… the outdoor clay oven is full of flame, stoked with dry sticks collected in the woods; next to it the bread made from the wheat from our ‘field’ in the garden is rising. In the classroom the jam made from the hedgerow blackberries in September is being brought out; and butter made from cream from the local farm, is being salted and put into dishes. Bottles of apple juice made in September and stored in the freezer are being defrosted. Class three will celebrate the end of the term’s farming work with a jam sandwich and a glass of juice, won by the sweat of their brows 58

In contrast to the approach taken by ‘Focus on Food’ in the UK, the growing schools and edible school yard movements are conscious of the importance of teaching, through experience, that food does not originate in the supermarket, but in the soil through labour and care. The schoolyard projects discussed here position themselves as part of a wider movement towards building sustainable communities. There is an important difference between learning to cook dishes from different parts of the world from recipes provided and learning the cultural significance of food from and alongside members of the local community. Until recent times, the skills and knowledge about the production, preparation and presentation of food were learnt within an oral culture, primarily in the home or wider community. To replicate and rescue some of that traditional understanding around food in schools, the emphasis is placed on learning through experience. The land and the local community provide inspiration and resources in an approach which prioritizes respect, tenureship and collective endeavour.

‘From working to learn to learning to work’, the outdoor classroom is an extension of the ‘main lesson’ in a Steiner school. The philosophy which underpins the educational landscape of the Steiner or Waldorf school is one that views the child in its early stage of development in becoming human as the embodiment of an early stage in the general evolution of humanity. From this perspective, the young child might be viewed as a natural ‘hunter – gatherer’ within a primeval landscape. Within such a philosophical framework, work with the brain is viewed as inseparable and of equal value to work with the heart and work with the hand. This has not been the case within the dominant paradigm of school which has come to regard the academic as superior to the practical and the pursuit of intellectual knowledge and skill as more valuable than the passing on of traditional wisdom about domestic husbandry.

Recognition of the circle of the year through its changing seasons requires a flexibility of human response if the natural powers of sun, wind, earth and water are to be orchestrated to fulfil human needs. Teaching and learning according to the circularity of the turning seasons brings those involved face to face with the consequences of their previous endeavours. In contrast, the dominant ideology of mainstream schooling is linear; children and young people move on and away from their previous work. Once complete, the work may or may not be celebrated. Most likely it will be measured according to values and standards externally derived and enforced. Most significantly, the child learns in school that work carried out rapidly takes its place in the past; to revisit the very same site of work represents failure, the danger of falling behind, or enforced punishment. Some would argue that the lesson taught is ‘detachment’ from the content of learning.59

Such a ‘seasonal pedagogy’ contrasts and clashes with an ‘industrial pedagogy’ in many ways. A ‘seasonal pedagogy’ challenges expectations about the landscape and ecology of school. The urban school building and environment took on an established form in the industrial era, rising from its roots in the workhouse and the factory.60 The concept of progress accompanying the establishment of mass education in European countries and the United States led to the establishment of a uniformly bounded environment, an urban ‘island’ of childhood even in a rural location.61 It was an avowed part of the project of national mass education to frame the school alongside the church as the only sites of generating and transferring valuable knowledge within a community and particularly to disassociate wisdom from the domestic arena. Even in the inter-war period in England, while gardening was part of the curriculum, it was forced to take place outside of the school boundary within which was built the ubiquitous asphalt schoolyard.62 In the mainstream, schools generally became hard environments, the outside spaces conducive to ball play, drill and physical exercise. The rise of competitive school sports in the grammar and high schools helped preserve some green areas but even these have in recent years been sold off by many schools struggling to survive under restricted budgets. Strongly established in the popular concept of school is the familiar building situated within a neatly kept, bounded territory which speaks of academic rather than agricultural labour and achievement.

A ‘seasonal pedagogy’ contests the traditional management of time and the organization of the school day, week, month and year. The growing season presents the opportunity and the necessity for a great deal of active engagement with the land in the spring and summer while there is much less activity during the winter months. Although the turn of the year is predictable, the weather and conditions are not and activity needs to be flexible in response. At peak growing times, the growing plants dictate what activity is needed where and when. The same tasks need to be repeated throughout the seasons; the efforts of one year are recognized in the next and the effect in reality is cumulative. ‘The picture varies from year to year; it evolves and changes’.63

The transformation of schoolyards in the Berkeley school district of California has its origins in the efforts of Robin Moore who led the landscape architecture school at the University of Berkeley.64 In 1980, Moore saw the potential for using the outdoor environment of schools to enliven children’s learning experience, teach sustainability and encourage community involvement.

The space was a desert of asphalt, so typical of many school yards. But by asking people what they liked about the yard, and what they wanted to change, …the yard is becoming a place where community and school can meet.65

Washington School yard, a one and a half acre site within a high density urban neighbourhood became the best known example of school ground revitalization in North America and inspired other projects. The food garden was one of a number of features that included a natural play area. This project established what could be achieved and inspired others. Two decades later, it is still a vibrant, living and utilized feature of the landscape of the school (see Plate 20).

The district of Berkeley is a short distance across the bay from San Francisco. It has a lively, young, diverse population with the University of California campus at its heart. The movement for organic and whole foods took root here during the 1970s and 1980s and it is possible to find the widest possible choice of high quality, fresh local produce in the regular farmers’ markets or the vast food stores. Cafes, restaurants and bistros serve foods in the traditions of every part of the globe. But most children who attend the public schools are accustomed to fast foods such as TV dinners and are used to a poor or non-existent diet. Nevertheless, the cultural climate in Berkeley has motivated the community to support initiatives around transforming the edible landscape of school. In August 1999, Berkeley School Board in California set in motion a revolution in the place of food within schools. After a decade of anxiety fuelled by scientific speculation about the impact of pesticide residues on fruits and vegetables consumed, together with the introduction of genetically altered foods, and the ever increasing fast food market, the pressure was on for a change. Parents and teachers, and some food specialists including Alice Waters, a well-known local chef and restaurant owner, campaigned for change. A three – year campaign in association with the Food Systems Project of the Centre for Ecoliteracy, including fundraising, finally brought success. As well as the introduction of organic produce, the Berkeley school district plan has banned the use of genetically engineered or irradiated foods and dairy products from cows injected with the recombinant bovine growth hormone. Other goals of the district’s plan include establishing a child nutrition advisory committee and eliminating food additives and high-fat, high-sugar snacks available in school. Schools are directed to serve tasty, fresh, local and organic foods in ways that reflected the districts’ ethnic diversity.

It is intended that all sixteen public schools in the district will have gardens used by teachers and pupils as open air classrooms and sources of food for the school lunch, and the whole philosophy is to have food become a central part of education. An integrated curriculum which promotes awareness of the way food is grown, the environment, and health is the central plank of the policy. The further development of the policy is managed by The Berkeley Food Policy Council, a coalition of residents, non-profit agencies, community groups, school district and city agencies formed in May 1999. It is pledged ‘to build a local food system based on sustainable regional agriculture that fosters the local economy and assures all people of Berkeley have access to healthy, affordable and culturally appropriate food from non-emergency sources.’66

The edible school yard is an organic garden and kitchen non profit-making-project that integrates the curriculum and lunch programme at Martin Luther King Junior Middle School in Berkeley, California. The school serves a very diverse community – the majority of the 820 children are of non-European origin. A large proportion are from impoverished backgrounds. Most parents work and children rely heavily on ready-prepared fast food. Few have garden plots of their own at home. From the start, the project had the backing of celebrity chef Waters whose prominence in the project helped to secure financial support which now amounts to some $400 000 annually, most of which pays for the salaries of six full-time workers. It also pays for half of the time of a science teacher in school who works on the project. One hundred tons of compost from the City of Berkeley helped to start the one acre plot in a raised area above the main asphalt yard of the school. Started in 1995, pupils, parents and teachers together transformed the playground area into a beautiful vegetable, herb and flower garden. The style is organic: a wide variety of vegetables and fruits complemented by

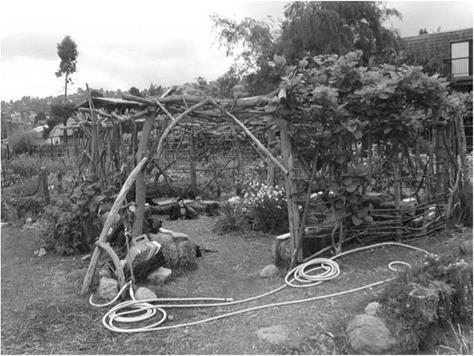

flowers and herbs. The children have constructed the boundaries, the fences and scaffolding out of natural materials. There is no fence surrounding the garden which is open at all times for the community to visit and admire (see Plate 21).

Very little vandalism has occurred as the entire garden is cared for by all pupils and their sense of ownership is strong. Involvement in the garden begins with the youngest grade six children who enjoy harvesting, roasting and eating corn using the garden oven. This establishes the principle of the garden landscape, that food comes from the ground and working with it is fun and satisfying. A ‘scavenger hunt’ follows and children are encouraged to experience for themselves the sights, smells, textures and sounds of the garden. Thereafter, each ninety-minute ‘lesson’ starts at the centre of the garden in the open air classroom, a circular arrangement of branches woven together to form a kind of dome.

|

|

On a rotational basis, each grade works in the garden or the kitchen over three-week intensive ninety-minute periods, a total of three hundred children each week throughout the year. After

school classes are available and a summer programme, free of charge, is also provided covering garden and kitchen work.

During six days of annual statutory testing, the edible school kitchen prepares and serves a nutritious and delicious breakfast to children free of charge. Out of the full number of 820 pupils currently registered, the breakfast is voluntarily taken by around 300, a few minutes before their tests begin. The idea behind the breakfast is that the children are likely to perform better in the tests on a satisfied stomach. The 300 who take the offer of the breakfast could be an indication of the approximate number regularly coming to school on an empty stomach. The breakfast consists of something hot, for example, on a particular day that might be oatmeal, macaroni cheese, or scrambled eggs, served with a chunk of wholesome organic bread (provided as a donation by a local bakery), a full piece of fruit and milk. Everything is prepared fresh on the morning and is served in an informal atmosphere of respect, enjoyment and celebration.

Children relish these breakfasts and are overheard to say they regret the end of the testing

period. If funds allowed, the project would like to provide such breakfasts during the whole school year. More generally, classes are held in the edible school kitchen. As many ingredients as possible are harvested straight from the school garden, the rest provided by local organic farmers’ markets. Some of the ingredients such as lentils or rice may be prepared in advance so that the children can work with the raw foods, preparing and cooking them in the short time period available. Any brand labels are removed as children are led to focus on the value of working with locally harvested foods. After the cooking is complete, the tables are set by the children and they sit to eat their meal together.

|

|

One thousand miles north of Berkeley, just over the border into Canada is Vancouver, with a distinctly cooler climate but an equal passion for schoolyard revitalization. Here, Gary Pennington, while Professor of Education at the University of British Columbia, started the first school food garden in Vancouver. Built in 1989, the food garden was part of a larger project at Lord Roberts Elementary School in the West End of the City, Canada’s highest density neighbourhood. The predominant type of residence is high rise and

consequently there is very little garden space available to the community. In its early days, Pennington said of the children ‘the food garden increases their sense of wonder. It’s pretty magical, but at the same time, it demystifies the concept of food production’.67

The garden at Lord Roberts Elementary still exists and has laid the foundations of other schoolyard revitalization projects. Evergreen, a Canadian national non-profit environmental organization sponsors and promotes through its ‘Learning Grounds’ programme the transformation of barren school grounds into dynamic natural outdoor learning environments. A special emphasis is placed on participative and democratic planning. The design process starts off in the classroom where children are encouraged to dream up their imagined ideal schoolyard. The next stage involves the children and teachers surveying the land and drawing up practical possibilities. An important part of the learning process is around negotiating possibilities within the boundaries dictated by physical, legal and customary features.

One of the most adventurous projects carried out through a participative design process is found in a disadvantaged multicultural inner city community in Vancouver.

Grandview Uuqinak’uuh is an inner city elementary school in Vancouver’s East End. Built in the 1920s, the school accommodates a culturally diverse community. More than half of the children who attend and a core of teachers and learning assistants are of ‘first nations’ ancestry. This strong cultural context is supported by several first nation housing projects in the neighbourhood. Communities from Eastern Europe, China and Vietnam are also served by the school. Over 90 per cent of households are headed by single mothers. This rich cultural heritage is embraced in a school community which is determined to challenge the deprivation and associated levels of crime and disaffection in this neighbourhood. The school gardens were designed to be the ‘backyard of the community’ since so many of this community living on the margins do not have access to garden space.

Three years ago, the grounds were dirty and dangerous as some members of the community used them for recreational purposes leaving litter behind. A vast open space was transformed into ‘a more beautiful, useable and sustainable space where children and the community can learn.’68 The design emerged out of a process of gathering ideas from workshops and open houses with staff, students, parents and other members of the community. Many of the original ideas came through to the final design and parents, teachers and children together constructed the garden beds and helped to construct and decorate the outdoor classroom.

The school has been renamed in the Nuuchahnulth language, Uuqinak’uuh meaning ‘beautiful view’ and the school day begins with the beating of a drum. The design of the school garden is reflective of the character of the school and the ‘voice’ of the community and there was, from the start, good support for aboriginal design elements among the teachers.

This diverse community is invited directly in to the school ground by means of renting a small garden plot within a larger space of raised beds. The layout is formal and contrasts with the organic, informal style found in Berkeley. This was a design requirement of the community, a direct response to the fear voiced by the community that the gardens would look messy in winter.69 It seems, from the final design, that the needs of the adult members of the community, teachers, staff, parents and others overruled some of the most popular ideas for the garden voiced by the children. The most favoured design idea of the children was for a waterfall followed by a stream or creek, and growing flowers and vegetables was prioritized. In the final gardens there is no water feature as adults feared that this might encourage drug use.

Cooking ‘fun for family’ classes are held on a weekly basis. First nations and Vietnamese parents and children enjoy learning and eating together during these classes. Several times a year, cultural social events featuring food and dance are held. Hot breakfast and hot lunch programmes are used by the majority of children.70 The children’s food garden is also set out in wooden framed raised beds constructed by the children with the help of parents and teachers. Corn, tomatoes, radishes, carrots and lettuces are grown but the size of the vegetable gardens is inevitably limited by the commitment of parents and others in the community to share their labour freely. The original idea of growing ample food for the lunch programme in at least one season has been compromised. However, the butterfly and bird habitat has been planted with edible fruits and berries that can be grazed by children in season. Once an area prey to drug trafficking and prostitution, the school has transformed a recreation field into a vibrant open air inter generational classroom.