The 1988 Education Reform Act heralded the introduction of the National Curriculum for all children of compulsory school age.24 The National Curriculum sets out learning objectives and attempts to provide coherence in the teaching of pupils, whilst also clarifying the role of teachers within the classroom. The following four criteria summarize the government’s key ideological aims:

– to establish entitlement to a number of areas of learning for all children irrespective of their social or ethnic background. In particular it seeks to promote the development of people as active and responsible citizens.

– the National Curriculum makes expectations for learning and attainment explicit and establishes national standards for the performance of all pupils.

– it promotes continuity and a coherent national framework that ensures a good foundation for life long learning.

– it promotes public understanding providing a common basis for discussion of educational issues among lay and professional groups.

In reality, its introduction was a rather desperate response to the perceived failure of education during the 1970s and early 1980s. Students were emerging from the system with very poor social and literacy/numeracy skills. Politicians felt they had no control over what was happening and sought to disguise the general underfunding of the system in the cloak of new educational strategies. The need for new and refurbished schools was largely ignored at that time. Significant government funding has only come on stream since 2001, and this is largely directed towards secondary schools rather than primaries. However, it is fair to say that most primaries are receiving more resources, improvements to the maintenance and repair, and additional classrooms to support community links (ICT training suites which can be used outside school hours), early years facilities (nursery units) and after school clubs. Although the National Curriculum does not refer to the environment specifically it is possible to interpret the spatial implications of its content.

The related framework of the National Literacy and Numeracy Strategies contains detailed guidance about planning and teaching from which spatial issues can be ascertained. It is important to understand the key ideas of the curriculum and how these are put into effect in the classroom, which in turn will help to identify the architectural requirements of the classroom’s design, now and in the future.

There have been some significant developments in primary education in recent years, due to legislative changes to make the National Curriculum more effective. The early stages of its implementation were problematic; most teachers found it difficult to cope with the large subject content they were expected to cover. A period of review led to a reduction in the amount to be taught in most subjects and the introduction of a proscriptive element of time to be spent on certain subjects over and above others. Recent modifications to the National Curriculum, including the introduction of the National Literacy and Numeracy Strategies and the evolving of ICT (information communications technology) into a separate dedicated subject within the curriculum, have had a positive effect on education and its delivery, requiring a new approach to the design of schools. The numeracy and literacy strategies for primary schools give guidance ranging from how each individual minute of classroom time should be used to the arrangement of classroom furniture.

The government has taken control over not only the objectives, but also the teaching methods.

The National Curriculum Handbook for Primary Teachers in England (1999) identifies three core subjects: English, Mathematics and Science. In addition to these, there are seven non-core foundation subjects: Design and Technology; Information Communication Technology; History; Geography; Art and Design; Music; and Physical Education.25 For each subject and each key stage, programmes of study set out what pupils should be taught, and attainment targets establish expected standards of pupil performance. National frameworks for literacy and mathematics are published by the Department for Education, and exemplar schemes of work are jointly published by the DfEE and QCA; they illustrate how the programmes of study and attainment targets can be translated into practical, manageable teaching plans.

The National Curriculum identifies six skills areas, which are described as ‘key skills’ because, according to government dictum, they help people of all ages to improve their learning and performance in education, work and life (DfEE and QCA, 1999:20). These skills are: communication, application of numbers, information technology, working with others, improving learning performance and problem solving. In addition to these key skills the National Curriculum identifies five thinking skills which complement the key skills. These are: information-processing skills, reasoning skills, enquiry skills, creative thinking skills and evaluation skills. This provides a theoretical justification for the core subject areas, as they are thought to encompass knowledge, skills and understanding without which it is not possible for other learning to take place effectively.13 The National Curriculum Programmes of Study set out what pupils should be taught in each subject and provide a basis for planning schemes of works. The programme of study sets out two areas of benefit: [5]

which the knowledge, skills and understanding should be taught.26

For example, the skills of speaking (from a text) and writing are viewed as fundamental aspects of English as a core subject taught at both Key Stage 1 and 2. The Programme of Study for English states that:

In English, during key stage 2, pupils learn to change the way that they speak and write to suit different situations, purposes and audiences. They read a range of texts and respond to different layers of meaning in them. They explore the use of language in literacy and non-literacy texts and learn how language works. Speaking and listening: during key stage 2 pupils learn how to speak in a range of different contexts, adapting what they say and how they say it to the purpose and the audience. Taking varied roles in groups gives them opportunities to contribute to situations with different demands. They also learn to respond appropriately to others, thinking about what has been said and the language used.27

The National Literacy Framework for teaching sets out teaching objectives for Reception to Year 6 to enable pupils to become fully literate. Literacy unites the important skills of reading and writing. It also involves speaking and listening, which although not separately identified within the framework, are an essential part of it. The National Literacy Strategy contains detailed guidance on the implementation of literacy hour, in which the relevant teaching will take place. The Literacy Hour is designed to provide a practical structure of time and class management which reflects the overall teaching objectives (a step by step guide is included in Appendix A). The National Literacy Strategy defines the structure of the literacy hour quite precisely. It should include the following:

a. Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2: Shared text work, a balancing of reading and writing. (Whole class, approximately 15 minutes)

b. Key Stage 1: Focused word work. Key Stage 2:

A balance over the term of focused word work or sentence work. (Whole class, approximately 15 minutes)

c. Key Stage 1: Independent reading, writing or word work, while the teacher works with at least two ability groups each day on guided text work, reading or writing. Key Stage 2: Independent reading, writing or word and sentence work, while the teacher works with at least one ability group each day on guided text work, reading and writing. (Group and independent work, approximately 20 minutes)

d. Key Stage and Key Stage 2: Reviewing, consolidating teaching points, and presenting work covered in the lesson. (Whole class, approximately 10 minutes).28

The literacy hour offers a structure of classroom management, designed to maximize the time teachers spend directly teaching their class. It is intended to shift the balance of teaching from individualized work, especially in the teaching of reading, towards more whole class and group teaching.

The essential elements of the literacy hour are: shared reading as a class activity using a common text, e. g. a big book, poetry poster or text extract. At Key Stage 1 teachers should use shared reading to read with the class, focusing on comprehension and on specific features, e. g. word-building and spelling patterns, punctuation, the layout and purpose, the structure and organization of sentences. Shared reading provides a context for applying and teaching word level skills and for teaching how to use other reading cues to check for meaning, and identify and self-correct errors. Shared reading, with shared writing, also provide the context for developing pupils’ grammatical awareness, and their understanding of sentence construction and punctuation. At Key Stage 2 shared reading is used to extend reading skills in line with the objectives in the text level column of the framework. Teachers should also use this work as a context for teaching and reinforcing grammar, punctuation and vocabulary work.

At both Key Stages, because the teacher is supporting the reading, pupils can work from texts that are beyond their independent reading levels. This is particularly valuable for less able readers who gain access to texts of greater richness and complexity than they would otherwise be able to read. This builds confidence and teaches more advanced skills which feed into other independent reading activities.

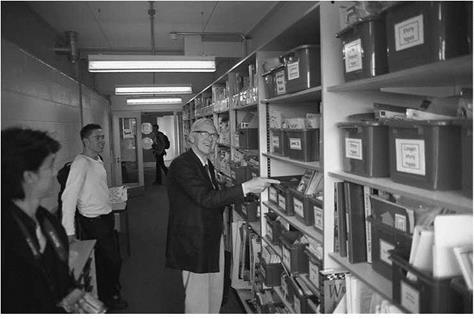

We have quoted at some length from the National Curriculum (in one core subject only), in order to give the reader a flavour of the tasks and functions which need to be considered when designing a classroom. The way in which the classroom is organized affects the extent of each child’s contact with the teacher and the opportunities for effective learning. A functional, well-organized classroom will have teaching materials, tools and equipment arranged efficiently so that they are easy to find, use and keep in order. The planned layout of an activity area should match the intentions of the activity, with resources in close proximity. As will be seen in later sections, the space standards recommended by the Department for Education are, in my view, inadequate for many classes, particularly where pupils have a high level of special educational needs. That is why all aspects, such as storage, become critical. There should be a definite place for everything and storage should be labelled appropriately, making it easily accessible. Children’s personal storage should be allocated a particular place which is secure, yet positioned so that it does not obstruct learning and spatial efficiency. This will enable children to be given responsibility for taking out and putting away their own materials and equipment. Materials should also be stored at appropriate levels, so that access to certain equipment can be controlled by keeping it out of reach of pupils.

There is very often surplus equipment and resources lying unused in classrooms. The development of Information Technology resources in schools is essential for every pupil, to contribute towards the development of other curriculum themes, skills and personal qualities. Grouping such resources and sharing them between selected classrooms would usually be more efficient and economies could be made in the provision of

|

|

specialized equipment and resources, such as a shared information technology suite. The pairing, or grouping, of classrooms enables flexibility in areas such as the sharing of practical areas, allowing teachers to work together or separately as and when required, with a variety of different teaching group sizes this flexibility enables.

Primary classrooms should not simply provide a neutral space for teaching and learning, but should also communicate to children something about the ethos of their education, what is being offered and what is expected from them as pupils within the school community. An ordered spacious environment gives them a natural sense of wellbeing, however, other features, such as the use of colour, the controllability of their environment, and good acoustics will all help to communicate essential messages. The Government wishes to see schools designed to a standard ‘comparable to that found in other quality public buildings, to inspire pupils, staff and parents’.29 This means that a far more sophisticated array of design skills needs to be brought to the table for discussion with future users, especially teachers. Space in classrooms is always limited; yet the space that is available must be utilized in such a way that a wide range of

activities, which form essential elements of the National Curriculum, can occur simultaneously. This is some challenge.