Do typical woodland fauna emerge in isolated urban-industrial woodlands? This question is addressed here using ants and ground beetles as indicator groups. The species composition in both groups shows significant differences between the pioneer, shrub and woodland sites (Figs. 6, 7). Generalists and species of dry, warm and open habitats dominate in the early stages. They are still present in the woodlands, but here, typical woodland species begin to dominate.

|

|

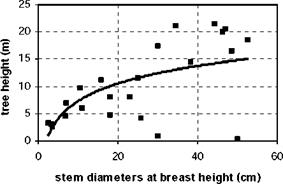

Fig. 5. Height versus diameter at breast height of Robinia pseudoacacia in an 80- to 90-year-old black locust stand at site WZ

There are obvious differences in the species richness of the two woodland sites. At the birch site WR, 14 ant species were found (12 with evidence of nests), at the black locust site WZ only 6 (5 with evidence of nests). Common species that are typical of the top layer of litter, such as Stenamma debile, are missing. Only three species of ground beetles were recorded at WZ over the three years of investigation. Two of these are typical woodland species that are capable of flying (see Table 4), the third is a xerophile species typical of open habitat conditions (Harpalus ru – bripes), and represents by far the most individuals. At the birch site WR, 11 ground beetle species have been recorded. Seven of these prefer woodlands, and they make up the majority of the individuals.

The differences between the two woodland sites may be due to the fact that site WZ is more isolated than site WR from old parks and remnants of the traditional open landscape. At WR, two of the woodland species are unable to fly (Carabus nemoralis, C. coriaceus), which results in reduced opportunities to colonise isolated habitats. In contrast, the two woodland species found at WZ were small and able to fly (Table 4). For ants, however, isolation is of less importance, because sexually mature individuals can fly. The low species richness at site WZ may be due to the low occurrence of greenflies (aphids) in the Robinia stands. Here, this important food resource of ants is confined to Sambucus nigra and Acer pseudopla – tanus.

|

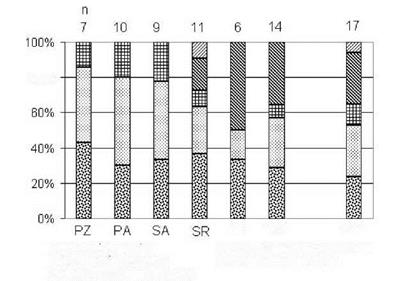

Fig. 7. Proportion of different ecological groups of ground beetle species in pioneer, shrub and woodland plots (for abbreviations see Table 1). The results are the summary of data for 2000, 2001 and 2003; n indicates the total number of species

Fig. 7. Proportion of different ecological groups of ground beetle species in pioneer, shrub and woodland plots (for abbreviations see Table 1). The results are the summary of data for 2000, 2001 and 2003; n indicates the total number of species

Conclusions

Hard coal-mining spoil as soil parent material leads to extreme habitat conditions. The soils are very gravelly, stony and poor in fine earth and nutrients. Except on sites with fresh depositions of spoil, pH values are very low, which frequently increases the availability of heavy metals. This leads to slow migration of soil fauna and to slow decomposition of litter and soil development. Under these conditions, new types of plant communities arise on the post-industrial sites. The pioneer communities are usually rich in species that originate from a broad array of habitats (ruderal and salty habitats, river banks, arable fields, grasslands) or that were introduced from other regions. The comparison of different-aged sites shows that species richness will decline during succession. This also holds true for endangered early-successional species (Rebele and Dettmar 1996, Weiss and Schutz 1997, Weiss 2003b)

On the other hand, woodland species, both plants and animals, begin to colonise young woodland sites that are still dominated by pioneer trees such as birch and black locust. Examples include tree species (Quercus ro – bur, Acer pseudoplatanus, Carpinus betulus), fern species (Athyrium filix – femina, Dryopteris filix-mas, D. carthusiana), and ground beetles (Cara – bus nemoralis, C. coriaceus). Differences between the plots may be attributed to isolation effects and to different food resources in stands of native (birch) versus non-native (black locust) tree species. In both woodland plots, early – and late-successional plant and animal species occurred together. This may be due to the immaturity of the woodlands and to their close connection to open habitats which is characteristic of urban-industrial woodlands. Similar results have been found when comparing the different succession stages of a derelict railway area in Berlin (Platen and Ko – warik 1995). Further research will reveal whether the co-existence of different species groups remains a feature of the studied woodland communities.

A second open question is that of the direction of woodland succession. Late-successional tree species such as Acer pseudoplatanus or Quercus robur are already established under the canopy of birch – and black locust – dominated stands. It is doubtful, however, that these species will quickly outcompete the pioneer tree species. Obviously, the extreme soil conditions of the hard coal-mining spoils will remain unchanged for a long time. This may reduce the growth and competitiveness of species such as Acer pseudoplatanus. In the black locust stand, some of the taller trees have begun to die. This enhances the establishment of other tree species, but vege-

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

tative regeneration of black locust also occurs in such stands and may prolong the predominance of the North American species (Kowarik 1996).

In addition to natural processes, the undirected succession of industrial abandoned land will be differentiated by the recreational activities of local people who make use of these new types of woodlands (Keil 2005). The quality of these sites is mostly due of the diverging patterns of pioneer, shrub and woodland stages and to the remnants of the industrial history. Thus, concepts for developing this post-industrial landscape should combine approaches that both enhance wilderness and maintain open habitats and cultural remnants. This is the main idea of the Projekt Industriewald Ruhrgebiet, which aims to enhance the social and ecological functions of the urban-industrial woodlands (Weiss 2003b, Dettmar 2005).