Benjamin Bucktrout is of extreme importance to the study of Y’irginia furniture, due largely to his stamped signature on the back of an important Masonic Master’s chair (fig. 49). It is currently the only known piece of signed Williamsburg work and is a cornerstone in the study of the 1 lay shop.

Benjamin Bucktrout is of extreme importance to the study of Y’irginia furniture, due largely to his stamped signature on the back of an important Masonic Master’s chair (fig. 49). It is currently the only known piece of signed Williamsburg work and is a cornerstone in the study of the 1 lay shop.

Bucktrout, who referred to himself as a cabinetmaker from London, probably served his apprenticeship in that city and may have come to Williamsburg as a journeyman or identured servant to Anthony Hay.19 An entry in the Virginia Gazette Day Book for September 28, 1765 shows that he paid five shillings toward sundry accounts for Hay, a common practice among shop employees and one that clearly links the two men during Bucktrout’s earliest period in America.

By the summer of 1766, however, Bucktrout had established an independent business of his own and had placed an advertisement to advise the public of his new location:

B. BUCKTROUT CABINET MAKER, from

LONDON, on the main street near the Capitol in Williamsburg, makes all sorts of cabinetwork, either plain or ornamental, in the neatest and newest fashions. I le hopes to give statisfaction to all Gentlemen w ho shall please to favour him with their commands.

N. B. Where likew ise may be had the mathematical GOUTY CHAIR.20

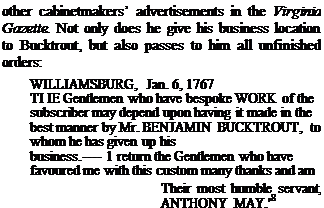

1 lis stay at the new location was short lived, however, for in 1767 Bucktrout took over I lay’s old business.

Some indication of Bucktrout’s English background can be gained through a study of the items he made and repaired at his new location. One of the most unusual forms noted in his first Virginia Gazette advertisement was a “mathematical gouty chair.” It was not the first time that this obscure form had appeared in Williamsburg. According to the Virginia Gazette daybook of September 7, 1765, 1 lay had placed a similar ad in an issue of the paper that no longer survives. When considering the character of Bucktrout’s later notices and the fact that he was working in the Hay shop during that period, it becomes apparrent that Bucktrout had introduced the unusual form to Williamsburg.

In 1767, after Bucktrout returned to the Nicholson Street shop as its new master, he advertised the manufacture and repair of spinets and harpsichords. During the Revolution he constructed a manually operated powder mill, and although it appears to have been a successful venture, he encountered

considerable difficulty in obtaining payment for his services. John Page, burgess from Gloucester County, wrote to Richard I lenry Lee in February of 1776 and complained of the situation:

I moved too, with like [little] success that the sum of £.40 should be paid to Bucktrout, for his ingenuity in constructing; and to defray the expense of erecting a powder mill; and to enable him to prosecute his plan of working up the Salt Petre which may be collected in the neighboring Counties, w ith his I land Powder Mill now at work in this City.21

Bucktrout was also engaged in the repair of umbrellas, a specialty that required great dexterity and skill with a variety of materials. I le repaired an umbrella for I lenry Morse in I77522 and continued w ith this sideline for nearly twenty years, as evidenced by a 1794 bill from Bucktrout to Joseph Prentis:

Deer 16 to putting new walcbone in umbrclla£-1-3 New wire for top takeing out fixn Curve I-323

While accounts exist for many repairs and odd jobs handled by Bucktrout or someone in his employ, the accounts mentioned above are similar in nature: they require special mechanical skills combined with fine workmanship in varied and somewhat unusual media. This combination, rare in colonial Virginia, could have been acquired in London and may reflect Bucktrout’s training there in a special branch of the cabinctmaking trade, or as a musical-instrument maker, the latter also requiring skill in varied materials. Bucktrout’s one advertisement for spinets and harpsichords supports this conclusion, although a lack of demand for such work could account for the later emphasis on cabinetmaking in his newspaper notices.

Sometime after moving to the Hay shop, Bucktrout entered into partnership with W illiam Kennedy. The venture w as of short duration, how ever, and nothing is known about Kennedy’s background. The only records concerning their business are two advertisements in the Virginia Gazette:

WILLIAMSBURG, Feb. 16, 1769 The partnership between Bucktrout and Kennedy being dissolved, the subscriber now carries on the cabinet making business, as usual, at the shop formerly kept by Mr. I lay, where he hopes for the encouragement of his old customers, and others.

BENJAMIN BUCKTROUT24

Apparently communication between the two craftsmen was lacking, since two weeks after Bucktrout had declared the business “dissolved” Kennedy advised the public that it was not yet so:

WILLIAMSBURG, March I, 1769

Tl IK partnership between Bucktrout and Kennedy, though not yet dissolved, will terminate as soon as the work w hich is already bespoken can be finished, and matters brought to a proper settlement; at which time