Whilst investigating aspects of the learning environment, we found relationships between behaviour and human experience on the one hand and the design of the physical setting on the other.38 It is a complex relationship and evaluation naturally incorporates a degree of personal interpretation. The most common method used in qualitative research is participant observation, which entails the sustained immersion of the researcher among those whom he or she seeks to study, with a view to generating a rounded, in-depth account of the group. Behavioural mapping has been the key tool in this study, together with key research questions which have been addressed to those teachers involved.

Behavioural mapping is a form of direct observation, tracking the movements of subjects through existing physical settings, whilst observing the kinds of behaviour that occur in relation to these settings. It is empirical, describing observed behaviour both quantitatively and qualitatively. There are three components to this: the description of the environmental setting; the description of the subject; characteristics and the description of the behaviour.

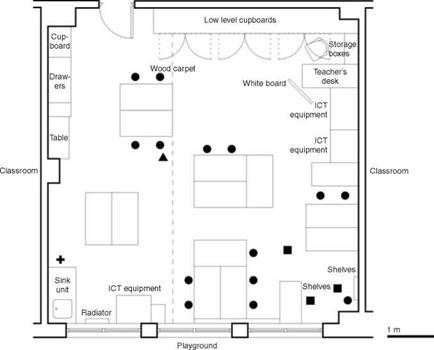

Behavioural mapping is a naturalistic time-sample technique for describing patterns of activity and the use of the physical space. A scaled drawing or a floor plan of a physical space provide the basis of the observational studies, with each area labelled according to the kinds of behaviour expected to occur there. The research refers to classrooms built within the existing building stock. The main body of the research refers to Key Stage 2 classrooms, which accommodate children aged between 7 and 11 (in year groups 3 to 6), exploring the relationship between the classroom environment and the implementation of the National Curriculum.

The study’s initial research questions provided the structure for the research methods applied. The prime research question is:

How does the physical environment of the primary classroom influence the effective delivery of the National Curriculum?

From this, five sub-questions can be extracted to determine the parameters of the research. These questions are associated with the classroom environment, teaching and learning, physical organization, and the final question concerning the implications of the study.

1 What are teachers’ perceptions of their classroom environments? This question utilizes teachers’

experiences in classrooms as a method of gauging how classroom environments currently work.

2 What is the structure of teaching and learning activities associated with the National Curriculum and the differing uses of the National Curriculum?

3 How is the classroom environment being used during the teaching and learning activities associated with the National Curriculum?

4 How does the organization of resources in the classroom environment support the teaching and learning activities associated with National Curriculum? These three questions examine the physical environment in relation to the spatial implications of the National Curriculum through a series of observational studies.

5 Is it possible to support and improve the design of primary classroom environments to enable a better delivery of the National Curriculum? This question challenges existing approaches to the design of classrooms.

Of the 44 lessons observed in this study, 12 adhered to the standard lesson structure, which ranged in duration from 30 to 70 minutes. Dual activities were observed taking place in 20 lessons, with durations ranging from 30 to 100 minutes, and finally 12 lessons were categorized as multiple activity lessons, that ranged in their duration from 70 to 100 minutes.

In addition to the order in which activities took place, the amount of time noted in each category was recorded by percentage for each lesson, informing the amount of time spent in each category. It was observed that the percentage of time relating to administration varied from 5.0 to 16.7 per cent of the duration of lessons, and periods of introduction ranged from 2.0 to 16.7 per cent. The periods of the lesson devoted to teaching activities took up the most time and ranged from

50.0 to 85.7 per cent of the lessons observed. Periods of transition between teaching activity in dual and multiple activity lessons ranged from 2.4 to 12.0 per cent. Plenary took between 5.5 and

23.0 per cent of the duration of lessons and concluding stages ranged from 2.8 to 16.7 per cent of the total duration of lessons.

In the lesson structure outlined previously the pupils were all involved in similar teaching activities simultaneously. However, field notes revealed that individual pupils moved on to other activities whilst other members of the class concluded their teaching activity. This often took place in the same location but children were sometimes observed moving to other areas of the classroom as illustrated by Figure 5.11, where children finish an activity and go on to collect books from shelves in the corner (Lesson: 03, Classroom: 01, Time: 34 minutes).

The five main types of pupil activity were recorded using the following categories:

1 Engaged on task

2 Task related

3 Distracted

4 Waiting

5 Other.

The data indicates a considerable degree of consistency across most of the lessons observed. Pupils spent on average 85.2 per cent of their time engaged in tasks, with differences in task engagement ranging from 60.0 to 92.1 per cent. This included periods of administration, introduction to activities and the plenary.

The whole class being distracted was never recorded. However, individual pupils were recorded in the field notes as being distracted by something going on in the classroom, as illustrated by Figure 5.12 (Lesson: 31, Classroom: 11, Time: 16 minutes). The classroom was a converted dining hall, which also served as a corridor between two other classrooms and the rest of the school. Here, another class and teacher are observed moving through the classroom to gain access to another part of the school.

Distractions were also caused by something taking place outside the classroom, such as another class walking past the classroom entrance. Other teachers experienced no interruptions during lessons. This was a chance finding but it was clear that it had a marked effect upon the lesson structure and some pupils’ concentration.

|

|

Three main types of teacher activity were recorded using the following categories:

1 Teaching

2 Managing

3 Unrelated.

The data shows that teachers spent on average 81.3 per cent of their time teaching, which in the 44 lessons observed ranged from 66.6 to 93.8 per cent. Time spent managing was very varied ranging from 7.2 to 53.0 per cent, with on average almost one fifth (17.5 per cent) of their time spent managing. A little less (14.8 per cent) was spent on unrelated issues, such as dealing with school administration.

There appeared to be a complex relationship between teaching and managing. The reasons for this included factors such as the teacher wishing to

use his or her time differently with different groups, with some activities requiring the minimum of the teachers’ or learning support staffs’ input. Other reasons included a shortage of equipment required for that particular activity so that only small groups of children could use it at any one time. An important concept here is differentiation. Pupils do not learn at the same rate or in the same way. They need different sorts of instruction, different access to subject matter and varying amounts of practice and reinforcement. Sometimes whole class teaching may provide this, but at other times only differentiating the learning situation in a more radical way can provide this. If an activity requires a substantial teacher input, the teacher must manage his or her time carefully to respond to these needs.

Within the classroom environment learning support staff were observed supporting teaching

|

|

activities, which included consolidating learning, and keeping children engaged in tasks, as well as reading with small groups and individuals. They were also observed supervising practical activities

and resolving minor difficulties, often circulating from one group of pupils to another, as well as working with pupils from the class in another location, such as the school library. Their presence

Figure 5.13

![]()

![]()

![]()

Whole class teaching activity seated at desks (Lesson: 08, Classroom: 03, Time: 10 minutes). (© John Edwards.)

Whole class teaching activity seated at desks (Lesson: 08, Classroom: 03, Time: 10 minutes). (© John Edwards.)

freed the teacher to give more attention to teaching other individuals or groups.

The most common form of class organization recorded was whole class and individual arrangements. Whole class organization was encountered at some point in all 44 lessons ranging from 10 to 100 per cent of the lesson duration. Groups were encountered in only 4 lessons, ranging from 47.0 to 70.9 per cent of the lesson duration, and paired organization in 3 lessons, ranging from 32.3 to 90.0 per cent. Individual organization was noted in 34 of the lessons and varied from 17.0 to 90.0 per cent. The classes were observed leaving the classroom twice. This was for school assembly, however, it was noted by class teachers that the whole class sometimes left the classroom with the teacher to work in another part of the school, such as a computer suite or quiet room.

When the children were observed as a whole class they were undertaking the same activity at the same time, often seated focusing on the teacher at

one end of the classroom, which meant some pupils had to turn their chairs in order to see the teacher, as in Figure 5.13 (Lesson: 10, Classroom: 04, Time: 30 minutes), or they were gathered together in one part of the room, such as a carpeted area of the room, as in Figure 5.14 (Lesson: 42, Classroom: 15, Time: 8 minutes). Pupils often worked in groups with another child or individually after a whole class session, during which the teacher had explained the task or activity to follow.

During the course of lessons pupils were observed working with the teacher or a member of support staff in a particular part of the room, as demonstrated in Figure 5.15 (Lesson: 02, Classroom: 01, Time: 03 minutes). Sometimes they were organized in ability groups for specific lessons, which was most common during literacy and numeracy lessons.

However, although there was a high level of variation observed in class organization, the layout

|

|

of the classrooms did not change significantly and therefore did not reflect the mode of working. Studies of primary classrooms consistently report that primary school pupils spend most of their time working alone. They also show that they get most of their limited direct teaching contact as whole class members, not as individual learners and though teachers spend more of their time with their class as a whole, individual work remains the most common type of activity for children when they are not working with the teacher, amounting to between 17.0 and 90 per cent of a pupil’s classroom time.

Although the data collected did not include the type or duration of interactions the teacher had with the pupils, the field notes taken during the observations revealed that the teacher interacted with the whole class, with groups of pupils and individually with pupils. Working individually with the teacher or learning support staff member was a

relatively rare occurrence. This usually depended on the individual needs of each pupil as well as the type of class organization adopted during teaching activities.

By far the greatest amount of time spent interacting with the teacher was as part of whole class teaching activities. The teacher would interact with the whole class, either by addressing pupils where they sat as Figure 5.13 (Lesson: 10, Classroom: 04, Time: 30 minutes) or by arranging the pupils to sit around the teacher on the floor as illustrated in Figure 5.14 (Lesson: 42, Classroom: 15, Time: 8 minutes).

In all the lessons observed there were variations in the time pupils worked in whole class, and in mixed ability groups with the teacher or member of learning support staff. However, these variations took place within the framework of established routines. It appeared that in most classrooms, each pupil had a regular place, but they often moved

|

|

around the room to be seated in ability groups or to work with learning support staff that were present. Pupils were also observed interacting socially with other pupils during the main teaching activity.

Teachers have a tendency to spend extended periods of time in specific locations within the classroom and certain areas were identified as being used more than others. When teachers were interacting with the whole class, they were observed to be less mobile. When teachers were interacting with individual pupils or small groups their movement around the classroom increased.

When analysing the Classroom Data Sheets it was found that the teacher’s movement around the classroom was very repetitive. However, there was always a preferred route taken by the teacher and usually it was a repeated and predictable route. From this main route the teacher branched out to other locations in the room. No pattern was

found in relation to its location in the classroom layout, but this main route was always present. In summary, the location and movement of the teacher within the classroom does not relate to the layout of the room but to the teaching activity and organization of the class.