Shinden-zukuri buildings were single-room residences in which living space was defined with furnishings. There were no distinct rooms, and the relationship between people and furniture was fluid.

The architectural interior and exterior were partitioned by shitomido latticed shutters and tsumado paneled doors, both of which swing on hinges. In their open position, these fixtures leave the entire one-bay space between columns unobstructed, and so unite interior and exterior. For this reason the interior and exterior developed in tandem.

Shinden-zukuri living took place in spaces defined simply by movable furnishings, without the designation of specific rooms for specific purposes. By extension, it is safe to say that neither were there fixed positions in the building from which the garden was intended to be viewed.

With shitomido in their open position, the structural composition of the shinden afforded a panoramic view that encompassed the entire south garden along with the palace interior and exterior. The world that unfolded in this space, including poetry and narrative yamato-e painting, was informed by the aesthetic of miyabi, or refined beauty, that permeated all of life at the Heian court. Like gardens, painting and poetry of this period also expressed “the natural landscape” and “famous places of scenic beauty.”

Yamato-e painting is narrative. Buildings are depicted in the fukinuki-yatai compositional technique in which roofs and ceilings are omitted to show interior and exterior scenes from a bird’s-eye, panoramic view. Famous places of scenic beauty from the four corners of the capital in the four seasons arc expressed on one picture plane connected by mist and clouds in the kumogasumi technique. Waka poems that extol the seasonal characteristics of these famed places are included calligraphically as part of the painting. With kasaneirome, bands of contrasting colors formed by layers of robes worn by Heian empresses and court ladies, providing yet another wash of color, the shinden-zukuri moya core building, hisashi outer aisles, sukird open corridors, and garden formed a tangible setting for the world of miyabi.

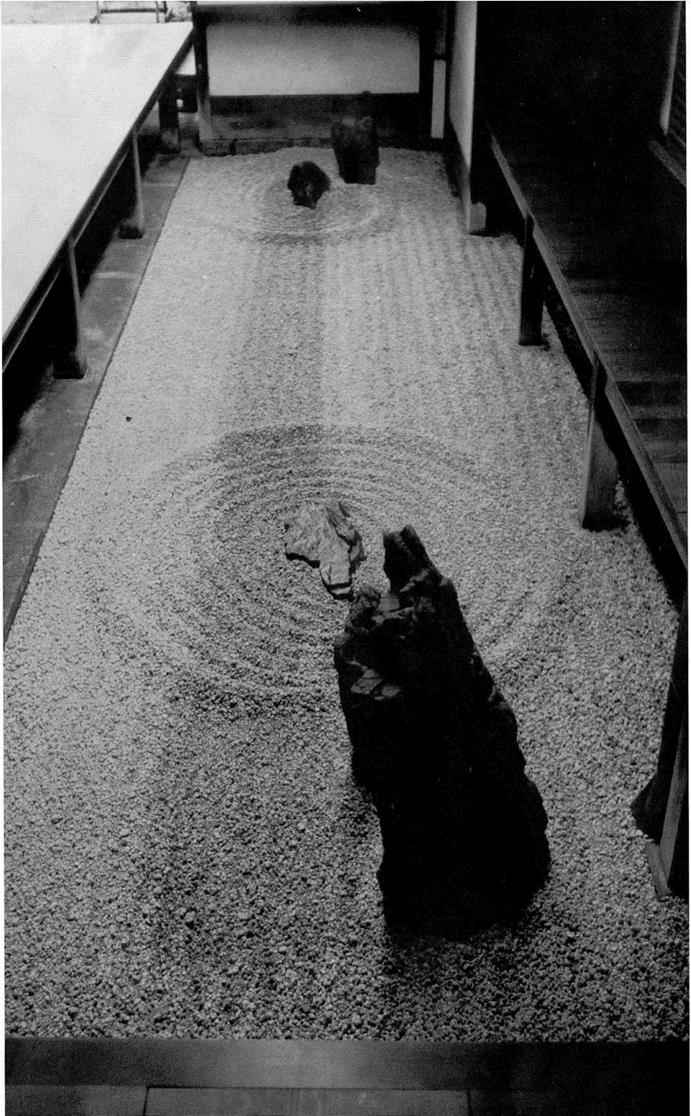

As the distance between the shinden and tainoya opposing annexes on the east-west axis was also condensed, haji – tomi half shutters, misu bamboo blinds, zesho thin summer curtains, and kabeshiro heavy drapes were hung, and kicho free-standing textile screens placed, to interrupt sight lines. The design approach used for the corresponding tsuboniwa courtyard gardens—composed of plants, hillside fields, the garden stream and springs—located between these two buildings shifted from the broad panoramic view used in the south garden to an intimate one-to-one relationship between garden and viewer (see Figure 10.4). This more intimate relationship was to become the mainstream in Muromachi-period garden design (Figures 14.1-14.2).

The aesthetic of miyabi arose specifically in the context of the Heian court and fell from favor together with it, whereas the philosophical basis of another aesthetic ideal cultivated during the Heian period, mono no aware, retained its appeal and became the basis for the more somber aesthetics of medieval |apan. Mono no aware— the capacity to be emotionally moved by “things”—conveys a heightened sensitivity to the ephemeral beauty embodied in nature and human life, and thus contains a hint of sadness.

|

;F3lv> • |

|

|

В – ‘ 1 |

14.1 Tsuboniwa bordered by the shinden, tainoya, and sukird, Nin’naji, Kyoto.

With the close of the Heian period, the shinden—where building interior and exterior were one—was divided into fixed rooms. With the further limitations that arose from the subdivision of the one – cho block into one-fourth – and one-eighth-cho sites, the relationship between architecture and garden changed radically. An entry appearing in the late-Heian Nihon kiryaku (Outline record of Japan) regarding residential zoning restrictions, listed under the year a. D. 1030, states that: “the residences of regional lords

shall not exceed one-fourth-c/20.” This was just two years after the birth of Sakuteiki author Tachibana no Toshitsuna.

In many respects, Sakuteiki reflects the values of the transitional period from the gradual decline of the Heian court life at its zenith to the more austere Japanese middle ages (late Heian, Kamakura and Muromachi periods), and the sweeping structural and aesthetic changes that would be seen in the architecture and gardens to come.

14.2 Tsuboniwa, Daitokuji Ryogen’in, Kyoto. ►

|

|