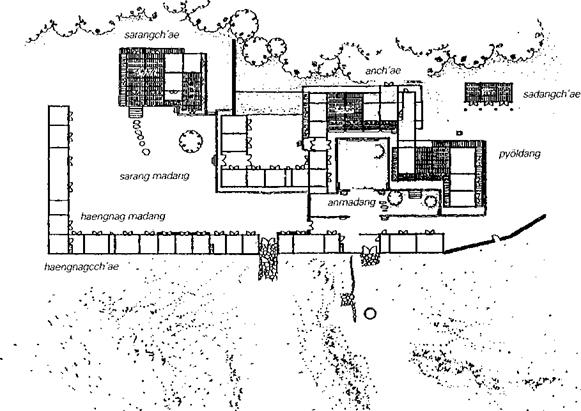

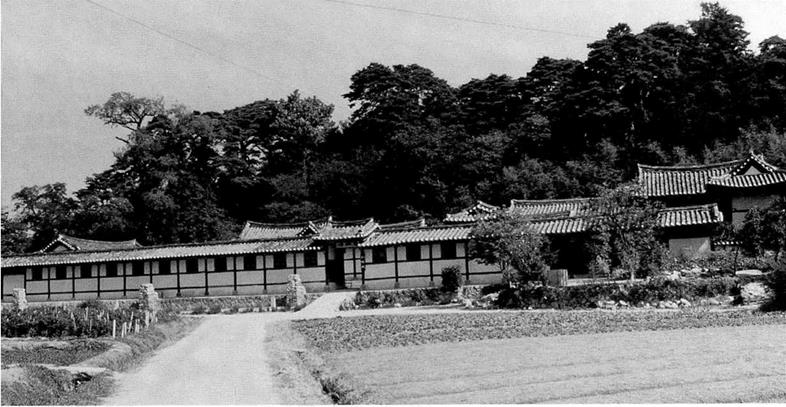

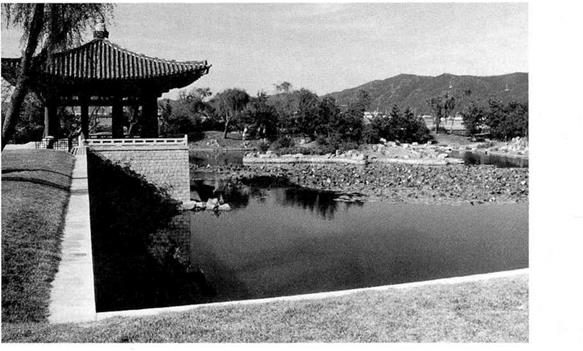

Son’gyojang in Kangnting City, Kangwon Province, is a typical example of the yangban homes built in the provinces toward the end of the Choson period (in this case, a. d. 1816). In floor plan composition, it contains all the elements symbolic of the Korean upper classes at the time. Its outer garden, consisting of a lotus pond and a pavilion, lies outside the main gate on flat ground to the southwest of the outer wall of the residential compound, which is formed by the haengnagch’ae (Figures 115.1-115.3).

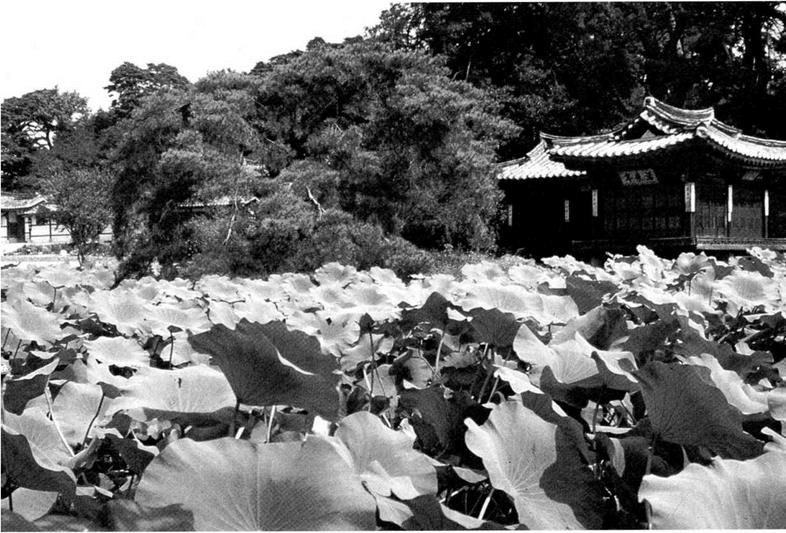

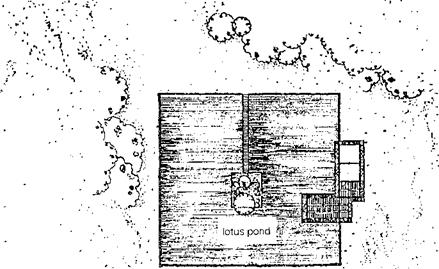

The lotus pond in Son’gyojang’s outer garden is square in shape and its walls are lined with quarried stone. The pavilion, called Hwallaejong, consists of an owiofheated wing and a wooden-floored wing, which cantilevers out over the pond. Directly in front of the pavilion, a circular island, also with quarried stone embankments, is set exactly in the center of the pond, and features a few pine trees. This is a classical Korean outer garden.

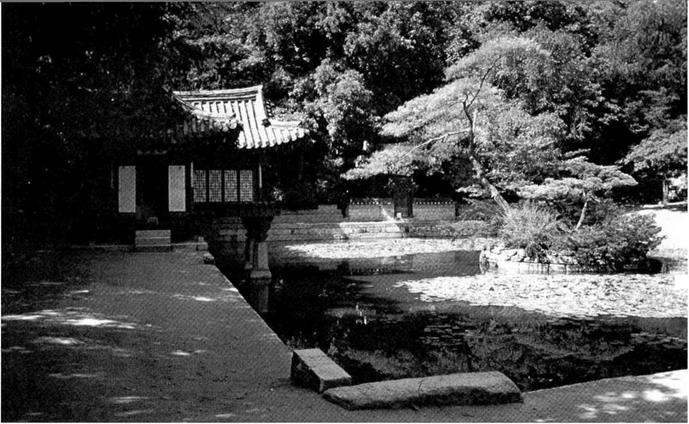

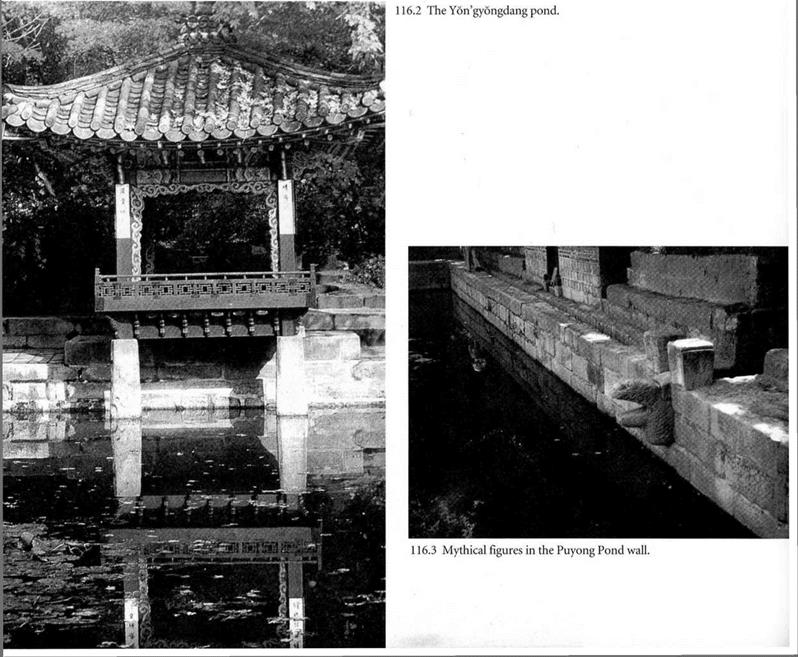

The outer garden—usually an area of flat land near the main gate and outside the wall of the residential compound—is generally laid out in straight lines and geometric forms, with particular attention paid to symmetrical balance. Islands set in decorative ponds are most often round, and are usually planted with a few pine trees. In principle, there should be no bridge connecting the island to the shore. In many cases, the corner stones and the water outlet of the pond’s quarried-stone wall are carved into the shapes of mythical animals or monsters. Thus, the overall effect contrasts sharply with the natural simplicity of the gardens inside the residential compound (Figures 116.1-116.3).

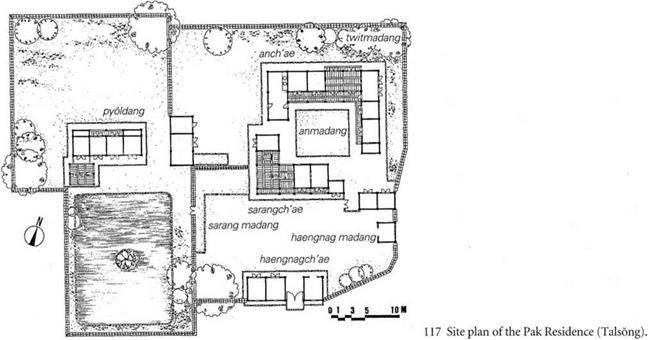

Sometimes an outer garden was laid out around a pyoldang, or an annex where the master of the household could spend time reading in private, but more often its purpose was to catch the eye of visitors passing through the main gate to the sarangch’ae. Rather than serving any particular functional purpose, its main role was as a formal symbol of the yangban household (Figure 117).

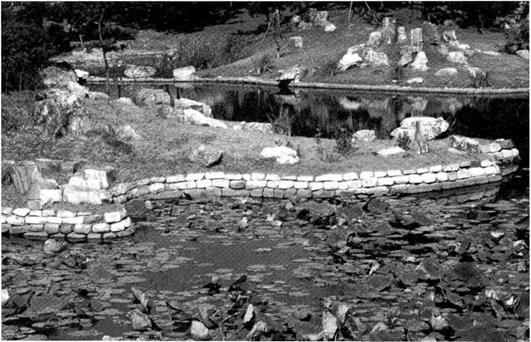

The design elements of the lotus pond and the island are rooted in the prayers for long life and perennial youth of ancient hermit wizardry. These gardens are believed to have been first built in the sixth-century Paekche palaces and can be seen in the pond of Anapchi (a. d. 671) in Kyongju, among remains discovered from the Silla Kingdom. If we look at this pond, which is still undergoing restoration, we can see that its embankments at the eastern end, closest to the original palace building, are perpendicular lines, while the western end is composed of more free-form curves. The entire pond, however, is lined with quarried stone, behind which groupings of sokkasan stones are displayed on the slope (Figures 118.1-118.2). The treatment of the pond’s edge is stylistically completely different from that of a Japanese garden—designed to express a seascape—where the ground would slope gently down into the pond and stone groupings would extend into the water.

The composition of the pond’s edge in a Japanese garden is designed to create a sense of unity between the pond and surrounding garden, but in Korea straight lines and quarried stone are used to create a sense of separateness between the viewer and the surface of the pond. This sense of separateness is heightened by the construction of a pavilion or belvedere cantilevered over the water. In Choson-period gardens all sides of these ponds are straight lines, the regularity and formalization of which differs markedly with the freedom demonstrated in the smooth curves at one end of the much older Anapchi.

As mentioned above, Kyongbokkung in Seoul was not only a royal palace but also the seat of government and a place for important ceremonies and the granting of audiences. Northwest of the main administrative apartments

|

|

|

twitmadang |

|

115.1 Site plan of a yangban estate with an outer garden (Son’gyojang, Kangnung). |

|

115.2 The Son’gyojang exterior facade. |

|

115.3 Hwallaejong pavilion and lotus pond. |

|

116.1 Puyong Pond (Piwon). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

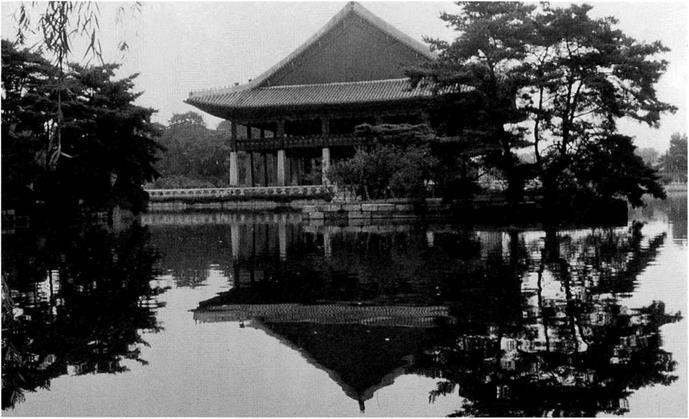

is the enormous Kyonghoeru standing on a plaza of stone pilotis, which was used as a place for greeting and entertaining visitors. The pond alongside this building is a rectangular expanse of water 113 meters (370 feet) from north to south and 128 meters (420 feet) from east to west. It features two long, narrow islands planted with pine trees. The sides of the pond are perfectly straight and lined with quarried stone. The Kyonghoeru pond is one of the best extant examples of Choson-period design, but its form owes much to the traditions passed down from the creators of Anapchi (Figure 119).

The outer gardens of yangban estates also share with the royal palaces the same traditional forms handed down from the days of the Unified Silla and Koryo kingdoms. In the royal palaces, the outer gardens are characterized by straight lines and geometric patterns while the private rear gardens retain a high degree of naturalism. The same contrast between a highly ordered and a natural approach is seen in the outer gardens and rear gardens of yangban estates. Following the forms inherited from royal palace gardens, the yangban outer gardens—so unique among all the gardens of traditional Korean residences—acquired the same authoritative and symbolic qualities.

Interestingly, a form similar to these outer garden rec

tangular ponds and embankments of quarried stone appears as a garden-making method during the early Edo period in Japan. It can be seen in the section of the Nijojo pond known as Ikejirifunadamari, the pond in front of the moon-viewing platform, and the Shoiken funatsukiba (boat mooring inlet) at Katsura Rikyu, all of which are attributed to designer Kobori Enshu. Many such linear compositions, which disappeared from Japan, also appear in the drawings entitled Kan’eido sentd nyoin gosho sashizu. This has given rise to a great deal of speculation about whether it might be a direct sign of an exchange of gardening techniques between Korea and Japan.