Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the present surge of interest in play and playgrounds is why this should have become an issue. Within months, two different government departments have produced closely focused reports, each related to the New Opportunities Fund (NOF), Barnardos have funded a three-year ‘Better Play’ programme, the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA) has issued a new report and the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) is developing an initiative.7

A number of simple answers are suggested. The Government, in the run-up to the 2001 election, pledged £200000 000 for improving children’s play opportunities and is now soliciting advice and applications for funding to enable the money to be spent wisely. Long-term neglect of play facilities nationally is evident in almost every community and so current need is plainly matched to future funding. More important, there is growing awareness of the health and social costs of an increasingly obese society, which might in part be derived from inactive ‘couch potato’ children.8 Rightly or wrongly, there is a perception that better designed and safer playgrounds might help to counter this by encouraging more children to engage in active, outdoor play.

The Office of the Deputy Prime Minister’s earlier report on environmental issues (ODPM 2002) also singled out play spaces, and especially play space for children with disabilities, as needing guidance and funding. The implications for children’s play space of the Disability Discrimination Act, fully implemented in October 2004, has been relatively neglected until recently, so that children and carers with disabilities have had little specific consideration.

There is a need to explore ideas such as those contained in the Office of the Deputy Prime

Minister’s guide, notably the suggestion that play area providers might allocate staff to supervise children at fixed points in the day.9 The case for play leaders appears to be well made here and the subsequent proposals of the Children’s Play Review report Getting Serious About Play, which includes specific funding proposals, makes it appear realistic.10

The linkage between the quality of play, the frequency of accidents and the degree of supervision of young children is beyond question and so the distinction between supervised and unsupervised play space is of interest here. The age, size, condition and location of play apparatus all have a bearing on safety but only rarely can individuals or advocacy groups have a significant influence on these issues. On the other hand, effective supervision and guidance can reduce the effect of unsuitable locations or choices already made, without inhibiting children’s freedom to play independently and constructively. Aggression, wilful damage and unsuitable dress or demeanour, unavoidable hazards in public space, can also be confronted by an active supervisory presence. At its simplest level, supervision provides the possibility of rescue and first aid as necessary. In Germany it is unlawful to allow unsupervised children under the age of three on playgrounds. In Britain we appear content to incorporate special elements within our version of the European standards to address the risk attached to this situation. Vandalism is always a potential issue when play areas are equipped with items less robust than well-secured multi-play units – and even they can never be wholly secure – but supervision, coupled with an active community interest, can go some way towards limiting these problems.

There is undoubtedly more to children’s safety and community well-being than swings and roundabouts, since the location and management of the playground in a time when drive-by shootings, muggings, stalking and stabbing incidents are reported regularly in the press may be seen as a social order as well as a health and safety issue. The political thrust is, then, to improve the quality of life of the whole community.

|

|

|

|

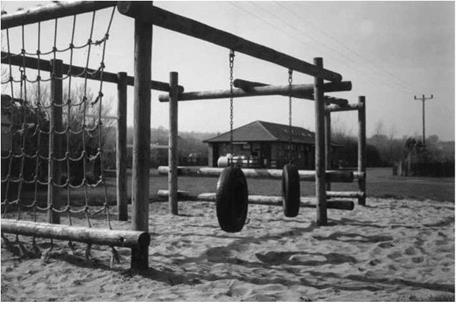

1 There are numerous head and other entrapment points in the structure. Low/medium risk.

2 The ramp is at a greater angle than the maximum permitted 40°. Medium risk.

3 There is an absence of sufficient and appropriate guard rails, handrails and other support and access aiding features. Medium risk.

4 The side and bottom structural sections invite climbing and perching. Low/medium risk.

5 The item fails grip/grasp requirements. Low risk.

6 Accessible height is in excess of three metres. Medium risk.

7 The impact attenuating surface in place around the platform is inadequate. Medium/high risk.

As a part of an inspection report in 2003 a registered inspector said that ‘this item has no place in or near a playground for young children since, while falling short of being dangerous, it is certainly high risk’. Remedial work has been undertaken but another inspection company was awarded the inspection contract in 2004.