Writing about American preschools, Tobin comments that:

Customer desire is reproduced by the material reality of our preschools. The variety of things and choices offered by middle-class preschools is overwhelming to many children. We create overstimulating environments modelled on the excess of the shopping mall and amusement park… We have become so used to the hyper-materiality of our early childhood care settings that we are oblivious to the clutter; settings that provide more structure and are less distracting seem stark or

bleak.21

Harry McKendrik carried out an analysis of privately provided play settings; private out-ofschool clubs but also at leisure centres, shopping malls, pubs, and other entertainment centres. He concluded that children had relatively no say or control in determining their access and use of such places; they were ‘parked’ there by adults who had other agendas – to shop or to socialize or to exercise. These playspaces were marketed as an opportunity to provide parents with free time, whilst their children were ‘educatively’ and safely cared for.22