The following sections describe five projects that I have been involved with that concern landscapes

created for children at childcare centres and schools. Each project is an experiment and a discovery for myself and the people involved in their own landscapes. What I describe here reflects only one perspective of the process required to create landscapes for children, and this is the view of the designer. There are other voices that are vital to the design process that include the children, parents, collaborating designers, administrators, maintenance staff, unions, and school boards. I am greatly indebted to the individuals and groups that have made and are making these landscapes possible.

In North America, elementary school-aged children spend up to two hundred days per year at school, and approximately two hours of the school day are spent outdoors in the playground or play fields.6 With the increased use of childcare centres (often located next to or inside the school) for supervision after school, the playgrounds at schools and child centres have become a substitute for the backyards of a previous generation. This situation places an unprecedented importance on the nature of the schoolyard and what it has to offer children.

Historically, most outdoor play environments at schools and childcare centres have been assigned

|

Figure П.2

Figure П.2

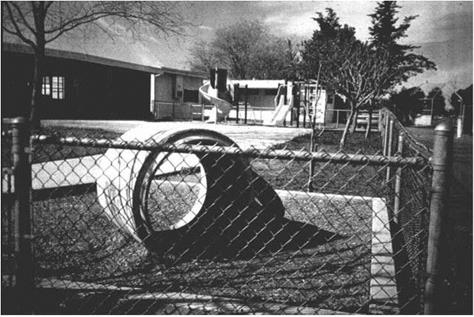

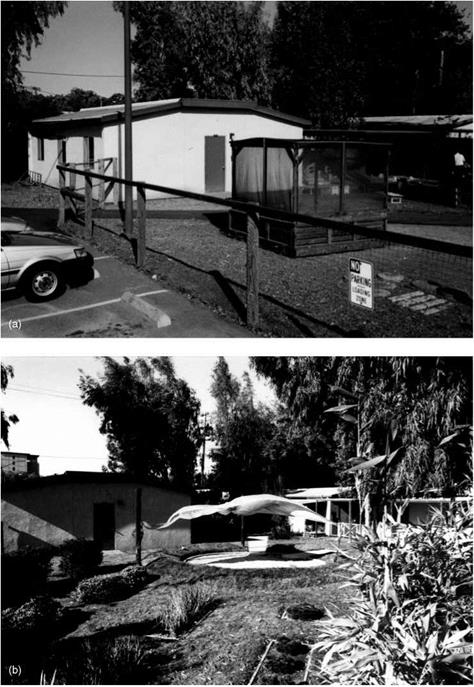

(a) Previous infant play yard at UC Davis.

(b) Infant Garden at UC Davis. (Photos: Susan Herrington.)

the role of providing a space for physical exercise. This tendency to associate playgrounds with physical development can be traced back to nineteenth-century social programmes in Europe and North America. The yards that surrounded

nineteenth-century urban schools provided not only open space for calisthenics, outdoor gymnasium structures, and formalized games, but an important remedy for physical and mental degradation: sunlight and fresh air. The gymnastic

|

structures would prove to be pervasive in symbolizing play in the outdoor environment. The fabrication of these structures coincided with the development of production-line industries. The prefabricated slide could be manufactured as readily as the average domestic appliance. By the twentieth century, outdoor play spaces for children in North America meant spaces that contained prefabricated play equipment.

But what else might external play environments, the landscapes designed for children, offer besides play equipment and sports fields? The material qualities of landscape offer a rich source for imaginative events. Animals live in the landscape, it is rained upon, it floods, big winds blow through it, the sun rises and sets, and snow falls. Small changes can help illuminate the idea that the landscape is a dynamic living system. Another dynamic aspect of landscapes found at schools and childcare centres are the children themselves. In one school setting you might find children ranging in age from infanthood to pre-teens. How can outdoor play spaces at schools begin to address the needs of such a wide range of age groups? How can

landscapes that were originally designed for school – aged children begin to address the developmental milestones of the newest users of the schoolyard, namely infants?

These questions are at the heart of the Infant Garden project in Davis, California. The Infant Garden was created for ten infants enrolled in the Child and Family Study Center at the University of California. The project involved the retrofit of the centre’s existing 4000 square feet infant play yard. Like the exterior play spaces found at many childcare centres for infants and toddlers, the existing yard was viewed as an outdoor floor space where play structures and play equipment were brought outdoors from the inside. The primary goal of the Infant Garden was to create an outdoor play landscape that would support the sensorimotor and socio-emotional development of infants as it occurred in spontaneous exploration.7

The University Child and Family Study Center is a laboratory where university students and teachers study the enrolled children and analyse their developmental progress. The various age groups (infant, toddler, preschool) were allocated

spaces in a series of one-storey modular buildings in a campus-like setting. The university students were encouraged to manipulate the physical arrangements of the interior spaces to see how these changes influenced specific developmental abilities of the children. Furniture was moved, lights changed, or colours were added to surfaces by the university students; thus, the students and staff were very accustomed to changing their space. The design team involved myself, the director, assistant director, and other child development specialists and staff members. After my first meeting with the team, I quickly realized that infants were a unique subculture among adults and older children. When we began to consider modifying the infant’s outdoor environment as an extension to the experimental setting found inside, the idea of designing the yard as a space to observe specific developmental milestones emerged. Like the requirements that might serve to organize and shape the space of an adult landscape (such as sitting and eating lunch, waiting for a bus) the developmental markers of the infants guided the creation of spaces and surfaces in the Infant Garden.

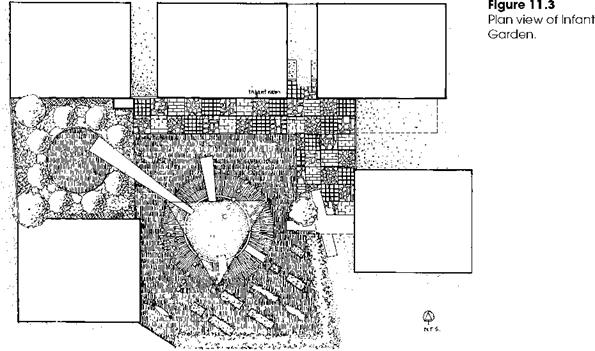

This approach opened a wide range of design considerations that went beyond the usual design requirements for playgrounds which typically involve the placement of a chain link fence, equipment and rubber matting. We thought of the yard as a garden where simple landscape elements such as earth, plants, stones, and sand would provide a rich source of loose parts and an ever – changing space for experimentation by the students and children. The primary features of the Infant Garden included a central earthen ring that contained a sand area at its centre and was shaded by an adjustable parachute canopy; a trail of stepping stones that enticed infants out into the yard; a pine circle that was planted with a variety of plantings where the infants could explore on their own; and a maze area comprised of five different plant species, all edible.

Our project became part of a comparative research project by Sarah Jane Neville, Dr Carol Rodning, Kay Jeanne Gaedeke, and Dr Larry Harper. They studied the play yard prior to construction and four weeks after construction

|

|

Figure П.4

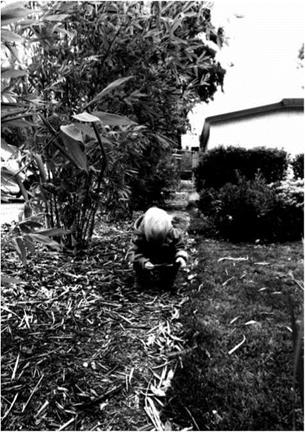

Plant parts as play props at the Infant Garden. (Photo: Susan Herrington.)

of the Infant Garden to observe if the infants’ use of the same site with two different physical environments was quantitatively different. The researchers found statistically significant differences between the use of the previous play yard and the garden. In the Infant Garden, the extent of spatial exploration increased, meaning that the children explored more of the yard, an action connected to cognitive and physical growth. The types of motor manipulations were more complex and varied, indicating that the infants were challenged to do more physical actions. The amount of associative play with student care givers became more intense, meaning that their social and emotional skills were engaged in the use of the garden. Finally, the number of times infants played with natural loose parts, namely leaves, twigs and flower heads, increased, augmenting the opportunity for fine

|

|

motor development (the use of the fingers, hands and mouth).

The Infant Garden prompted me to ask how we might design children’s outdoor play environments that address the breadth of developmental milestones, i. e. social, emotional, physical, and cognitive. Additionally, a major component of the Infant Garden was the introduction of plant material to the play space. This also raised questions about the potential of plant material and other landscape elements. Plant material and other standard landscape items are relatively cheap when compared to the price of play structures and rubber matting. Could the use of plant material alone begin to add to the variety of developmental opportunities a play yard provides?