Roland Gustavsson

Introduction—discoveries and rediscoveries for an innovative design

We are rooted in an age that seeks instant landscape effects but, from an environmental viewpoint, instant effects are not really what are wanted. Instead, a far more sustainable approach is required that involves greater richness and complexity evolving over time, directed in a knowledgeable way. Healthy cities need effective green-space networks and woodlands; not just to promote healthy living for city dwellers, but also to sustain wider biodiversity, to promote water and air quality, and to regulate climatic extremes. All this is well known, but is rarely reflected in landscape design. Rather than trying to freeze parks or gardens and making them static entities, they would be greatly enhanced if their long-time dynamic and structural changes are treated from a deep and active understanding. Moreover, rather than claiming that landscape architecture needs simplicity to be successful, it would be of great interest for the future to promote design concepts in which complexity plays a role. Considering the importance of both the outdrawn time-perspective and complexity in design, it is surprising how few books and articles are written focusing on planting design and vegetation in a city or urban rural fringe context, bridging the gap between architecture and an ecological-technical understanding.

In temperate climates, woodland is the natural state for the long-term development of landscape

|

|

7.1

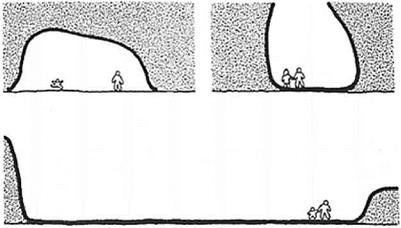

There are many possibilities for discovering the qualities of interior woodland rooms, whether they have a closed canopy or are open to the sky (upper diagrams) as opposed to the most commonly used ‘open room’ style (lower diagram) where woodland is seen purely as a structural element to define outdoor spaces

vegetation. However, the view of woodland discussed in this chapter is very different to the way it is generally conceived by designers and managers. Indeed, one of the main aims of this chapter is to rediscover the traditional meaning of woodland or forest as a rich diversity of land uses; some open, some half-open, others closed, but all within a wooded framework (Rackham 1986). A further aim is to place greater emphasis on the interior of woodlands as rich environments that appeal to all the senses, rather than viewing woodland plantations as simple structural elements in landscapes that define exterior spaces. The interior woodland should mean a choice between a whole series of interesting options, of types which all should be able to become very distinct and supplementary to each other, giving harmony or drama by contrast (Figure 7.1). Sadly, this has often been forgotten in day-to-day design. Furthermore, the chapter presents an alternative to conventional landscape design and planning, and is based on a view of woodland, forest, scrub and small-scale mosaics with open glades and meadows as a dynamic and ecologically functioning cultural concept, whether or not one is not restricted to the choice of native species.

The approach taken in this chapter is to identify a whole set of specific structural – dynamic components of woodland landscape types and to describe them in a way that makes them concrete as visions or ideal types. These types include high forest, low forest, woodland edge, half-open land, small-scale mosaics and shrub-dominated vegetation. Such types can be combined and integrated to result in a rich landscape that can cater for a wide range of uses and functions. But first we will consider in much more detail what woodland actually means, along with general design principles, before looking at the more technical aspects of the different structural types.