|

|

|

|

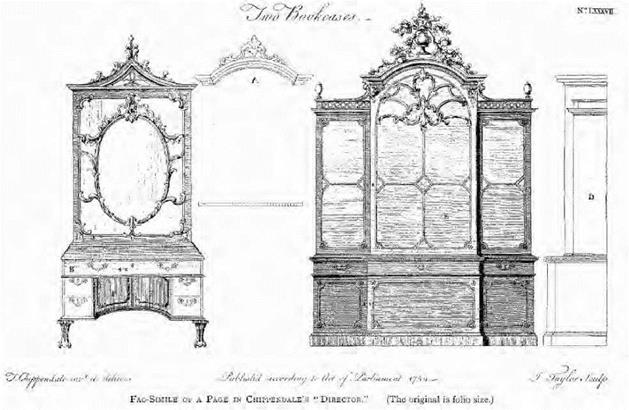

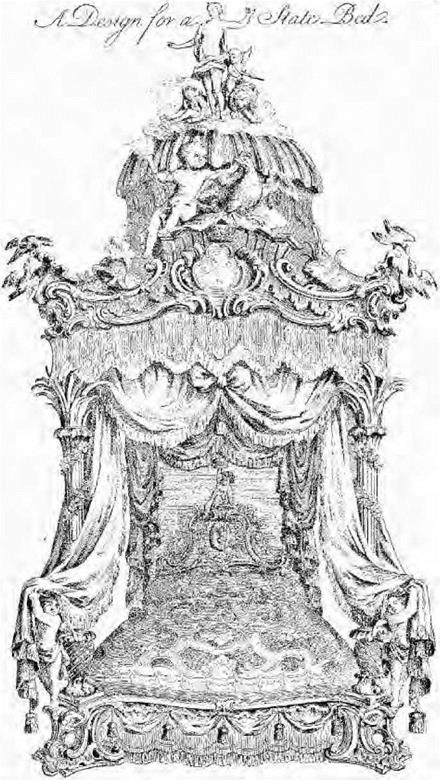

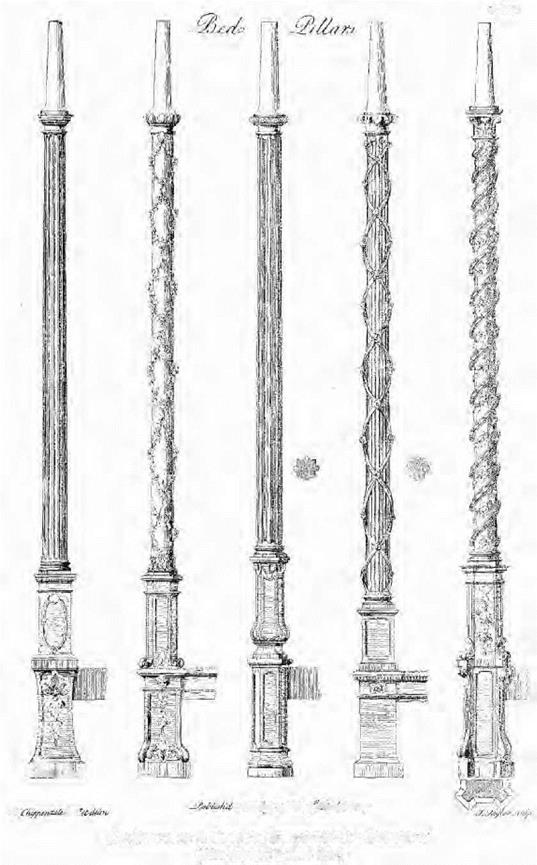

In the chapter on Louis XV. and Louis XVI. furniture, it has been shewn how France went through a similar change about this same period. In Chippendale’s chairs and console tables, in his state bedsteads and his lamp-stands, one can recognise the broken scrolls and curved lines, so familiar in the bronze mountings of Caffieri. The influence of the change which had occurred in France during the Louis Seize period is equally evident in the Adams’ treatment. It was helped forward by the migration into this country of skilled workmen from France, during the troubles of the revolution at the end of the century. Some of Chippendale’s designs bear such titles as "French chairs" or a "Bombe-fronted Commode." These

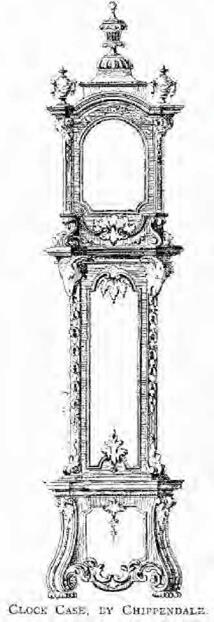

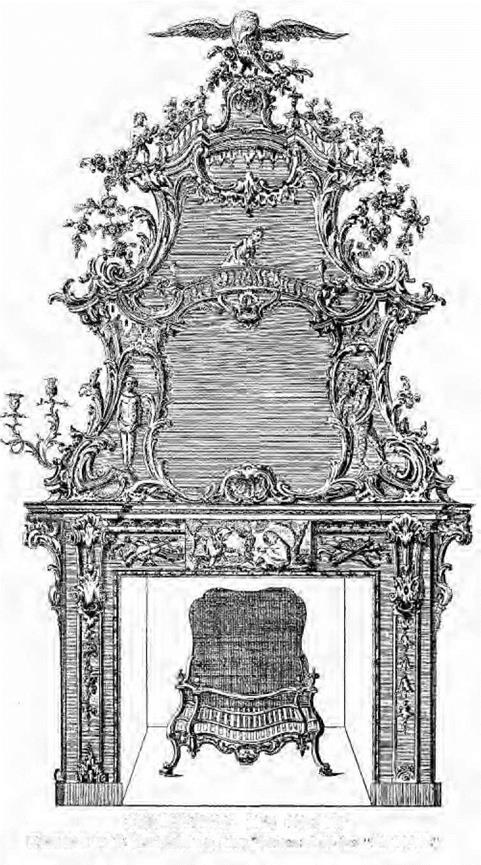

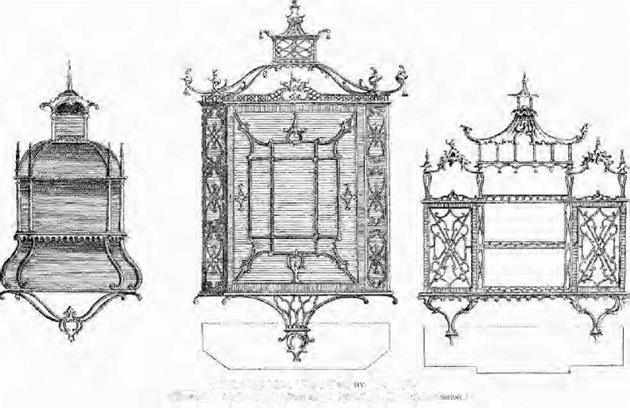

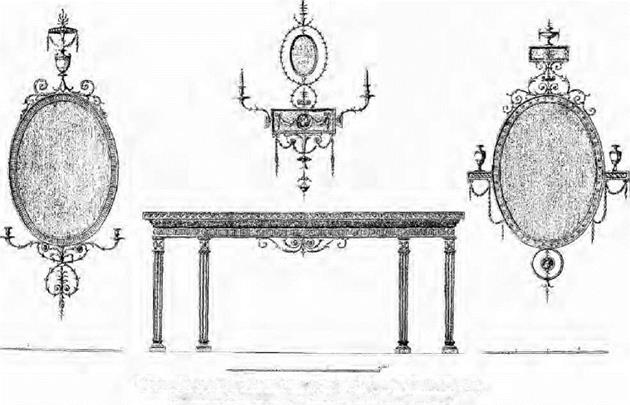

might have appeared as illustrations in a contemporary book on French furniture, so identical are they in every detail with the carved woodwork of Picau, of Cauner, or of Nilson, who designed the flamboyant frames of the time of Louis XV. Others have more individuality. In his mirror frames he introduced a peculiar bird with a long snipe-like beak, and rather impossible wings, an imitation of rockwork and dripping water, Chinese figures with pagodas and umbrellas; and sometimes the illustration of Aesop’s fables interspersed with scrolls and flowers. By dividing the glass unequally, by the introduction into his design of bevelled pillars with carved capitals and bases, he produced a quaint and pleasing effect, very suitable to the rather effeminate fashion of his time, and in harmony with three-cornered hats, wigs and patches, embroidered waistcoats, knee breeches, silk stockings, and enamelled snuff-boxes. In some of the designs there is a fanciful Gothic, to which he makes special allusion in his preface, as likely to be considered by his critics as impracticable, but which he undertakes to produce, if desired—

"Though some of the profession have been diligent enough to represent them (espescially those after the Gothick and Chinese manner) as so many specious drawings impossible to be worked off by any mechanick whatsoever. I will not scruple to attribute this to Malice, Ignorance, and Inability; and I am confident I can convince all Noblemen, Gentlemen, or others who will honour me with their Commands, that every design in the book can be improved, both as to Beauty and Enrichment, in the execution of it, by

"Their most obedient servant,

"THOMAS CHIPPENDALE."

The reader will notice that in the examples selected from Chippendale’s book there are none of those fretwork tables and cabinets which are generally termed "Chippendale." We know, however, that besides the designs which have just been described, and which were intended for gilding, he also made mahogany furniture, and in the "Director" there are drawings of chairs, washstands, writing-tables and cabinets of this description. Fretwork is very rarely seen, but the carved ornament is generally a foliated or curled endive scroll; sometimes the top of a cabinet is finished in the form of a Chinese pagoda. Upon examining a piece of furniture that may reasonably be ascribed to him, it will be found of excellent workmanship, and the wood, always mahogany without any inlay, is richly marked, shewing a careful selection of material.

|

|

|

Fm>Simjls of a Page tv Сн»і*рершд±,е,5 “ Director ■’

(The original is folio size.)

![]()

A£Ctt?-*Jt>Sg A-‘ /Jt’/i cj-y7siruu>ff/^^

A£Ctt?-*Jt>Sg A-‘ /Jt’/i cj-y7siruu>ff/^^

Fac-Simile оу a Page in Сяіргеляаї-e’s M Diioictoj<, ‘

(The original is folio size )

CHlMNfeYpfECfc AMD MlFrROR.

![]()

iftSl&KJin ЫУ ї СНІІ’ГКЯРЛІ. Е: ЛУП. t’L’liLU’l-l ІГЛЗ Itf nj.-,

iftSl&KJin ЫУ ї СНІІ’ГКЯРЛІ. Е: ЛУП. t’L’liLU’l-l ІГЛЗ Itf nj.-,

|

|

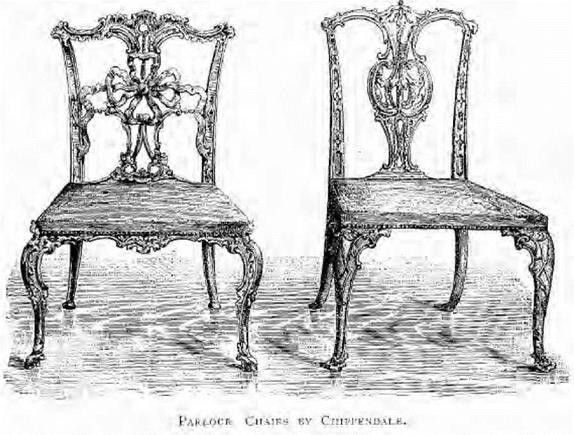

The chairs of Chippendale and his school are very characteristic. If the outline of the back of some of them be compared with the stuffed back of the chair from Hardwick Hall (illustrated in Chap. IV.) it will be seen that the same lines occur, but instead of the frame of the back being covered with silk, tapestry, or other material—as in William III.’s time—Chippendale’s are cut open into fanciful patterns; and in his more highly ornate work, the twisted ribands of his design are scarcely to be reconciled with the use for which a dining room chair is intended. The well-moulded sweep of his lines, however, counterbalances this defect to some extent, and a good Chippendale mahogany chair will ever be an elegant and graceful article of furniture.

One of the most graceful chairs of about the middle of the century, in the style of Chippendale’s best productions, is the Master’s Chair in the Hall of the Barbers’ Company. Carved in rich Spanish mahogany, and upholstered in morocco leather, the ornament consists of scrolls and cornucopia, with flowers charmingly disposed, the arms and motto of the Company being introduced. Unfortunately, there is no certain record as to the designer and maker of this beautiful chair, and it is to be regretted that the date (1865), the year when the Hall was redecorated, should have been placed in prominent gold letters on this interesting relic of a past century.

|

|

Apart from the several books of design noticed in this chapter, there were published two editions of a work, undated, containing many of the drawings found in Chippendale’s book. This book was entitled, "Upwards of One Hundred New and Genteel Designs, being all the most approved patterns of household furniture in the French taste. By a Society of Upholders and Cabinet makers." It is probable that Chippendale was a member of this Society, and that some of the designs were his, but that he severed himself from it and published his own book, preferring to advance his individual reputation. The "sideboard" which one so generally hears called "Chippendale" scarcely existed in his time. If it did, it must have been quite at the end of his career. There were side tables, sometimes called "Side-Boards," but they contained neither cellaret nor cupboard: only a drawer for table linen.

The names of two designers and makers of mahogany ornamental furniture, which deserve to be remembered equally with Chippendale, are those of W. Ince and J. Mayhew, who were partners in business in Broad Street, Golden Square, and contemporary with him. They also published a book of designs which is alluded to by Thomas Sheraton in the preface to his "Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book," published in 1793. A few examples from Ince and Mayhew’s "Cabinet Maker’s Real Friend and Companion" are given, from which it is evident that, without any distinguishing brand, or without the identification of the furniture with the designs, it is difficult to distinguish between the work of these contemporary makers.

It is, however, noticeable after careful comparison of the work of Chippendale with that of Ince and Mayhew, that the furniture designed and made by the latter has many more of the characteristic details and ornaments which are generally looked upon as denoting the work of Chippendale; for instance, the fretwork ornaments finished by the carver, and then applied to the plain mahogany, the open-work scroll-shaped backs to encoignures or china shelves, and the carved Chinaman with the pagoda. Some of the frames of chimney glasses and pictures made by Ince and Mayhew are almost identical with those of Chippendale.

Other well known designers and manufacturers of this time were Hepplewhite, who published a book of designs very similar to those of his contemporaries, and Matthias Lock, some of whose original drawings were on view in the Exhibition of 1862, and had interesting memoranda attached, giving the names of his workmen and the wages paid: from these it appears that five shillings a day was at that time sufficient remuneration for a skilful wood carver.

Another good designer and maker of much excellent furniture of this time was "Shearer," who has been unnoticed by nearly all writers on the subject. In an old book of designs in the author’s possession, "Shearer delin" and "published according to Act of Parliament, 1788," appears underneath the representations of sideboards, tables, bookcases, dressing tables, which are very similar in every way to those of Sheraton, his contemporary.

A copy of Hepplewhite’s book, in the author’s possession (published in 1789), contains 300 designs "of every article of household furniture in the newest and most approved taste," and it is worth while to quote from his preface to illustrate the high esteem in which English cabinet work was held at this time.

"English taste and workmanship have of late years been much sought for by surrounding nations; and the mutability of all things, but more especially of fashions, has rendered the labours of our predecessors in this line of little use; nay, in this day can only tend to mislead those foreigners who seek a knowledge of English taste in the various articles of household furniture."

|

It is amusing to think how soon the "mutabilities of fashion" did for a time supersede many of his designs.

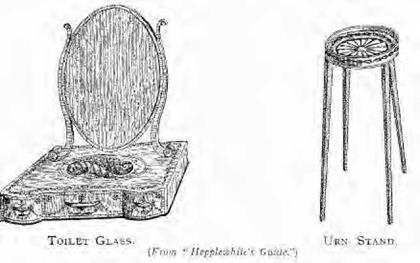

A selection of designs from his book is given, and it will be useful to compare them with those of other contemporary makers. From such a comparison it will be seen that in the progress from the rococo of Chippendale to the more severe lines of Sheraton, Hepplewhite forms a connecting link between the two.

|

|

The names given to some of these designs appear curious; for instance:

"Rudd’s table or reflecting dressing table," so called from the first one having been invented for a popular character of that time.

"Knife cases," for the reception of the knives which were kept in them, and used to "garnish" the sideboards.

"Cabriole chair," implying a stuffed back, and not having reference, as it does now, to the curved form of the leg.

"Bar backed sofa," being what we should now term a three or four chair settee, i. e., like so many chairs joined and having an arm at either end.

"Library case" instead of Bookcase.

"Confidante" and "Duchesse," which were sofas of the time.

"Gouty stool," a stool having an adjustable top.

"Tea chest," "Urn stand," and other names which have now disappeared from ordinary use in describing similar articles.

|

LA1>’i KV LAikJfa, ]J>LҐЧ CN 5T> GY Vf, [ N Г К. ■■ RepjOii’j’j’riL Iij Pti^t^aphr ІГІ..І1І, . .PiijiL in Llli.1 ALLrt. iM-І ]£ік!>:к:{гіпп. |

Hepplewhite had a speoialite, to which he alludes in his book, and of which he gives several designs. This was his japanned or painted furniture: the wood was coated with a preparation after the manner of Chinese or Japanese lacquer, and then decorated, generally with gold on a black ground, the designs being in fruits and flowers: and also medallions painted in the style of Cipriani and Angelica Kauffmann. Subsequently, furniture of this character, instead of being japanned, was only painted white. It is probable that many of the chairs of this time which one sees, of wood of inferior quality, and with scarcely any ornament, were originally decorated in the manner just described, and therefore the "carving" of details would have been superfluous. Injury to the enamelling by wear and tear was most likely the cause of their being stripped of their rubbed and partly obliterated decorations, and they were then stained and polished, presenting an appearance which is scarcely just to the designer and manufacturer.

In some of Hepplewhite’s chairs, too, as in those of Sheraton, one may fancy one sees evidence of the squabbles of two fashionable factions of this time, "the Court party" and the "Prince’s party," the latter having the well known Prince of Wales’ plumes very prominent, and forming the ornamental support of the back of the chair. Another noticeable enrichment is the carving of wheat ears on the shield shape backs of the chairs.

"The plan of a room shewing the proper distribution of the furniture," appears on p. 193 to give an idea of the fashion of the day; it is evident from the large looking glass which overhangs the sideboard that the fashion had now set in to use these mirrors. Some thirty or forty year later this mirror became part of the sideboard, and in some large and pretentious designs which we have seen, the sideboard itself was little better than a support for a huge glass in a heavily carved frame.

The dining tables of this period deserve a passing notice as a step in the development of that important member of our "Lares and Penates." What was and is still called the "pillar and claw" table, came into fashion towards the end of last century. It consisted of a round or square top supported by an upright cylinder, which rested on a plinth having three, or sometimes four, feet carved as claws. In order to extend these tables for a larger number of guests, an arrangement was made for placing several together. When apart, they served as pier or side tables, and some of these—the two end ones, being semi-circular—may still be found in some of our old inns.17

It was not until 1800 that Richard Gillow, of the well-known firm in Oxford Street, invented and patented the convenient telescopic contrivance which, with slight improvements, has given us the table of the present day. The term still used by auctioneers in describing a modern extending table as "a set of dining tables," is, probably, a survival of the older method of providing for a dinner party. Gillow’s patent is described as "an improvement in the method of constructing dining and

other tables calculated to reduce the number of legs, pillars and claws, and to facilitate and render easy, their enlargement and reduction."

G і KANDOLL.

Parlour Chair,

WITH Рк і MCE OK Walks’ Plumcs

Pier Tajle

DESIGNS OF FURNITURE.

From Hi^i’i’LLWHiTES ”Guide," PUiJLiuJibD J7S7

As an interesting link between the present and the past it may be useful here to introduce a slight notice of this well-known firm of furniture manufacturers, for which the writer is indebted to Mr. Clarke, one of the present partners of Gillows. "We have an unbroken record of books dating from 1724, but we existed long anterior to this: all records were destroyed during the Scottish Rebellion in 1745." The house originated in Lancaster, which was then the chief port in the north, Liverpool not being in existence at the time, and Gillows exported furniture largely to the West Indies, importing rum as payment, for which privilege they held a special charter. The house opened in London in 1765, and for some time the Lancaster books bore the heading and inscription, "Adventure to London." On the architect’s plans for the premises now so well-known in Oxford Street, occur these words, "This is the way to Uxbridge." Mr. Clarke’s information may be supplemented by adding that from Dr. Gillow, whom the writer had the pleasure of

meeting some years ago, and was the thirteenth child of the Richard Gillow before mentioned; he learnt that this same Richard Gillow retired in 1830, and died as late as 1866 at the age of 90. Dowbiggin, founder of the firm of Holland and Sons, was an apprentice to Richard Gillow.

Mahogany may be said to have come into general use subsequent to 1720, and its introduction is asserted to have been due to the tenacity of purpose of a Dr. Gibbon, whose wife wanted a candle box, an article of common domestic use of the time. The Doctor, who had laid by in the garden of his house in King Street, Covent Garden, some planks sent to him by his brother, a West Indian captain, asked the joiner to use a part of the wood for this purpose; it was found too tough and hard for the tools of the period, but the Doctor was not to be thwarted, and insisted on harder-tempered tools being found, and the task completed; the result was the production of a candle box which was admired by every one. He then ordered a bureau of the same material, and when it was finished invited his friends to see the new work; amongst others, the Duchess of Buckingham begged a small piece of the precious wood, and it soon became the fashion. On account of its toughness, and peculiarity of grain, it was capable of treatment impossible with oak, and the high polish it took by oil and rubbing (not French polish, a later invention), caused it to come into great request. The term "putting one’s knees under a friend’s mahogany," probably dates from about this time.

Thomas Sheraton, who commenced work some 20 years later than Chippendale, and continued it until the early part of the nineteenth century, accomplished much excellent work in English furniture.

|

КкЕЕГІОІ. Ї. ТА-Ш. Е. EV SlI&fijlTf’V |

The fashion had now changed; instead of the rococo or rock work (literally rock- scroll) and shell (rooquaille et oooquaille) ornament, which had gone out, a simpler and more severe taste had come in. In Sheraton’s cabinets, chairs, writing tables, and occasional pieces we have therefore no longer the cabriole leg or the carved ornament; but, as in the case of the brothers Adam, and the furniture designed by them for such houses as those in Portland Place, we have now square tapering legs, severe lines, and quiet ornament. Sheraton trusted almost entirely for decoration to his marqueterie. Some of this is very delicate and of excellent workmanship. He introduced occasionally animals with foliated extremities into his scrolls, and he also inlaid marqueterie trophies of musical instruments; but as a rule the decoration was in wreaths of flowers, husks, or drapery, in strict adherence to the fashion of the decorations to which allusion has been made. A characteristic feature of his cabinets was the swan-necked pediment surmounting the cornice, being a revival of an ornament fashionable during Queen Anne’s reign. It was then chiefly found in stone, marble, or cut brickwork, but subsequently became prevalent in inlaid woodwork.

Sheraton was apparently a man very well educated for his time, whether self taught or not one cannot say; but that he was an excellent draughtsman, and had a complete knowledge of geometry, is evident from the wonderful drawings in his book, and the careful though rather verbose directions he gives for perspective drawing. Many of his numerous designs for furniture and ornamental items, are drawn to a scale with the geometrical nicety of an engineer’s or architect’s plan: he has drawn in elevation, plan, and minute detail, each of the five architectural orders.

The selection made here from his designs for the purposes of illustration, is not taken from his later work, which properly belongs to a future chapter, when we come to consider the influence of the French Revolution, and the translation of the "Empire" style to England. Sheraton published "The Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing Book" in 1793, and the list of subscribers whose names and addresses are given, throws much light on the subject of the furniture of his time.18 Amongst these are many of his aristocratic patrons and no less than 450 names and addresses of cabinet makers, chair makers and carvers, exclusive of harpsichord manufacturers, musical instrument makers, upholsterers, and other kindred trades. Included with these we find the names of firms who, from the appointments they held, it may be inferred, had a high reputation for good work and a leading position in the trade, but who, perhaps from the absence of a taste for ‘ ‘getting into print" and from the lack of any brand or mark by which their work can be identified, have passed into oblivion while their contemporaries are still famous. The following names taken from this list are probably those of men who had for many years conducted well known and old established businesses, but would now be but poor ones to "conjure" with, while those of Chippendale, Sheraton, or Hepplewhite, are a ready passport for a doubtful specimen. For instance:—France, Cabinet Maker to His Majesty, St. Martin’s Lane; Charles Elliott, Upholder to His Majesty and Cabinet Maker to the Duke of York, Bond Street; Campbell and Sons, Cabinet Makers to the Prince of Wales, Mary-le-bone

Street, London. Besides those who held Royal appointments, there were other manufacturers of decorative furniture—Thomas Johnson, Copeland, Robert Davy, a French carver named Nicholas Collet, who settled in England, and many others.

In Mr. J. H. Pollen’s larger work on furniture and woodwork, which includes a catalogue of the different examples in the South Kensington Museum, there is a list of the various artists and craftsmen who have been identified with the production of artistic furniture either as designers or manufacturers, and the writer has found this of considerable service. In the Appendix to this work, this list has been reproduced, with the addition of several names (particularly those of the French school) omitted by Mr. Pollen, and it will, it is hoped, prove a useful reference to the reader.

Although this chapter is somewhat long, on account of the endeavour to give more detailed information about English furniture of the latter half of last century, than of some other periods, in consequence of the prevailing taste for our National manufacture of this time, still, in concluding it, a few remarks about the "Sideboard" may be allowed.

The changes in form and fashion of this important article of domestic furniture are interesting, and to explain them a slight retrospect is necessary. The word "Buffet," sometimes translated "Sideboard," which was used to describe continental pieces of furniture of the 15th and 16th centuries, does not designate our Sideboard, which may be said to have been introduced by William III.; and of which kind there is a fair specimen in the South Kensington Museum; an illustration of it has been given in the chapter dealing with that period.

The term "stately sideboard" occurs in Milton’s "Paradise Regained," which was published in 1671, and Dryden, in his translation of Juvenal, published in 1693, when contrasting the furniture of the classical period of which he was writing with that of his own time, uses the following line:—

"No sideboards then with gilded plate were dressed."

The fashion in those days of having symmetrical doors in a room, that is, false doors to correspond with the door used for exit, which one still finds in many old houses in the neighbourhood of Portland Place, and particularly in the palaces of St. James’ and of Kensington, enabled our ancestors to have good cupboards for the storage of glass, crockery, and reserve wine. After the middle of the eighteenth century, however, these extra doors and the enclosed cupboard gradually disappeared, and soon after the mahogany side table came into fashion it became the custom to supplement this article of furniture by a pedestal cupboard on either

side (instead of the cupboards alluded to), one for hot plates and the other for wine. Then, as the thin legs gave the table rather a lanky appearance, the garde de vin, or cellaret, was added in the form of an oval tub of mahogany with bands of brass, sometimes raised on low feet with castors for convenience, which was used as a wine cooler. A pair of urn-shaped mahogany vases stood on the pedestals, and these contained—the one hot water for the servants’ use in washing the knives, forks and spoons, which being then much more valuable were limited in quantity, and the other held iced water for the guests’ use.

A brass rail at the back of the side table with ornamental pillars and branches for candles was used, partly to enrich the furniture, and partly to form a support to the handsome pair of knife and spoon cases, which completed the garniture of a gentleman’s sideboard of this period.

The full page illustrations will give the reader a good idea of this arrangement, and it would seem that the modern sideboard is the combination of these separate articles into one piece of furniture—at different times and in different fashions— first the pedestals joined to the table produced our "pedestal sideboard," then the mirror was joined to the back, the cellarette made part of the interior fittings, and the banishment of knife cases and urns to the realms of the curiosity hunter, or for conversion into spirit cases and stationery holders. The sarcophagus, often richly carved, of course succeeded the simpler cellaret of Sheraton’s period.

Before we dismiss the furniture of the "dining room" of this period, it may interest some of our readers to know that until the first edition of "Johnson’s Dictionary" was published in 1755, the term was not to be found in the vocabularies of our language designating its present use. In Barrat’s "Alvearic," published in 1580, "parloir," or "parler," was described as "a place to sup in." Later, "Minsheu’s Guide unto Tongues," in 1617, gave it as "an inner room to dine or to suppe in," but Johnson’s definition is "a room in houses on the first floor, elegantly furnished for reception or entertainment."

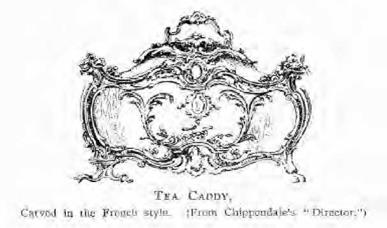

To the latter part of the eighteenth century—the English furniture of which time has been discussed in this Chapter—belong the quaint little "urn stands" which were made to hold the urn with boiling water, while the tea pot was placed on the little slide which is drawn out from underneath the table top. In those days tea was an expensive luxury, and the urn stand, of which there is an illustration, inlaid in the fashion of the time, is a dainty relic of the past, together with the old mahogany or marqueterie tea caddy, which was sometimes the object of considerable skill and care. One of these designed by Chippendale is illustrated on p. 179, and another by Hepplewhite will be found on p. 194. They were fitted with two and sometimes three bottles or tea-pays of silver or Battersea enamel, to

hold the black and green teas, and when really good examples of these daintily- fitted tea caddies are offered for sale, they bring large sums.

|

A SIDEBOARD IN MAHOGANY WITH INLAY OF SATINWOOD. In mi – vtVbt or Rudlki Aoam. |

The "wine table" of this time deserves a word. These are now somewhat rare, and are only to be found in a few old houses, and in some of the Colleges at Oxford and Cambridge. These were found with revolving tops, which had circles turned out to a slight depth for each glass to stand in, and they were sometimes shaped like the half of a flat ring. These latter were for placing in front of the fire, when the outer side of the table formed a convivial circle, round which the sitters gathered after they had left the dinner table.

One of these old tables is still to be seen in the Hall of Gray’s Inn, and the writer was told that its fellow was broken and had been "sent away." They are nearly always of good rich mahogany, and have legs more or less ornamental according to circumstances.

A distinguishing feature of English furniture of the last century was the partiality for secret drawers and contrivances for hiding away papers or valued articles; and in old secretaires and writing tables we find a great many ingenious designs which remind us of the days when there were but few banks, and people kept money and deeds in their own custody.

|

ij hr.’VT-:n (.’ll.’L-fllNU ‘..’-j |