Arguably, it is therefore important to maintain and reflect the character of the landscapes in the design of facilities and artefacts, while providing many functions that are the same as those needed at home, as well as reinforcing the contrast between the city and the more natural landscapes of the outdoors.

However, it is possible to develop designs that are more redolent of the stylized settings of Tolkien or Disney than those reflecting the real qualities of nature. This must be avoided, as must all forms of pastiche or superficial imitation, in favour of honest, robust, simple, unobtrusive designs, which serve to provide their function with the minimum of fuss. These must not upstage the greater landscape setting that people have come to enjoy.

At this point we can return to the Recreation Opportunity Spectrum (ROS) described in Chapter 1. This helps us to define the type of landscape setting and the most appropriate approach to facility and artefact design. In some locations the correct solution is no facilities, no artefacts, and only repair to physical damage. It is crucial to develop a modest approach, and to resist the need to make grandiose statements or to follow a

|

|

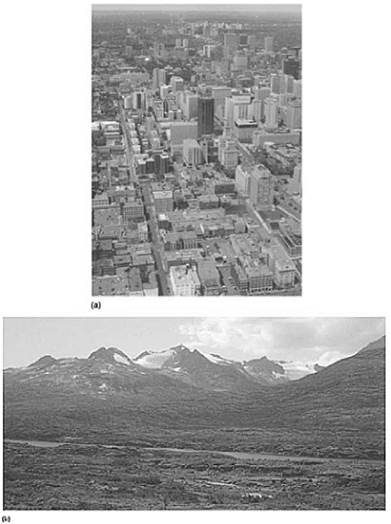

(a) A city view where human activities and structures dominate. The plan is based on a geometric grid, the buildings are rectangular, and the whole is tightly controlled, as are traffic movement and the regulation of peoples’ lives to some degree by timetables. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. (b) A remote, uninhabited wilderness area, untouched by direct human activity. The mountains, glaciers and hard climate dominate. It is possible to wander freely and feel far from the urban world; to obtain solitude; and to use the skills of selfreliance when facing natural hazards. Alaska/Yukon border, USA/Canada.

flamboyant style more suited to pretentious office developments.

The correct approach is epitomized in many ways by the 1930s designs of the US National Parks Service, which used natural materials in a sturdy, simple way, reflecting their settings very well. Some later designs were overly ‘trendy’, and have become very dated as a result.

|

A design for a shelter, taken from the design manual prepared for the Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Parks Service of the USA in the 1930s. The style is simple and robust, and uses materials as close to their natural state as possible: round logs, wooden shingles and rough stone all left to weather naturally. |

The succeeding chapters will concentrate on the design of facilities and artefacts, but as a broad concept it is relevant here to consider the types of materials that might best suit use in the outdoors. Without doubt, a fundamental criterion should be to use as much local material as possible. Stone is best in rocky landscapes; timber is appropriate, especially in forests, but also in most other places. Artificial materials such as plastic, concrete or stainless steel are not always out of place, but should be used with care in small amounts for particular purposes in relevant locations such as rural and urban settings, or associated with buildings, particularly their interiors. Some materials will work when least expected. Plastic-coated profile steel (a modern version of corrugated iron) works surprisingly well as a roofing material, usually in a range of dark colours. Dull iron or weathered, galvanized or ‘Corten’ controlled-rusting steel does not look out of place in the countryside, and can be a useful protection against vandalism.

The use and appropriateness of various materials for use in the outdoors are best explored using a couple of examples. The visitor centre at Glenveigh National Park in Ireland, recently constructed for the Office of Public Works (OPW) to the designs of Tony O’Neill, offers some interesting contradictions. The setting is a majestic, bleak, barren, windswept, empty valley amongst dramatic bare mountains. The narrow public road that takes the visitor there passes through a similar, virtually uninhabited landscape for some miles. In order to respect the character of the landscape, the concept sensibly places the building low down amongst the landform, so that it barely impinges on the view. The building is composed of a number of circular concrete pods, and is roofed in turf, thus becoming almost a part of the landscape. It houses information, displays, toilets and offices to service the many visitors who come there, and acts as a gateway to the park.

The design of the external layout incorporates many elements that are somewhat urban

in form and material. The use of black tarmac surfacing, concrete kerbs, paving setts and steps and tubular metal handrails is questionable in the landscape setting. All these artefacts would be completely at home in an urban park but probably not a wilder setting such as that found at Glenveigh. There is little of the contrast that would otherwise mark a distinct change in the experience from that of city or managed landscape to that of this wild area. What is accomplished in the architecture is less happily continued into the external treatment.

At the heart of all design concepts where we want the landscape to remain dominant is the need to identify and respect the genius loci, the spirit of the place. This intangible quality is what makes places individual and special. It is what marks them out in the first place, and what makes them attractive to visitors. The designer must take pains to identify the genius loci and use it as a source of inspiration. It must also be respected and not compromised by the facilities created to allow visitors access and to protect the site.

An example of the genius loci’s being overlooked is at the Athabasca Falls on the Athabasca River in Canada’s Jasper National Park. The waterfalls are dramatic, and have a strong attraction for visitors on a river that flows through some of the most majestic scenery in the world: the Rocky Mountains. The park is accessed along the Icefields Parkway, and a side loop from this road takes visitors to the falls as an incident along the route from Jasper to Banff. The waterfalls have cut through the horizontal layers of rock to form a ravine. Instead of providing a path to a lookout point to see the falls, a complex and monolithic series of steps, ramps and a bridge have been constructed. Their size is too large for the landscape, and they are of a very urban construction and finish. Although providing barrier-free access, the structures seriously harm the genius loci of the falls. Even though the location, being close to the parkway, is intended to be accessible for all visitors and is therefore ‘roaded natural’ in ROS terms, such treatment is out of all proportion to that which is appropriate. It would not be difficult to dismantle the structures and restore the landscape to its former glory, as well as providing more sensitive access.