William Latham studied art at Christ Church, Oxford, and print media at the Royal College of Art in London. Between 1987 and 1994 he worked as a “visiting artist” at the iBM UK Scientific Centre in Winchester, where together with the mathematician Stephen Todd he developed his artistic style.

The works evolved during this time form the basis for an aesthetic that is known today as “Organic Art”, which serves as a model to many artistic artworks. Characteristic of his style are repetitive structures, in which simple geometrical primitives such as balls or tori are repeatedly joined, and, by iteration of geometrical transformations, such as rotations or translations, generate complex organic-appearing structures. His computer sculptures remind us of anemons, lobsters, shells, and of simple organic life-forms. Latham is frequently named in connection with the interdisciplinary area “Artificial Life”, in particular since he used an important technology for generating his picture contents: computer-aided evolution.

Latham developed his first system for generating forms before his first encounter with the computer. During his studies at the Royal College of Art, he became interested in the successive changes of form, and he developed Form – Synth (see [113]), a rule system for the modification of forms. On a given form, for example a cone or a ball, successive transformations such as beak, bulge, scoop, union, twist and stretch are fitted. Since several operations can be applied to the form, theoretically, infinitely many forms can be derived. Latham, quasifunctioning as a human machine, executed the instructions for modification on paper, and then generated the drawings. Some of these drawings were more than 10 meters high, and were filled with decision trees for forms that were even partly downsized with a photocopy machine, so that more room could be won for new forms [28].

Although he executed the forms created in this way also physically in plastic and wood, he believed the actual value to be in the enormous form potential of the systems. “He realized that the FormSynth system defined an infinite world of predefined form, which the artist explored to reveal only a selected few” [219]. With the title “The Evolution of Form”, a drawing produced in 1984, the thought metaphor was established for the future.

At IBM in Winchester he had access to computers since 1987, and he worked there with Stephen Todd and his team on the implementation of FormSynth for the computer. The best-known result is the program “Mutator”, developed until 1990 in the graphic programming language ESME1.

1 The extensible solid model editor is a programming language developed by IBM designed for the programming of CSG (constructive solid geometry) editors. Those editors allow, aside

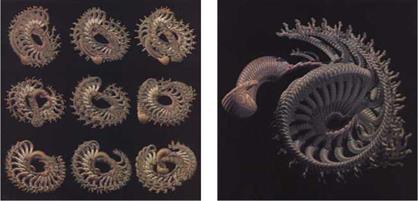

Mutator permits the user to navigate interactively in the parameter space of an algorithmically given structure, and also to apply operations such as mutation and selection to exploit the space of possible forms. From each genome in Mutator, eight variations are produced in one step, and are represented together with the initial form in a matrix of nine forms (see Fig. 12.1). One form is selected, parameters for the mutation are adjusted, and the process runs again.

|

(b) |

|

Figure 12.1 (a) Small hand-drawn FormSynth tree; (b) three “Mutator” frames (Courtesy of William Latham) |

![]()

|

Thereby the mutated genome corresponds to the parameter set of a base program that was created in the programming language ESME. The base program was adapted manually by Latham for each new mutation family. It applies certain complex functions, such as building horns, branches, and ribcages, over and over again, which explains the aesthetic consistency of his pictures.

The horn function distributes geometrical primitives along iterated geometrical transformations. Gradually applied rotations around space axes (twist, bend) and translations (stack, side, bake) supply results that often remind one of the horns or spinal columns of higher organisms. The function “branch” produces a pattern similar to phyllotaxis according to the algorithm described by Vogel (see Sect. 3.4).

The use of the function “ribcage” lets two equal geometries develop, reflected symmetrically along an axis, which, in combination with the “horn” function, resemble ribs that are arranged along a spinal column. These functions can call themselves or other functions, and in this way produce recursive, self-similar or highly complex combined structures.

The root program is termed by Todd and Latham a “structure”, the number of the forms derivable from a structure in Mutator is a “family of forms”. The parameter vector of a family is changed by Mutator in a mutation step according to given rules; it corresponds to a genome. Information is added to the once-produced root program, such as which parameters of the functions may be changed by Mutator, and within what limits they may move.

from the combining of primitives, also their iterative multiplication, and include commands for the programming of user interfaces.

Chapter 12 For humans it is analytically no longer determinable what is the visual result Media Art of just one of the above-named functions with a given nontrivial parameter set.

Only if the computer shows the computed picture, do split up, straight, chaotic, curved, accumulated shapes become visible. With large parameter changes the pictures offer again and again new surprises.

Although Latham’s work and the resulting art are often used for illustrations of “Artificial Life” due to their visual proximity to living organisms, Latham’s motivation is an aesthetic one. Though his pictures and the selected method refer to similar processes in nature, he developed his “own vision of nature”. However, here he is neither concerned with the simulation of biological processes, nor with the production of animated structures in the sense of artificial life.

![]()

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

He uses the evolutionary process because it produces surprising results, which, with the help of supporting software, can bring about what are to him interesting visual views. Latham has aimed at finding interesting forms in a potentially unlimited, deterministic, organic realm of forms as quickly as possible. Todd

and Latham developed different techniques in order to not blindly hunt around in the space of possible forms. Their goal was to adjust the produced forms to the whishes of the users, and thereby specifically to work out an interesting form once it was found. Using these techniques, the computer becomes an intelligent coworker that suggests forms, something that once could never have imagined.

■ Evaluation of Generated Forms

Each of the nine forms represented in one step can be evaluated. The evaluation is stored and serves for the filtering of new produced mutations.

■ Direction Control of the Parameter Vector

The differences of the parameter vectors of the last-selected mutations determine a preference direction in the parameter area. The produced mutations are shifted in the parameter area by the scaled difference vector.

■ Manually Adjustable Mutation Rate

The rate of the parameter changes can be adjusted manually; if only details are concerned, a minimum adjustment is possible.

■ Joining of Two Parameter Vectors (Marriage)

Attributes of two interesting forms can be connected by different manually adjustable techniques.

■ Fixing of Sub Structures

This can be implemented if parts of the form should no longer be modified.

■ History

Stores history of already-produced forms with optional access to each form.

Latham produced sets of animations with Todd, such as “The Conquest of Form” (1989), “A Sequence from the Evolution of Form” (1990), and “Mutations” (1991), which were shown worldwide. Finally they won the research prize of IMAGINA in Monte Carlo in 1990. In 1994 Latham founded the company ArtWorks[13], which designs new concepts for games on this basis[14].