In the United Kingdom, an estimated 50 per cent of school children bring packed lunches for their midday meal, a far lower proportion than elsewhere in Europe. An unknown number of children take food to school in the form of snacks of variable nutritional value. A packet of crisps can be consumed on the way to school, as a substitute for breakfast. According to a recent survey, 40 per cent of children have, by way of breakfast, a chocolate bar or a packet of crisps on the way to school.52 Crisp packets turn up again as plastic pencil cases and holdalls. Certainly in Britain, where packet crisps were invented during the 1940s, the primary school classroom and wider environment can almost not be envisaged without the ubiquitous crisp packet.

Often, the crisp packet accompanies the lunch box which often, in the UK at least, is a contested and emotive object in a child’s life. In the territory of the lunch box, conformity and competition are powerfully combined. Never merely a container, the latest fashions, trends, TV heroes, ‘must have’ toys or status symbols are coated in plastic on the boxes designed for the younger child. Not only the shape and outer design of the box, but its contents, usually express conformity. In the UK, it has been noted that a child may suffer bullying as the result of a non-conformist lunch box.

There’s a lot of pressure from other kids to have the right kind of ready-prepared food, and anything homemade is terrible. I’ve seen shocking teasing when other kids see what one child has in a carefully prepared lunch box: they show no mercy!53

Official concern over the content of lunch boxes was evident in the early years of the twentieth century. Children who walked long distances to school often carried food for the midday meal with them, since they were not able easily to return home. In 1905, the Inter-Departmental Committee on Medical Inspection and Feeding noted ‘The lunches brought by the children were generally of a most unsatisfactory nature’54 and suggested these should be supplemented by hot soup or cocoa.

Almost a century later, official concern with the contents of lunch boxes is, outside of the Scandinavian countries, nonexistent. However, there are local initiatives that have attempted to influence the content of packed lunch boxes and raise awareness in general of the importance of the portable edible landscape. Teachers at Edgware Infant and Nursery school near London decided to intervene and attempt to raise awareness of the poor nutritional contents of food brought to school by very young children. There were cultural issues identified, as some of the diverse backgrounds of the children did not contain any tradition of packed food. The starting point in raising awareness was an exercise of drawing the contents of the lunch box and labelling the items. After a series of community workshops and practical sessions, the pupils were asked again to draw the contents of their boxes. The differences were reported to be ‘staggering’.55

In Iceland, food skills and home economics are high status subjects in the National Curriculum from the age of six. Here also, the school building is sometimes used on a shift basis to host early years education in the morning and later years in the afternoon. The younger children bring with them a box or food bag containing a mid-morning snack. Without any official policy or statement there is a universal understanding among the school community and parents about what is acceptable content. This practice is strengthened by the sponsorship of a dairy company who supplies children with the food containers. ‘For many years all 6-year-old children get a plastic box for their provisions from home, along with a ruler, eraser and a timetable when they start at school in August. A letter is included to parents where we use an official propaganda to point out the necessity of healthy eating.’56

Here, conformity is ‘cool’ and seems to be generally accepted. Usually children will bring a sandwich and it is expected that the bread will be wholesome. Any drink will either be water or milk and a piece of fruit is most usual. Strictly frowned upon is any sweet, chocolate or fatty food such as crisps and a child who brought such content to school would be looked on by his or her peers as an unfortunate – quite the opposite of what happens in the UK. Parents expect schools to be places where good food is consumed within a pleasant environment.

Where children do stay at school to eat a hot meal, the cost is subsidized so that parents pay only thirty per cent of the cost. A traditional family type meal is served consisting of meat or fish with vegetables and a drink of milk or water. No sweet or desert follows. Teachers always eat the same food alongside the children on a rota basis and this is a valued and paid activity within the educational system.

Children and young people have traditionally carried food with them from home to school for lessons in cookery. Now labelled ‘Food Technology’ in the UK National Curriculum, the word ‘cooking’ does not get a mention. This explains partly the

|

|

emphasis on ‘cooking’ and ‘making’ food rather than its design, production and marketing that fuels the ‘Focus on Food’ campaign which was initiated in 1998.

Not every school has space or equipment enough to teach food preparation and cooking

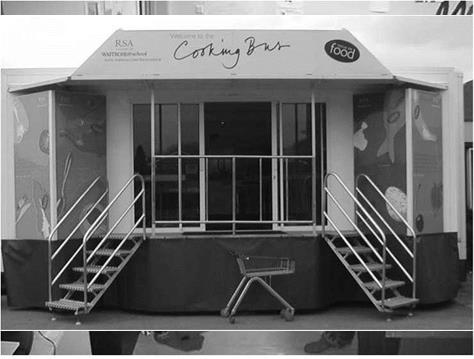

skills and often, especially in primary schools, the general classroom is used with the aid of microwave ovens. The Royal Society for the Arts’ Focus on Food campaign has recognized this and a portable kitchen, or Cooking Bus, is a design feature of this initiative which works to encourage interest and

pleasure in cooking and to have the subject made a compulsory part of the national curriculum. The Cooking Bus is sponsored by Waitrose supermarket and travels the length and breadth of Britain stopping at schools or supermarkets for a week at a time. It comes supplied with experienced teachers, ‘state-of-the-art’ equipment and food supplied by Waitrose. When opened up the bus becomes an impressive teaching kitchen for up to sixteen children who are, in stages, all shown how to make a meal or a range of dishes, usually representative of a particular culture or region. After cooking the food, the children then sometimes sit down together and eat it.57

The Cooking Bus, unlike most children’s home kitchens, is a highly serviced, pristine environment. Food ingredients appear, as if by magic, often still packaged from the supermarket and otherwise arranged already weighed out in attractive containers. There is an air of the TV cookery show about the space. Although basic skills are taught, for older children at least, little emphasis is placed on the slow work of acquiring, preparing and assembling ingredients. This is done by others before the children enter the bus. Washing up is done by adult assistants and the pupils have a rare experience of cooking at ease. It is fast and effective. Vegetables, fruits and herbs are presented as beautiful objects, the lighting and wall mirrors seem to enhance the natural colours of the ingredients rather as they do in supermarket outlets. The teacher emphasizes the quality of equipment as necessary in order to cook well. The utensils are provided by the John Lewis partnership of which Waitrose is the principal food branch.

After cooking in Waitrose-branded plastic overalls, at the end of the session the pupils are supplied with branded foldable cardboard containers in which to carry their produce home within a branded plastic carrier bag. The teacher’s plastic overall is branded ‘Savoy Educational Trust’, a branch of the well-known, high quality London hotel which provides funding for the teachers’ salaries. But will cooking at school ever be the same again? The Focus on Food campaign hopes so and does its best towards this aim by means of inservice teacher training held in the bus and by leaving behind its colourful, glossy Food Education Magazine, free to all registered schools. Inside the magazine, celebrity cook Gary Rhodes demonstrates how to make pastry and the reader is directed to the Waitrose website for more ‘curriculum connections’. The Cooking Bus is on the road for forty-eight weeks of the year and the project relies totally on large amounts of corporate sponsorship which are secure for the immediate future. The UK supermarkets are in intense competition with one another and each must find its marketing niche in relation to education in the pursuit of brand loyalty. Research carried out by academics at the University of Reading in England will report on the effects on children of sustained education around food. Clearly, the effect of sustained educational activity on the wider community is something that the supermarkets are prepared to gamble will pay off.