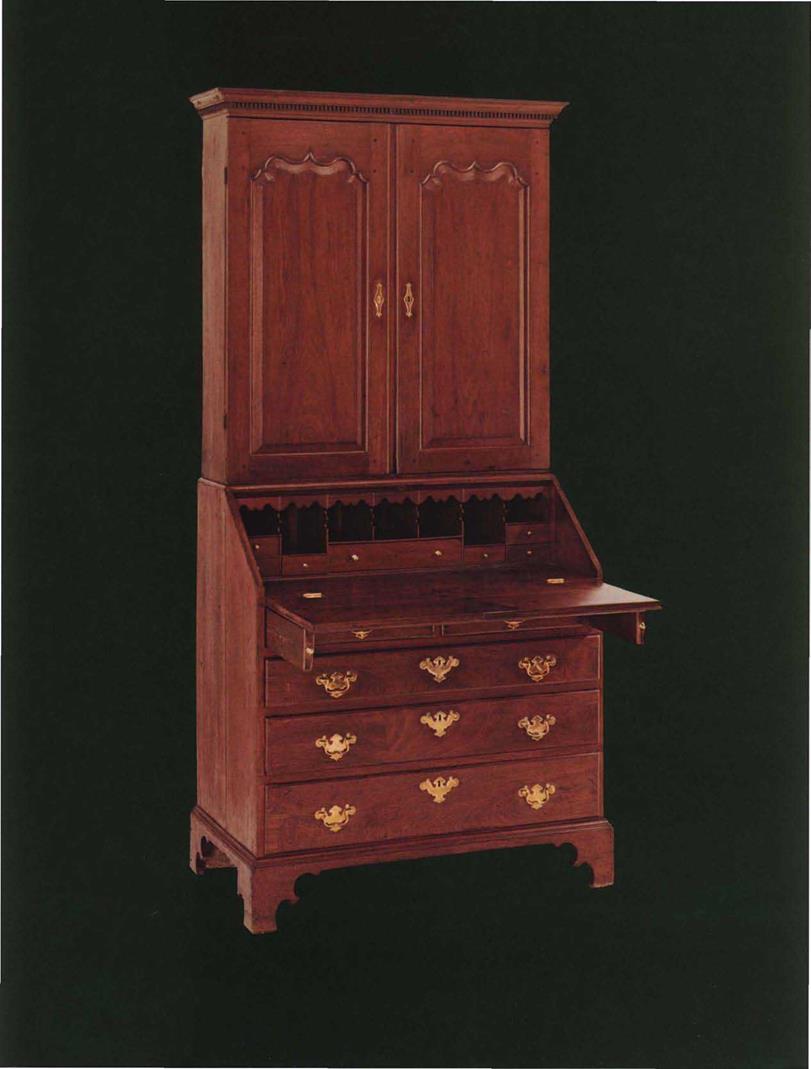

There is a large corpus of Williamsburg furniture that cannot be assigned to specific shops based on present knowledge. This includes single items and small groups, some having details or construction that suggest one of the two shops already isolated in this study.

One of the most intriguing pieces in this study is a side table fashioned of black walnut (fig. 93). It has legs carved as three clustered columns and a skirt pierced in abstract rococo designs. The unusual rabbetted edge of the top, which is an old replacement, is identical to the Palace tea table and also incorporates indented corners. This was neither a logical nor an attractive design, and it appears that the restorer was copying the original, which, unknown to him, had lost the applied molding that formed a tray top. This modern rabbet does not continue around the table as it would have on the original. It is unexpected to find that the back skirt is unfinished pine.

One of the most intriguing pieces in this study is a side table fashioned of black walnut (fig. 93). It has legs carved as three clustered columns and a skirt pierced in abstract rococo designs. The unusual rabbetted edge of the top, which is an old replacement, is identical to the Palace tea table and also incorporates indented corners. This was neither a logical nor an attractive design, and it appears that the restorer was copying the original, which, unknown to him, had lost the applied molding that formed a tray top. This modern rabbet does not continue around the table as it would have on the original. It is unexpected to find that the back skirt is unfinished pine.

In addition to being associated with the Palace tea table (fig. 57), this table is tied stylistically to a large number of W illiamsburg pieces. The central piercing immediately beneath the top, and the pair of small vertical piercings in the skirt are quite similar in concept to those in the crest and splat of a chair from the Scott shop (fig. 30). The inverted arches on the tops of the table legs point dow nw ard between the columns and therefore are similar to those of the following table (fig. 94).1 The through-tenoned cross stretcher and the continuous chamfers, which continue to the table top on the inside of the legs, are seen on a number of Williamsburg chairs (figs. 95-97). It is also stylistically related to the china tables attributed to Bucktrout, with their piercing and heavily sculptured legs—features that are otherwise extremely rare in Virginia-made furniture.

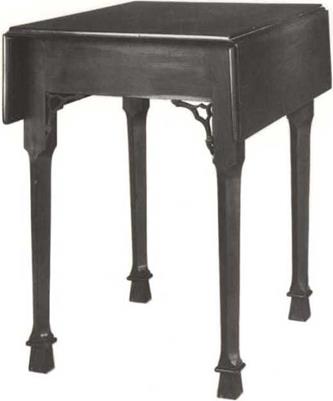

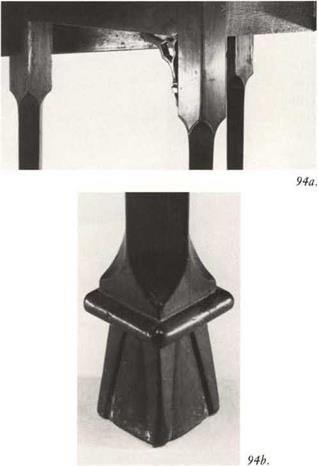

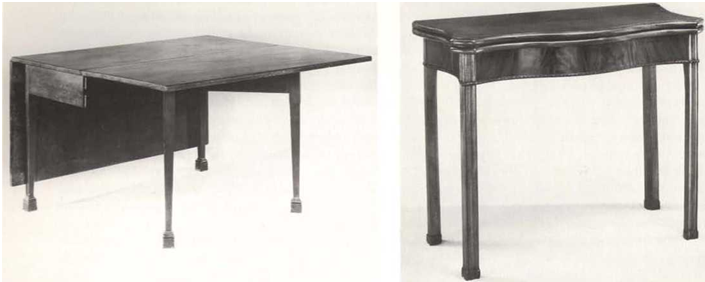

Boldly carved gothic style legs distinguish the follow ing breakfast table (fig. 94). Phis form, know n in the eighteenth century as a Pembroke table, is documented in Williamsburg before 1780 when Richard Booker, a local cabinetmaker, made one for Col. John Prentis.2 The example show n here, w hich descended in the St. George Pucker family of W illiamsburg, is made of dense mahogany with oak and yellow pine. Each leg has a small bead near the skirt that apparently continued onto the original brackets (unfortunately now missing, see fig. 94a) and across the apron. These brackets were relatively large, and evidence suggests that they were higher than they w ere w ide. No Williamsburg parallel to the carved foot is known (fig. 94b), although “shifted square” legs of this type are found on several pieces attributed to northeast North Carolina.3 Their pre-

|

|

94. Pembroke Table, Williamsburg, circa 1775. Mahogany primary; oak, yellow pine secondary.

Height 28Ve", width 26Vi", depth 34’A" open, 19 Vi" closed. Dr. Janet Kimbrough.

rise origin and their relationship to this table deserve further study.

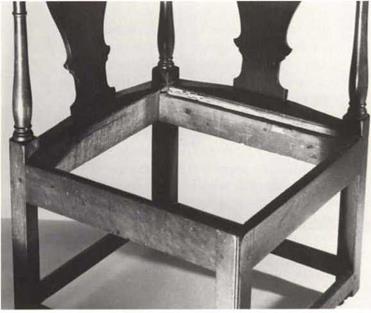

The next three chairs (figs. 95-97) were undoubtedly made in a single Williamsburg shop and are representative of a large group there. Most are very plain, but the Hnest example (fig. 97) has a pierced splat and beaded edge on the back. The most characteristic feature of this group is an unusual splat attachment. The splat is not seated in a separate shoe in the usual fashion but was nailed into a large notch on the inside of the rear rail. The notch was then filled with a secondary wood, usually pine (visible on the left rear rail of figure 96a). On corner chairs in this group the notch is normally covered on the right rail with a slip seat support made of pine. The chamfered corners on chair legs run completely to the top of the seat rail rather than stopping just below it in the usual manner.

A simple side chair is one of a set of four that descended in the Galt family (fig. 95). A pair of slipper chairs also belonging to this group were in the same household (not pictured). The ownership of these two sets of chairs in the Galt family of Williamsburg, and the corner chair that descended in the St. George Tucker family there, constitute the nucleus for attributing this group to a Williamsburg shop. Additional support for the attribution to Williamsburg is found in other related pieces—a side table (fig. 93), a corner chair (fig. 28), side chairs (figs. 98-100), and an armchair (fig. 101).

The lone corner chair illustrated from this group (fig. 96) also has a history in the St. George Tucker family. The splat design is related to the type found on a Scott corner chair (fig. 28). Five other corner chairs from this group are pictured in the MESDA files, and three of these have an unusual crest and arm construction related to two Scott corner chairs (see figs. 28, 29 and pp. 36-38 for comparative discussion). One of these five chairs has the same splat design as this one while the other four have extremely simple splats identical to the Galt family slipper chairs (not illustrated). Two have turned columns similar to those shown on this example (fig. 96) and the others have extremely simple columns without molded bases. The turning is abruptly ended at the base leaving sharp corners—a feature also seen on several Scott examples (figs. 28,29). One of these appears to be considerably later than the others and has heavily tapered legs in the federal style. These five chairs have widely scattered histories in areas to the north, northwest, and west of Williamsburg.

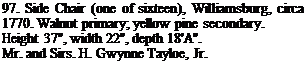

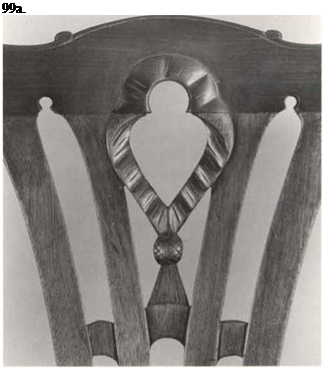

A set of sixteen chairs from this group (fig. 97) are original furnishings of Mount Airy, the fine – country house of the Tayloe family. These have the

|

93. Side Chair (one of four), Williamsburg, circa 1770. Walnut primary; yellow pine secondary. Height 37 ‘A", width 19’A", depth 16". The Anne Galt Black Collection. |

unusual splat attachment seen throughout the group, but two departures distinguish them: the chamfer on each leg stops just below the seat rail, rather than continuing upward; and they have “H” rather than box stretchers.

In spite of these slight departures from the simpler examples, the Mt. Airy chairs are closely related and probably represent the same shop. Their refinements offer an important opportunity to understand two different levels of quality from a single shop and, by extension, a better understanding of eighteenth-century chair usage. In addition to the H-stretchers, they have more elaborate backs. When compared with others in the group that have less detailed backs combined w ith box stretchers, they strongly support the conclusion that those w ith box stretchers were considered a modest form.

96. Comer Chair, Williamsburg, circa 1770.

Walnut primary; yellow pine secondary.

Height SO", width (across arms), 29 Ун", depth (front leg to back column) 26", seat І8Ун"square.

Dr. Janet C. Kimbrough.

Dr. Janet C. Kimbrough.

|

|

|

||

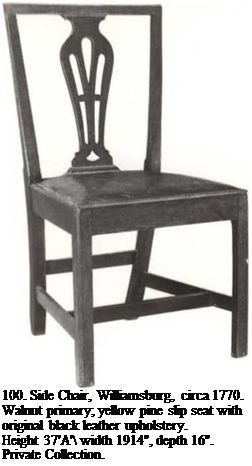

Four chairs that display some consistency of design and construction (figs. 98-101) share features with the last group but clearly come from a different shop. Their splats have normal construction and arc mortised into a separate shoe glued to the rear seat rails. The double blocks on the interior corner of the seat frames overlap each other—a construction often thought to come only from Philadelphia, although its origin is actually England. The crossbar of the U-stretchers are half-dovetailed into the sides and enter from beneath, which differs from the preceding group.

One of these side chairs (fig. 98) is a single surviving example from a large set owned by the Galt family. It has a crest rail and delicate bead carving similar to those seen on a chair in the last group (fig. 97). The splat design w as popular in England and America, but those made in Williamsburg are distinguished by the addition of trefoil piercing and a tassel. A virtually identical pair of mahogany chairs in the Colonial Williamsburg collection (fig. 99)

One of these side chairs (fig. 98) is a single surviving example from a large set owned by the Galt family. It has a crest rail and delicate bead carving similar to those seen on a chair in the last group (fig. 97). The splat design w as popular in England and America, but those made in Williamsburg are distinguished by the addition of trefoil piercing and a tassel. A virtually identical pair of mahogany chairs in the Colonial Williamsburg collection (fig. 99)

appear to be products of the same shop, but they are embellished with the addition of carving. All of these examples have yellow pine slip seats and two of them (figs. 98, 100) have the original upholstery. On the black leather of these examples is a fine, hatched design that appears to have been impressed or stamped into the leather. Unfortunately the design is badly worn and remains visible only on the protected underside of the seat.4

Quality and construction place another Galt family side chair (fig. 100) w ith these examples, even though its splat and crest rail are virtually identical to those of the preceding group. In addition to the constructional association, the upholstery technique of this chair is identical to that of figure 98. Significantly, it is upholstered by a completely different method from that employed in the Palace set (fig. 67): it does not utilize a long tab pulled over each corner anti the leather w as cut so sparingly that it w as pulled over the slip seat frame and nailed near the outside edges.

The last piece in this small group is an armchair that bears the deeply impressed marking “VIRGA” on its rear seat rail and has a tradition of use in the Virginia 1 louse of Burgesses (fig. 101). The back is w ell designed, and, to the know ledge of the author, unique. The crest rail, the carved “loops,” and techniques of construction place it firmly in this group. The carved foliage in the splat, like that of the carved ribbon and tassel in figure 99, has a completely different character from products attributed to the Scott and I lay shops. Likew ise, the extremely rigid qualities of the narrow scroll borders on the crest, splat, and stiles differ from I lay shop chairs (figs. 59, 62). The lack of molding on the top of the seat rail seems slightly incongruous w ith its elaborate back, but this feature is seen on pieces made by Peter Scott and on a corner chair in the preceding group (fig. 96). The arms of this chair may be eighteenth – century replacements, since they interrupt the stile molding in a very heavy-handed manner, w hich is hardly consistent w ith the character of the back. Examination of the arms resulted in no other evidence of replacement, and the signs of wear are extremely convincing.

The mark “VIRGA” found on this chair is intriguing and raises several questions. Although the piece has a vague history of usage in the House of Burgesses at the Capitol, w hy w as it stamped when others from there (figs. 7, 46) were not? It seems logical that the circumstances necessitating such marking would have been followed throughout the building and two unmarked examples used in the Capitol seem to remove this chair from consideration as a furnishing there. With the Capitol eliminated,

The mark “VIRGA” found on this chair is intriguing and raises several questions. Although the piece has a vague history of usage in the House of Burgesses at the Capitol, w hy w as it stamped when others from there (figs. 7, 46) were not? It seems logical that the circumstances necessitating such marking would have been followed throughout the building and two unmarked examples used in the Capitol seem to remove this chair from consideration as a furnishing there. With the Capitol eliminated,

the most logical building for such a chair would be the Governor’s Palace.

Circumstances at the Palace were quite different from those at the Capitol. As a residence, it was not furnished solely by the colony but had a number of items belonging personally to the Governor. Furniture owned by the colony was termed “standing furniture” and in the inventory of Lord Botetourt’s estate, taken in 1770, it was listed separately from that owned by the Governor. While it is not known whether standing furniture was marked, the advantages of doing so are obvious, for over 16,500 objects were listed in the Palace at the time of Botetourt’s death. Additional support forthis conclusion is found in an early order from the Council, specifying that new muskets for the colony be marked “Virginia 1750.” This evidence is further reinforced by the lack of identifying marks found on any of the eighteen pieces with a tradition of ownership by Lord Dunmore. Hopefully future research w ill clarify the history of this chair, but for the moment evidence suggests that it was made as standing furniture for the Palace.

Among the pieces of furniture attributable to W illiamsburg are a number of six-legged dining tables, a type that w as produced over a wide area of eastern Virginia and northeast North Carolina. The form is apparently Knglish in derivation and dates from the mid-eighteenth century. These tables have three legs at each end w hen the leaves are down—a stationary one in the center and a movable one on each corner. They arc very practical, allow ing more adjustment of the legs for seating and providing superior stability. Two six-legged tables of this type are known to have descended in Williamsburg families: a straight-legged example and one w ith pad feet (fig. 102).

The latter piece is made of mahogany with yellow pine and oak, and it has a variation of the high trumpet-shaped pad feet associated with the I lay shop. Several other mahogany examples that closely correspond to this are known, and many straightlegged pieces are made of walnut. Several with ball-and-claw feet come from northeast North Carolina.

104b.

One handsome variation of this unusual type is found in a dining table made of mahogany, with oak used as a secondary wood (fig. 103). I lere the fixed central leg has been omitted, leaving only’ a hinged one on each corner. Three such tables w ere original furnishings of Mt. Airy. Two are still used there and a third from the ensemble, though damaged, survives. It should be noted that these examples may represent Knglish production, since they use oak solely as a secondary wood. Traditionally this has been accepted as indisputable proof of Knglish origin, but many eastern Virginia tables have oak in their gates, although pine or w alnut is usually found in the secondary rails. Considering the profusion of English-trained cabinetmakers in eastern Virginia, it

would be a mistake at this point to preclude that they represent Williamsburg production.

A serpentine card table is the last Williamsburg example in this study (fig. 104). Found in the Petersburg area about fifty years ago, it is related to several pieces from the 1 lay group, although it is sufficiently different to make a more specific attribution uncertain at this point. Made of mahogany and mahogany veneer, it has heavy poplar rails while the remainder, including the swing gate, is yellow pine. The egg-and-dart molding around the skirt (fig. 104a) is related to that on the underside of the arms from the Bucktrout chair (fig. 49d). In both examples, the carving is stylized and shows a degeneration of the academic prototype from which it originated. I he character of this degeneration is essentially the same in both examples and suggests a connection between them. The misunderstanding occurs principally in the design of the dart element between the eggs: this area is simply cut away, leaving the projections extending beneath the eggs looking very much like flower petals. The w ell formed block feet are mortised onto the leg with a through tenon that is rounded on the bottom. One block is somew hat loose and cannot be turned, which probably means that the round section projects beneath a square tenon.

With these pieces the study of Williamsburg cabinetmaking is concluded. Five distinct groups have been analyzed, as well as many other pieces that bear a close relationship to them. Unquestionably, the Peter Scott and Anthony I lay shops dominated the volume of production, and many examples dating from the period 1765-75 show stylistic and constructional affinity to their work. By that decade a number of other cabinetmakers had appeared in the area. William Kennedy, John Crump, and Richard Booker have already been mentioned, but others include Archibald Marrocks (1776) and James Honey (1776-K4); Matthew Moody (1766- d. 1773); Thomas Orton (1768); John Ormeston (1761-1766); James Tyrie (1772-84); and Widdatch & Drummond “Near Williamsburg” (1764). Some of these served apprenticeships under earlier masters, thereby extending the practices anti designs of existing Williamsburg shops. Others, aided by the turnover of journeymen, contributed to changes in established styles. The influence of workmen with various training encouraged the combination and recombination of the old with the new, and they mixed their results w ith ideas flowing from Kngland or with those drawn from Chippendale’s Director or Household Furniture. This interchange of technology and style, combined w ith a parallel development of the taste of patrons, is in essence the process by which the Williamsburg “school” w as formed.

There are still many questions to be answered and further research is needed to clarify the contributions of cabinetmakers w ho worked in Williamsburg in the late colonial period. Did cabinetmaking there evaporate abruptly when the capital moved to Richmond in 1780? Or did patronage established in the colonial period keep the shops of Bucktrout and others busy, continuing their production into the neo-classic style? The post-colonial pieces shown in this study have been included to point out the serious need for documentation of Williamsburg and eastern Virginia furniture in the federal period.

In conclusion, cabinetmaking in Williamsburg during the eighteenth century exhibits a tremendous variety, from average or modest examples to the remarkable and unique, from bold or massive pieces to light and delicate ones. The finest achievements of the cabinctmaking trade in Williamsburg, like those of the society in which it flourished, were founded on sound principles and philosophical ideals that enabled cabinetmakers to excel tar beyond the limits expected of so small a city.

FOOTNOTKS

1. A tabic recently examined by the author has legs that are nearly identical to those of the Pembroke table depicted in figure 94. It also has pierced cross stretchers, with a design closely related to the heavy piercing on the skirt of the tea table shown in ligurc 93, thus strengthening its association with both of*these pieces. It has a history in Nottoway County.

2. Mills Brown, "Cabinetmaking in the Kightccnth Century" (unpublished research report. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia, 1959), p. 150.

3. Helen Comstock, “Furniture of Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, and Kentucky," The Magazine Antiques 16 (January I952):97, tig. 155.

4. This stamped black leather is possibly the same material referred to in the account book of Alexander Craig, a Williamsburg harness-maker and tanner. (Craig Account Rook, Manuscripts Division, Earl Gregg Severn Library, College of W illiam and Mary, W illiamsburg, Va.) Craig is known to have sold "black grained leather" at £1 per hide to a number of Virginia cabinetmakers, including several who lived some distance from Williamsburg. Among them were John Scldcn of Norfolk and James Allen of Fredericksburg. Since other hides were undoubtedly available from tanneries located much closer to the artisans, those supplied by Craig must have had special qualities, probably their stamped graining. The expense, combined with the fact that these hides were sought by distant patrons who had to pay the additional cost of transporting them, supports this conclusion. Craig Account Book information courtesy of Harold B. Gill, Jr., historian. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

|

|