In his book, The School and Society, John Dewey, one of the key educational pioneers of education during the twentieth century, states:

What the best and wisest parent wants for his own child, that must the community want for all its children. Any other ideal for our schools is narrow and unlovely; acted upon, it destroys our democracy.5

What values from our homes, our communities, and our democracy do we wish to communicate to children through architecture, both overtly and symbolically? What is the reality of the child’s experience?

We are all familiar with the traditional public school where, in the words of Robert Sommer:

‘Movement in and out of the classrooms and the school building is rigidly controlled. Everywhere one looks there are “lines" – generally straight lines that bend around corners before entering the auditorium, the cafeteria, or the workshop (or,

I might add, the bathroom). The straight rows (of the classroom) tell the student to look ahead and ignore everything except the teacher; the students are so tightly jammed together that psychological escape, much less physical separation, is impossible. The teacher has 50 times more free

space than do the students with the mobility to move around… teacher and children may share the same classroom but they see it differently.

From a student’s eye level, the world is cluttered, disorganized, full of people’s shoulders, heads and body movements. His world at ground level is colder than the teacher’s world.6

This cannot be what the wisest and best parents want for their children or what the democratic society wants for its children. By comparison the model home is warm, loving, and beautiful; the complete community is fair, cooperative, collaborative, and respectful; democracy requires inclusion, commitment, and justice.

|

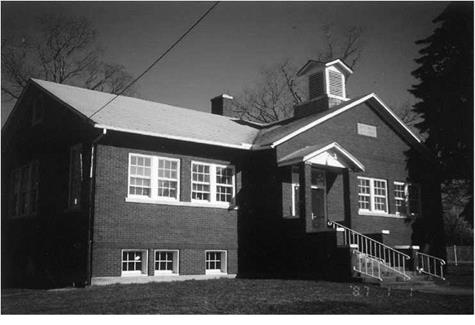

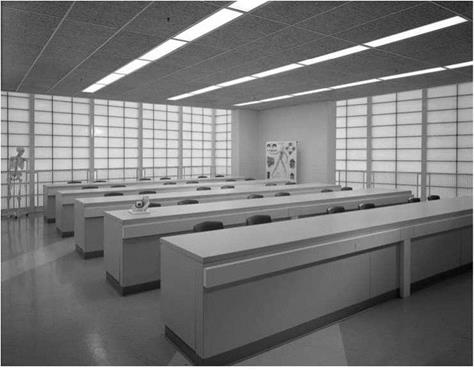

Figure 4.2

Figure 4.2

Racht School, Harbert, Michigan, 1928. The two images on this page illustrate the intermediate development of the American school from the earliest nineteenth century school houses (see Plate 4) to the large – scale developments from the 1940s onwards. Note the iconographic architectural references to the home and the church seen here in these two examples (Photo: Eleanor Nicholson.)

|

There have always been schools that abide by these values. Even in fifteenth-century Mantua, Vittorino da Feltre, at the behest of the Gonzaga family, created a school that represented the best in humanist thinking and could take its place today as a humane yet challenging school environment for children. When the Gonzagas asked Vittorino, one of the foremost scholars in Italy, to establish a school for their children and the children of other prestigious Mantua families, it was a little like asking one of the Nobel laureates from the University of Chicago to go over and teach in a Laboratory School. The Gonzagas offered Vittorino a beautiful palazzo for his school, La Joiosa, or what might be translated as ‘the Pleasure House’. Vittorino changed the name to La Giocosa, stripped the place of its opulent furnishings, decorated the walls with frescoes of children at play, and let the light and air in through the tall windows and spacious halls. It was open to all children, not just the aristocratic friends of the Gonzagas, but children of scholars and of the poor, whose tuition was paid for by Vittorino. They all wore the same simple clothing, regardless of rank. The children played in the meadows in front of the palazzo. Vittorino took them on field trips, tutored them individually as well as

collectively, and watched over their health like a protective parent.

Vittorino’s model, alas, saw little replication in the centuries that followed. To pick up the threads of this humanistic approach we can turn to some exemplary early nineteenth-century thinking. Horace Mann, father of the Common School in the United States, was outspoken in his feelings about the school architecture of the time. In 1840 he wrote the following:

The voice of Nature, therefore, forbids the infliction of annoyance, discomfort, pain, upon a child, while engaged in study. If he actually suffers from position, or heat, or cold, or fear, not only is a portion of the energy of his mind withdrawn from his lesson, – all of which should be concentrated upon it; – but, at that indiscriminating age, the pain blends itself with the study, makes part of the remembrance of it; and thus curiosity and the love of learning are deadened, or turned away towards vicious objects.7

The essay continued:

The first practical application of these truths, in relation to our Common Schools, is to

schoolhouse architecture, – a subject so little regarded, yet so vitally important. The construction of schoolhouses involves, not the love of study and proficiency only, but health and length of life…It is an indisputable fact that, for years past, far more attention has been paid, in this respect, to the construction of jails and prisons, than to that of schoolhouses. Yet, why should we treat our felons better than our children?7

Deeply concerned about poor ventilation in the schools of the day and dripping with irony, Mann continued his essay:

I have observed in all our cities and populous towns, that, wherever stables have been recently built, provision has been made for their ventilation. This is encouraging, for I hope the children’s turn will come, when gentlemen shall have taken care of their horses.7

And finally,

I cannot here stop to give even an index of the advantages of an agreeable site for a schoolhouse: of attractive, external appearance; of internal finish, neatness, and adaptation.7

This particular lecture by Horace Mann covers a great many other topics in addition to school architecture, among them the multiplicity of school books, which he ascribes in part to the profits book companies wished to make out of the constant replacement of old, nevertheless usable books with new ones. He called for ‘apparatus’ which would ‘employ the eye, more than the ear, in the acquisition of knowledge’. Such manipulatives, as he would call them, would include a globe, a planetarium, microscopes, telescopes, and prisms. Clearly he wished children to experience much more practical instruction over and above the purely academic lessons with children sitting passively, hearing and listening.

He discussed libraries, curriculum reform, corporal punishment, and teacher training. Throughout the lecture there emerges a passionate interest in the needs of children, how they should learn, and how they should be taught. Unlike the stern Puritans who came before him and like the child-centred educators who came after him, Mann believed that the child was innately curious, eager to learn and capable of assuming responsibility for things of beauty and value. ‘Nature has implanted a feeling of curiosity in the breast of every child, as if to make herself certain of his activity and progress’. He believed that children enjoyed finding things out in their own way and in their own time. Before the argument is raised, ‘that mischievous children will destroy or mutilate whatever is obtained for this purpose [apparatus]’, he countered,

But children will not destroy or injure what gives them pleasure. Indeed, the love of malicious mischief, the proneness to deface whatever is beautiful, – this vile ingredient in the old Saxon blood, wherever it flows, originated and it is aggravated, by the almost total want, amongst us, of objects of beauty, taste, and elegance, for our children to grow up with, to admire, and to protect.8

Mann would surely have hoped that the messages of the school building itself, as well as what is inside it, would proclaim to children the importance of beauty, taste and elegance.

With the diffusion of the various forms of childcentred active education into the mix, new ideas of beauty, respect for the child and attention to his or her developmental needs – emotional, physical as well as intellectual – entered the architectural consciousness during the second half of the twentieth century. Building on Froebel’s Kindergarten ideals, succeeding waves of schools – progressive schools, Montessori and Waldorf schools – have all reflected and shaped new ideas about education. Almost unique in the present educational climate are the pre-schools in Emilia Romagna, Italy. There, an early years system has evolved which illustrates a clear philosophical commitment to architecture and its role in learning – the so called ‘third teacher’. The words of Lella Gandini demonstrate explicitly that schools have messages:

The visitor to any institution for young children tends to size up the messages that the space

gives about the quality and care and about educational choices that form the basis of the program. We all tend to notice the environment and ‘read’ its messages or meanings on the basis of our own ideas. We can, though, improve our ability to analyze deeper layers of meaning if we observe the extent to which everyone involved is at ease and how everyone uses the space itself. We then can learn more about the relationships among children and adults who spend time there.9

The underlying assumption of the Reggio approach is that space matters enormously. It reflects the vision of those who inhabit it and it shapes those visions. The system recognizes that children are born with a natural sense of exploration and that they interpret the realities of the world through their senses of touch, sight, smell and hearing. Neurobiological research has demonstrated how important this dimension is to children in their development of knowledge and the important social concept of a group memory. It follows that unstimulating environments tend to dull or deafen the child’s perceptions. Schools must be capable of supporting and stimulating sensory perceptions in order to develop and refine them. This is an essential aspect of education, part of the hidden curriculum if you like.

|

|

The messages of the Reggio approach are transparent and powerful, both spatially and philosophically. Communication is the core of their research-orientated approach to pedagogy. Encouraging communication between three subjects – children, teachers and parents, makes these ‘community-orientated’ projects in a real sense. Whereas many childcare centres and most schools exclude parents ‘at the front door’, at Reggio childcare centres, there is always a large community space at or around the entrance where parents can linger and even participate in some of their child’s activities. However, the listening or so-called ‘pedagogy of relations’ does not stop at the doors of the childcare building. Rather, the listening and collaboration take place on a city-wide basis and even spread to other cities and cultures. Given that fundamental premise of communication by the building, it might be explained as a second skin that covers the school, a sort of child-orientated architecture overlying the basic architecture. Therefore, a number of spatial characteristics follow, such as walls where displays of all kinds are presented in a coherent and aesthetically pleasing way, and different and varying levels of transparency between spaces inside (windows between different functional spaces which permit views which may be altered

with curtains or blinds, for example). This ensures that the environment reflects and communicates the life of the school and the activities carried out with and by the children. What Reggio describe as filter zones are also needed, situated outside but close to the classrooms. This enables an easy and unhurried exchange of information in the daily communication with the families and the children. It is also important that each space within the childcare centre is organized efficiently so that the work and projects carried out with the children can be documented. Each child (with its parents) develops a scrapbook to maintain a ready record of his or her progress. This then forms part of a growing archive to aid knowledge and understanding for future generations.

Philosophy, programme and architecture go hand in hand in the Reggio approach, thanks to a combination of superb care and education which is matched by excellent local state funding. At Reggio, you cannot talk about the architecture without understanding the education or pedagogy. They are mutually dependent.

In spite of the possibilities that exist for the development of schools that respect and facilitate the holistic development of the child, generally we are stuck with the facilities of yesteryear. Many of

the public schools in the great urban centres of the United States were built in the very latter years of the nineteenth century and the first two or three decades of the twentieth century. At that time, immigrants from central Europe and from the American South were coming to the USA on a daily basis and in their thousands. The Northern cities required new schools and they were needed in a hurry. Furthermore, the kind of research that has been done in recent decades into issues of child development, meaningful curriculum, and optimum teacher education was not available at that time.

|

|

Then, children were expected to be docile, obedient, and industrious; they were likely to be punished physically if they were not. The thought that children might enjoy school and actually might want to learn seemed to be an alien concept. For teachers, often young and with little training themselves, control was the overriding issue. The curriculum focused on the three ‘Rs’. That was believed to be all that was required in a society in which most students could anticipate a life spent in low skilled factory work. It is easy to see why, given these considerations, the urban public schools built during this period are large, cold, even in some cases, forbidding. Classrooms are planned to cater for as many as forty or forty-five children. The

|

|

teacher is in a central position of surveillance. This is the overriding design principle; it is a message which is not lost on the children.

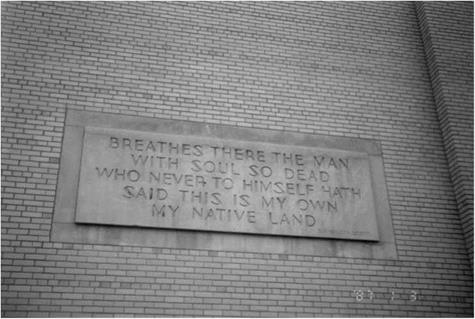

These massive structures are forbidding yet some of them were softened and humanized by the inclusion of important details. For example the plaques on the exterior walls of William B Ogden Public School in Chicago explain to children the

value of academic excellence, and the life of the mind. In their pure simplicity they communicate the importance of the American dream as propounded by Horace Mann. The message of a love of country was considered to be important for a relatively young nation, its cities filling up with immigrants. The individual ethnic identity of the immigrant families was not questioned, rather it

|

|

was complemented by the celebration of the new place in which they found themselves and all that had to offer. Ogden School, even in a busy urban area, strives to create a beautiful surrounding for its huge institutional form. As part of an urban community, Ogden welcomes neighbours to its asphalt-covered playgrounds by inviting them through an ornately inscribed iron gate which literally asks them to respect their environment, and trusts that they will do so. Ogden’s gracious invitation for all comers to use the grounds is a contrast to the more typical dictate of the average Chicago public school. These are clear iconographic messages, legible, and articulate, if a little doctrinaire. The building speaks.

Another and older example of architecture that communicates consistent humanistic messages to American children is Crow Island School in Winnetka, Illinois. Now over sixty years old, Crow Island is a designated national historic landmark. The school is what it sets out to be; in the words of Francis Presler, Director of Activities at Crow Island (whilst briefing the architects Eero Saarinen and Dwight Perkins in 1938) the school was to be ‘a place that permits the joy in small things of life and in democratic living’, ‘a place for use, good hard use, for it is to be successively the home, the abiding place for

the procession of thousands of children through the years’.10 He continued,

‘The school must be honest and obvious to childish eyes as to its structure, its purpose, its use, its possibilities. Strength shall be evident. Genuineness shall be visible. Materials shall say “things are as they seem.”…It must be inspiring, with a beauty that suggests action, not

passiveness on children’s part____ It must be

democratic. That above all is necessary. School must not create an illusion, otherwise children will fail in more mature life. The classrooms shall express inner tranquility that can be sustained. The atmosphere of these rooms, which particularly are the school homes, should give feeling of security. These are especially the places of living together and should give feeling of inviting home-likeness.’

Note the emphasis on home spun values: home, democracy, security, beauty, action, tranquillity and continuity. Crow Island consciously, and to a unique degree, offered an education tailor-made to the emotional and cognitive needs of the younger child, and the building itself played a fundamental role in their education. The task of this age is to achieve

competence at useful skills and tasks, and develop a positive self-concept, pride in accomplishment, and the ability to participate cooperatively with age mates. The honest forthright way in which Presler speaks mirrors the dawning sense of moral responsibility inherent in Erikson’s tasks, while the tactility of the building’s materials reflect the concrete nature of the thinking of this stage of child development, as outlined by Piaget, that children learn through all the senses. Crow Island classrooms fully meet standards for the physical setting as outlined by Sue Bredekamp and Charles Copple in Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs:

Space is divided into richly equipped activity centers – for reading, writing, playing math and language games, exploring science, working on construction projects, using computers and engaging in other academic pursuits. Spaces are used flexibly for individual and small-group activities and whole-class gatherings.11

For the fiftieth anniversary of the school in 1990, 400 Crow Island alumni completed a questionnaire that probed specifically the effect of building design

on their early learning. Here are some of the statements from the alumni:

‘At Crow Island I felt at home.’; ‘Crow Island just always felt cozy’; ‘The building was very friendly and comfortable for us little ones, even then we knew it.’

Children’s physical needs were considered and respected. Every classroom has its own bathroom accessible directly. A general comment made time and time again was the fact that as children they did not have to ask to go to the bathroom or to go down the hall to get to it as is generally the case. Perhaps you have seen children in public schools lined up at an appointed time so all can go to the bathroom one by one while the others remain in straight lines waiting. What adult would suffer the humiliation of being told that she or he may go to the toilet only at a given time?

|

|

Seats in the assembly are graduated in size, with those for the youngest in the front of the room. Light switches and door handles are at child level. Window openings are safe, yet accessible to children’s hands so they can provide ventilation under adult supervision. Children felt safe there. Different ages played in different age-related playgrounds. Doors were colour-coded so a child could always find his or her own room.

Children’s work was respected. ‘We could build things in the workroom and leave them up ’til we finished them.’ Children’s work was displayed elegantly in the classrooms and in the halls.

Children were affirmed in their growing stature, skills and power. It was ‘a wonderful moment when I moved to a new wing of the school (and) became a BIG kid’. Classrooms were orientated in different directions so that ‘In each grade you looked out onto a whole new world as you changed wings’. Thus, the change from one grade to the next gave the child new perspectives on the environment around them.

The outside play areas were accessible directly from the classrooms. Large full height windows give views into the woods surrounding the site to provide a stimulating alternative to class lessons. The close proximity of each classroom to the outside areas extends a sense of space and light. As one former pupil remarked… ‘the windows to the courtyards and the wings gave the feeling of endless space’.12

Attention to natural as well as man-made beauty is manifest everywhere. Natural materials – wood and brick – are used inside and out. Sculptures enhance the environment, acting as fixed features, complementing the evolving displays of children’s art. In my view, all spaces in the school have distinct

messages for the children. There is an assembly hall rather than an auditorium, because auditoriums are only for listening. Presler’s stated goals for the assembly were clear.

The assembly has a unique place in the school. It is the one part of the building in which all come together simultaneously, obviously, and consciously

to form the school body as a whole__ The room

must have dignity for large group consciousness’ sake. It must be buoyant for emotion’s sake. But it must not be adult, sophisticated or overstimulating. It may awe slightly – for children must be lifted to levels they did not know were inside.13

There was to be an art room where, according to Presler, ‘.beauty should be a background setting kind, and one not too finished, lest children feel it beyond them to make contribution’. The library was a place for ‘lingering with energy’ while the shop and science room should say to children, ‘This is your place of finding out, of trying out, of doing and making’. This charge to the architects is consonant with the standards of developmentally appropriate practice:

|

|

The curriculum is implemented through activities responsive to children’s interests, ideas, and

everyday lives, including their cultural backgrounds’".

It is interesting to reflect upon what alumni remember from their childhood at Crow Island. Were they aware of the kind of messages being communicated to them when they were children? Harlan Stanley, who attended Crow Island in the 1950s, recently shared some of his memories with me. He recalled the auditorium with its seats in graduated sizes to fit differently aged children, the sense of privacy in the classroom courtyards, the fact that the door handles were at child level, and the ease of movement around a single storey building with broad well-lit circulation areas. ‘We took these things for granted at the time. Only in going back later did we understand what it was all about’.14

What is surprising about the alumini survey is that the memories are mostly positive and remain vivid to this day; particularly in relation to the architecture itself. Children felt special attending the building, particularly in its early years; there was something communicated through the building fabric that could be later understood. Interestingly, Harlan’s memories were more affecting than most of his more recent adult experiences. This, he assumes, is because children are so open to their experiences during these formative years. They have not yet learned the adult ways of sifting out unwanted sensory information which they do not perceive to have instant value. This view is supported by the words of John Holt:

We all respond to space, but most adults so seldom see a space that they want to and can respond to that we lose much of this sense. Our surroundings are often so ugly that to protect ourselves we shut them out. Children, on the whole, have not learned to do this.15

Does the building enhance learning? There is no hard evidence to support a connection between the built environment and academic attainment. But the kind of learning supported at Crow Island is appropriate, non-verbal, intangible, symbolic and long lasting. Children must be challenged educationally, however the wisdom emanating from the building itself is explicit: children deserve and flourish in an atmosphere of love, community, mutual respect, beauty and a connectivity to nature. These are truths that we probably knew all along, however it is important to hear the comments of some of its alumni affirming these views.

The Reggio schools are for very young children, infants, toddlers, and preschoolers; Crow Island is an elementary school. They are separated in time by World War II and in distance by thousands of miles. But both systems communicate through their very buildings, important messages about the developmental needs of the children who attend them and they succeed uniquely in the positive support of young developing minds. What kinds of school buildings come to mind when we turn to members of that prickly, volatile group – the adolescent middle schooler? What is, in fact, a middle school?

In School and Society, John Dewey outlined his historical analysis of the development of the American school system. Decrying waste in education, Dewey said, ‘I desire to call your attention to the isolation of the various parts of the school system, to the lack of unity in the aims of education, to the lack of coherence in its studies and methods.16

Dewey outlined the differing origins of the eight key blocks of the educational system. According to him, the aim of the kindergarten should be to support the moral development of children rather than to instruct them in a disciplinary way. The primary school developed during the sixteenth century when, along with the invention of printing and the growth of commerce, it became a business necessity to know how to read, write, and count. The aim was a practical one; getting command of that knowledge was not for the sake of learning, but because it gave access to careers in life otherwise closed. This is a principle adhered to by most contemporary elementary school systems.

Dewey’s historical analysis proceeded to the grammar school or intermediate school and the high school or academy. Originally their aim had been to counter the elitist character of the university by enabling ordinary people to access learning so that men could broaden their horizons. That larger horizon originated in the Renaissance when Latin and Greek connected people with the cultures of antiquity. The aim of the grammar school and secondary school education was therefore to promote culture, not discipline. Dewey continued:

It is interesting to follow out the interrelation between primary, grammar, and high schools. The elementary school has crowded up and taken many subjects previously studied in the old New England grammar school. The high school has pushed its subjects down. Latin and algebra have been put in the upper grades, so that the seventh and eighth grades are, after all, about all that is left of the old grammar school. They are a sort of amorphous composite, being partly a place where children go on learning what they already have learned (to read, write, and figure), and partly a place of preparation for the high school. The name in some parts of New England for these upper grades was ‘Intermediate School’. The term was a happy one; the work was simply intermediate between something that had been and something that was going to be, having no special meaning on its own account17

Believing that the different parts of the system were separated historically and had differing ideals ranging from moral development and general cultural awareness to self-discipline and professional training, Dewey concluded that the challenge in education is to establish the unity of the whole system, in place of a sequence of more or less unrelated and overlapping parts. Dewey recognized the need to reduce conflict and repetition within the disparate systems.

The need for a proper bridge between lower and upper schools became more and more evident as the decades passed. The methods used in the middle school made it a high school in all but name. In the traditional junior high, students changed classes at the end of each subject period, classes were of a given length and were taught at a given time. Teachers taught one subject four or five times a day to different groups in succession.

In 1968, British educator Charity James laid out a series of desiderata for the improved intermediate school. She agreed with Dewey’s view that there is no justification in the profound social differences between the elementary and the junior high school. This is a time during young people’s lives when they are embracing puberty and the profound personal transformation that entails:

… can we really be content with the way our young people’s days are spent? Would we allow them, if we had a choice, to spend this time in squads (groups is too rich a word) being addressed or grilled by adults, one adult after another, in totally incoherent order? . Would we not like them to work cooperatively rather than in a moral climate so competitive that sharing is denigrated as ‘cheating’ and actually punished?18

James is concerned with the arbitrary structure of the school day, divided as it was into 45-minute lesson periods, punctuated by the violent clanging of bells. And between each lesson, class groups moved around the building, creating log-jams in corridors and at classroom entrance areas. This planned incoherence does not treat people as individuals and thus negates the rhythms of learning that different individuals have at this time. She emphasizes the critical nature of these adolescent years and asks for new possibilities for individual learning to replace the group mentality. She questions the necessity for middle (high) school children to move around their school buildings all day, whereas elementary school children, by and large, stay put. For James, these are not merely organizational issues. The continuation of these practices is inimical to adolescent growth, if not even dangerous.

This urgency is echoed by Erik Erikson, for whom adolescence was a life stage of particular characteristics, tasks, and challenges. In his essay Youth: Fidelity and Diversity, Erikson states, ‘In no other stage of the life cycle, then, are the promise of finding oneself and the threat of losing oneself so closely allied’. The fact that the emergent adolescent can, as Erikson interprets Piaget, ‘now operate on hypothetical proposition, can think of possible variables and potential relations, and think of them in thought alone, independent of certain concrete checks previously necessary’, can mean an investigation of happenings in reality and a consideration of other possibilities, often with an idealistic or ideological thrust. Adolescents are deeply concerned about issues of fairness and justice, both as applied to themselves personally and to society and societies as a whole.

At the same time, their emotional and physical development has taken an entirely different turn. The individuals in this age group are often characterized by mood swings, uncertainty, selfabsorption, an evolving discovery of the self and its identity, a focus on the peer group, a need for supportive caring adults (while seeming to reject them), and a need for active learning. Their bodies are developing with dazzling and confusing rapidity; their energy levels are high and outlets for that energy are essential. Their ability to think abstractly has soared, while their ability to handle life calmly and acceptingly, as is characteristic of the successful younger child, has been for the most part set aside.

Adolescents are developmentally unique. They are different from the elementary children they so recently were, different from the high school students they will become, different from each other, and different from week to week, day to day, and hour to hour.

Maria Montessori, whose schools for preschool and elementary children are familiar to us, also planned a less well-known programme for adolescents while also rejecting the contemporary secondary school programme. Describing the child from 12 to 18, she wrote:

The secondary school as it is at present is an obstacle to the physical development of adolescents. The period of life during which the body attains maturity is, in fact, a delicate one: the organism is transformed; its development is rapid. It is at that time so delicate that medical doctors compare this period to that of birth

and of the rapid growth of the first years_____

This period is equally critical from the psychological point of view. It is the age of doubts and hesitations, of violent emotions, of discouragements. There occurs at this time a diminution of the intellectual capacity. It is not due to a lack of will that there is difficulty in concentration; it is due to the psychological characteristics of this age. The power of assimilation and memory, which endowed the younger ones with such an interest for details and for material things, seems to change1

Montessori compares the relative stability of the elementary school to that of the secondary school. There, the student changes teacher almost every hour. Montessori believes that it is impossible for the adolescent to adapt to a new teacher and a new subject every hour. Change brings mental agitation. A large number of subjects are touched upon, but all in the same superficial way.

Charity James called for middle schools that were to be totally different from the ‘bossocracies’ of the day where ‘the value they represent is power, not growth. They mirror a social condition outside the school which is destructive to human dignity and ultimately endangers the species’. What she calls for are schools for adolescents that are non-bureaucratic, characterized by small groups, community involvement, an open evolving interdisciplinary curriculum, and teacher collaboration, all aimed at establishing loving, truthful, and hopeful human relationships. Human diversity should be respected and celebrated.20

Montessori recognized similar educational problems and envisioned the same kind of problematic atmosphere for the adolescent as a consequence. Reflecting on her background developing schools in the urban slums of Rome during the 1930s, her model school was to be in the country. There, the child would be outside his or her habitual surroundings in what she viewed as a peaceful place, in the bosom of nature. Perhaps most contentious was her view that the adolescent child should develop better outside the family, a painful by-product of her model school.

Her programme, called ‘Erdkinder’, or ‘Children of the Soil’, would provide experience in agricultural work, running a shop and maintaining a hotel annex for parents or guests who might visit. The work with the soil would offer an educational curriculum with a limitless study of scientific and historical subjects. Living outdoors in the open air, with a diet rich in vitamins and wholesome food furnished by the nearby fields would improve health. The harvest that followed the agricultural labour provided by the children would be sold and the funds from the sales would constitute an initiation to the fundamental social mechanism of production and exchange, the economic base on which society rests.

Thus, her visionary programme was to be self- contained, self-governing, and self-supporting. The environment was to be respectful of children and adults, and essentially collaborative rather than dictatorial. However there would need to be strict rules to maintain order and assure progress.

Montessori first published her insights into the nature of the adolescent in 1939. She herself summarized her vision as one where children would no longer take examinations in order to move into higher education. Rather, the secondary school would be a place where individuals passed from a state of dependence to a condition of independence through their own efforts, working within a living community. Although she never realized her agricultural society school, the message was a good one in its proposition that a school based on a collaborative social model connected to practical rather than theoretical activities would be more effective for the majority of adolescent children.

In 1973, the National Middle School Association was founded in the United States to improve the education of young adolescents. In 1985, the National Association of Secondary School Principals was responsible for the publication of An Agenda for Excellence at the Middle Leve/;this was followed in 1989 by the landmark report of the Carnegie Council for Adolescent Development, Turning Points: Preparing American Youth for the 21st Century. Echoing both Maria Montessori and Charity James, the task force found ‘a volatile mismatch… between the organization and curriculum of middle grade schools, and the intellectual, emotional, and interpersonal needs of young adolescents’. The report set forth recommendations for transforming the education of young adolescents. These have been examined, modified, expanded, and made more meaningful both by a revision of the 1989 report entitled Turning Points 2000: Educating Adolescents in the 21st Century and various reports of the National Middle School Association, culminating in their publication, This We Believe. and Now We Must Act.

In its work on best middle school practices, the National Middle School Association promotes a view of the middle school student characterized as one who wants to be seen as competent, accountable and responsible, as individuals who wish to be respected by peers and adults, as good people of high moral standing, concerned about justice and fairness.21

Such qualities will emerge and be supported in an environment that offers an integrated interdisciplinary curriculum, experiential learning, ample opportunities for socializing and interacting with a variety of others, both within the school community and with the wider community. The strategy requires close meaningful relationships with adults who understand the whole child and are themselves bonded together in a team relationship that is a community of learners. The community should plan a variety of individual, small group and whole group learning experiences within a flexible schedule.

What kind of school building addresses the unique social, intellectual, physical and emotional needs of this age group? The older stacked egg crate format of the traditional school makes the operation of a best practices programme difficult, just as the same format can repress the spontaneous exploratory learning and need for community of the younger child. It is simply too inflexible, the very walls seemingly dictating a nineteenth-century form of education.

This is what the criteria developed by the National Middle School Association look like when translated into architectural features. The list ranges from the broad and general to the detailed and specific:

1 Educators committed to young adolescents Needed architecturally: the building must be fun and an exciting place to be, filled with colour and light. There should be provision for

places to hang out and with overlooks, places to see and be seen.

2 A shared vision

Needed architecturally: a planning process informed by the commitment and the vision of all the stakeholders The board, superin

tendent, principal as leader and informed faculty/staff, all participating, and ‘on board’.

3 An adult advocate for every student Needed architecturally: space for files, activity space for advisory groups to meet, involving all faculty and staff.

4 Family and community partnerships Needed architecturally: parents’ room, office, lounge, as well as community access to facilities such as the gym, the auditorium and the media centre.

5 Varied teaching/learning approaches, cultivating multiple intelligences, providing hands-on experiences, interdisciplinary, actively involving students in learning; a curriculum that is challenging, integrative and exploratory Needed architecturally: facilities to enhance the intelligences – music, art, drama, dance, film and video, out-of-doors, social spaces. Also required are classrooms of varying sizes and classrooms that permit varied activities; project rooms that are not necessarily science rooms; places to work and to be alone; places to accommodate a wide range of equipment.

6 Assessment and evaluation processes that promote learning

Needed architecturally: authentic assessment involves spaces to create, perform and present student work for evaluation.

7 Flexible organizational structures

Needed architecturally: provision for individual and team planning; team offices that are not departmentalized; team areas for kids, flexible spaces for flexible grouping; planning time and spaces to work that are not in the lunch room; teachers seen to be professionals.

8 Programmes that foster health, well-being and safety: comprehensive guidance services

Needed architecturally: alternatives to

corridor locker areas, instead student areas which communicate a sense of trust and safety; a clinic with a nurse; counsellors whose offices are located where the reason for going is not clearly evident, to encourage a relaxed view on the discussion of personal problems; nutritional planning in the cafeteria.22

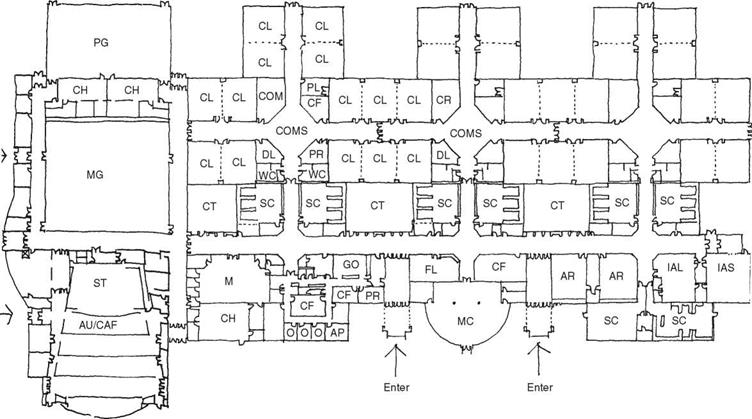

A number of these design and development criteria can be discerned in the floor plan of Central Middle School in Tinley Park, Illinois. Extensive consultation with all the users informed the process from the very initial planning concept right up to the construction of the building itself. Rejecting usual design strategies such as the ‘egg crate’ plan and the customary closed suite of departmental offices, Central Middle School accommodates the needs of students, teachers, administrators, staff, parents, and the community in an entirely different way.

Each of the three grade levels has a commons, around which wrap the classrooms. These accommodate 120 students in each grade. Immediately adjacent to the commons are the teacher workshops, conference rooms, project rooms, computer rooms, and bathrooms. Each grade level has its own science/project rooms. These are not so committed to advanced science that their furnishings exclude other kinds of projects. They are very flexible in use, a move carefully thought through by the faculty and the principal.

Each of the commons is large enough for all the children at that grade level to gather, sit on the carpets – each being a different colour according to the grade – and to discuss and plan together. Each commons leads not only to the other commons, but also to Main Street or central hall. This latter hall passes by the offices and special area rooms so when classes need to move to the art and music rooms, industrial arts shop, media centre, gym and auditorium/cafeteria, they can do so without disturbing a single other classroom.

The media centre, the auditorium/lunchroom, and gyms have outside entrances, making them accessible to the community during non-school

|

|

|

![]()

FL – Faculty eounge MC – Media centre AR – Art

IAL – Industrial arts lab IAS – Industrial arts shop

|

hours. Some classrooms between the commons are designated as ‘flex’ rooms to accommodate differing numbers of children in the grade levels; a room could be a seventh grade classroom one year if enrolment there were higher or an eighth grade classroom the next as that group moved on.

Conclusion

Tinley Park is not a wealthy suburb. What was in place as the building was being planned was a knowledgeable, experienced, and determined principal, supported by an equally knowledgeable superintendent, both of whom matched the criteria listed in This We Believe …And Now Must Act.21 They shared a vision for a middle school programme that met the needs of their constituency and they built a building that both reflects and facilitates that programme. This was in no small way down to the sensitivity of the architectural team responsible for the building.

Charity James puts it this way:

..when I speak of the need for schooling to be living, my language is deliberately value-laden. I believe that the living behaviours are to explore, to make, and to enter into dialogue, and that these are the ways members of a school should engage themselves.23

Other exemplary middle school buildings exist and, fortunately, are becoming more visible in those communities who have listened to principals, teachers, parents, members of school boards, and the adolescents themselves, all spokespersons for a way of teaching and learning that is truly developmentally appropriate.

The messages of these buildings, to and about the adolescent, are that he or she is understood and his or her many and even competing, even occasionally conflicting, needs are respected and accommodated.

However, children are not usually the ones who are planning the buildings they live in. They are, in

fact, the invisible clients. Perhaps three, six or even nine years of their lives will be spent in the building in question, yet they have no input into the design, iconography, uses, patterns or aesthetics of the building. It is therefore up to the adults in charge to develop what Thomas David calls ‘environmental literacy’.

The development of environmental literacy involves the transformation of awareness into a critical, probing, problem-seeking attitude towards one’s surrounds. It entails the active definition of choices and a willingness to experiment with a variety of spatial alternatives and to challenge the environmental status quo. Old roles, which were characterized by submission, or apathy or dependency on the ‘experts’ to determine one’s environment, must be unlearned.24

If, as Robert Sommer says, ‘A design problem is a value problem’ and the question is ‘Whose interests are to be served?’, how do we better serve the interests of children?25 What do we really want to say to them? Their buildings and what goes on in them communicate, whether that is our intention or not, where they stand in the wider world. Do we want to communicate to them that they are not worth safe, well-maintained and child- and adolescent-friendly buildings, rich in beauty, interest and opportunities for engagement? Or do we want to communicate to them, overtly and symbolically through the built environment, that they are to be inspired, trusted, respected, loved, protected, and understood in all the developmental aspects of their being? If so, we will help them live in model homes, complete communities, and embryonic democracies. If we don’t, we have made choices that are, in the words of John Dewey, ‘narrow and unlovely’ and we put our very democracy at risk.