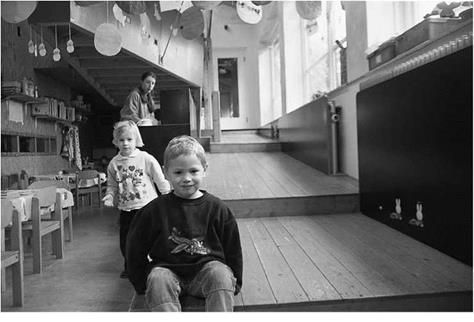

Ten years ago I visited an exciting new children’s daycare centre in Souest, Netherlands. I observed that if children were allowed, they would spend as much time as they could outdoors, in any kind of weather. I noticed that in this particular setting, even when children were not allowed to go outdoors, they still sought to utilize the whole of the interior environment. They would, if permitted, explore linen cupboards, climb stairs (or any type of feature which enabled this to occur), set up games in corners and niche areas, and mount stairs to access high level walkways. All of these features were fundamental to the architectural experience at Souest. This determination to explore is, I surmized, an essential ingredient for learning and healthy social development.

What this design succeeded in doing was to create situations which afforded children a sense of adventure where they could test their mental and physical coordination with a strong illusion of their own independence. I noticed how children were engaged in their own self-generated activities, played out in different corners and areas of their daycare ‘landscape’. I concluded, that for young children in particular, there was no perceptual difference between an exterior landscape and an interior landscape. Indeed, children would relate to both in similar ways if allowed.

Perhaps the key dimension of this was the process of listening and hearing the views of children which had largely dictated the framework of its architectural development. For Venhoeven, the children’s voices were what he needed to hear loudest. Ultimately children’s needs dictated the form of that labyrinthine, multi dimensional environment to create a really child-centred design. This, in my experience, is a rare and inspiring convergence of educational and architectural wisdom.

The architect had deliberately diminished what he considered to be an overpowering health and safety agenda which threatened to stifle imaginative creativity with layers of bureaucracy and restrictions. By and large, most children’s environments, nurseries and schools are predicated around a narrow health and safety agenda limited by cost constraints. New and existing nurseries and childcare centres are generally of a very poor quality compared to most other public buildings. Small buildings with small budgets do not usually allow adequate resources to be devoted to areas such as developing a meaningful strategy for consultation with the end users within the design process. As a consequence, these buildings are often designed to a lowest common denominator. In the worst cases they adopt a quaint adult perception of what children’s architecture should be; this then is ‘bolted onto’ the building as something of an after-thought, perhaps with the use of very explicit childlike references such as teddy bear door handles or decorations which are over elaborate, or perhaps by utilizing strident primary colours which are aesthetically poor. All this does for children is to patronize them and to make them feel as small as they obviously are. Children, young or old, know good design when they see it. They are aware of quality. This is particularly so for the older age ranges where they want to be seen on stylish play equipment.

Elsewhere, beyond the confines of the childcare centre or the school, an urban environment has evolved which offers only moderate benefits to modern childhood. Looking back it seems that little has changed. In The Theory of Loose Parts, Simon Nicholson (1971), son of artist Ben Nicholson and sculptor Barbara Hepworth, wrote an article about the importance of creativity for children

lllust A

The childcare centre at Souest, Netherlands designed by Ton Venhoeven. A challenging ‘landscape’ for early years’ play and learning. The children perform gleefully for my camera, running up and down this stepped ramp, with the adult carer relaxed and impassive. Today health and safety guidance coming from most education authorities in the UK would ban such a potentially hazardous feature. (Photos: Mark Dudek.)

The childcare centre at Souest, Netherlands designed by Ton Venhoeven. A challenging ‘landscape’ for early years’ play and learning. The children perform gleefully for my camera, running up and down this stepped ramp, with the adult carer relaxed and impassive. Today health and safety guidance coming from most education authorities in the UK would ban such a potentially hazardous feature. (Photos: Mark Dudek.)

participating in play schemes. He called his article ‘How NOT to Cheat Children – The Theory of Loose Parts’. In it he made a number of key observations regarding the lack of involvement children have with the design of their spaces. Although published thirty years ago, it remains a cogent reminder of the importance of young people’s participation in the design process, and in

the scope they have to modify or change their spaces subsequently.

One particularly interesting section of his piece is worth repeating here:

In any environment, both the degree of inventiveness and creativity, and the possibility of discovery are directly linked to the number and

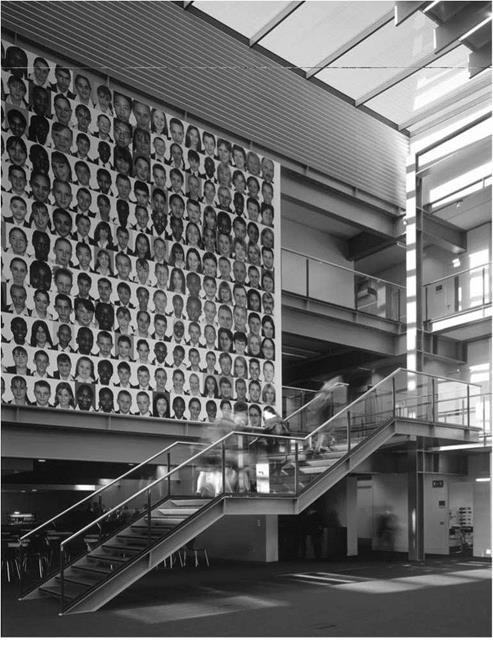

lllust B

(a) The main

(a) The main

entrance atrium has high quality graphics; images of every student personalize the space.

Extended caption

The Bexley Academy, a new secondary school designed by Foster and Partners. It is an environment which treats children with respect. Walk through the doors of Bexley and the interior immediately feels more like a corporate headquarters than a school. From the entrance and reception desk, visitors have views into a large top-lit atrium space and beyond to the restaurants, meeting rooms and classes, many of which take place in open-plan areas. Even traditional closed classrooms are highly glazed to make the activities transparent and visible. Each classroom appears to be filled with flat screen Apple Macs with teachers standing at interactive white boards. These buildings are lavishly appointed particularly in information and communication technology.

lllust B

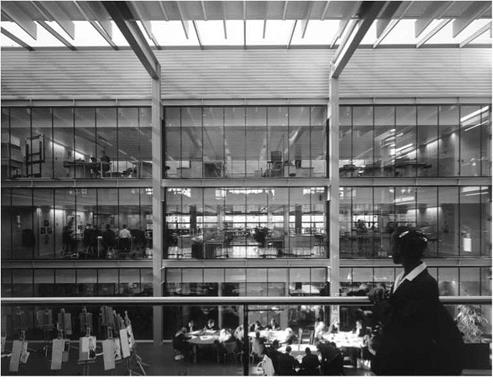

(b) The teaching atrium with an art lesson taking place outside the confines of a traditional classroom.

(b) The teaching atrium with an art lesson taking place outside the confines of a traditional classroom.

Extended caption (contd.)

The scheme is organized around three top-lit, glazed courtyards, each with a different functional theme; there is the entrance business court (designed like a mock trading floor), a technology court and an art court. Users are constantly aware of the whole school community simply because they can see what everyone else is doing. No hiding behind the bicycle sheds here.

According to the lead architect, Spencer de Grey, the scheme sponsors took some lessons from the architect’s own office layout, which consists of open-plan working areas with discrete bays off the main spaces to provide for quieter more contemplative activities. ‘The main emphasis is on transparency to create a different slant on the normal educational experience,’ he says.

That ‘different slant’ is conditioned by the fact that city academies depend on business for an element of their financial support. They receive preferential public funding in return for concentrating on a particular curriculum, so supporting a key plank of the UK government’s education strategy – specialism in vocational subject areas. (All photos by Nigel Young, Foster & Partners.)

kind of variables in it… it does not require much imagination to realize that most environments that do not work (i. e. do not work in terms of human interaction and involvement) such as schools, playgrounds, hospitals, day-care centers, international airports, art galleries and museums, do not do so because they do not meet the ‘loose parts’ requirement; instead, they are clean, static and impossible to play around with. What has happened is that adults in the form of

professional artists, architects, landscape architects, and planners have all the fun playing with their own materials, concepts and planning alternatives, and then builders have had all the fun building environments out of real materials; and thus has all the fun and creativity been stolen; children and adults and the community have been cheated and the educational-cultural system makes sure that they hold the belief that this is right. How many schools have there been with

chain link and black-top playground where there has been a spontaneous revolution by students to dig it up and produce a humane environment instead of a prison.11

His polemical thesis reminds us of the arid scaleless school buildings which many of this generation’s parents grew up in. A lot of these sites are still in use today and in Chapter 5 Ben Koralek and Maurice Mitchell describe how they worked with children and architect students incorporating their joint thinking into a scheme to adapt a number of Victorian Board School spaces to make them fit and inspiring places for modern education. This chapter, which is central to our publication, reminds us of the need to interact with children as much as to instruct them. The best form of architecture for education is the result of an informed dialogue between teachers and children, where children feel that they can have an active involvement in the decisions which shape their lives. The architecture is the third dimension, which creates the whole.

My aim with this book therefore is to stimulate more debate about education and its context, buildings and processes which take place there through the views of children. The contributors are drawn from a range of disciplines which are not specifically architectural. As a consequence, language and general terms of reference are not always consistent with the overall architectural theme. However, through this inter-disciplinary approach, I hope to encourage better understanding of key issues which contribute towards the landscapes of childhood. What I am clear about is that the current education dictates, upon which many school buildings and dedicated children’s landscapes are predicated, are not fit for the twenty-first century.

Each one of our contributors has been asked to consider the evolving nature of children’s culture and the environments within which it is currently being played out. Children spend a great deal of their waking lives in daycare facilities and at school, as parents are often engrossed in wall-to-wall work. This places an emphasis for architects and planners to consider the needs of children in a new light. Arguably, the children’s environment must be conceived of as a ‘world within a world’; it should be a special place with all the aspects that make the environment a rich landscape for exploration and play. And this ideal should apply well beyond the nursery.

In the childcare centre he designed in Souest, architect Ton Venhoeven had deliberately incorporated ramps, terraces and level changes which encouraged children to climb and explore, just as they would in a natural landscape; indeed Venhoeven explained that his inspiration for that interior had been his own childhood play area, a wild rambling garden around his house which had a large wooden boat marooned there, a long-term restoration project for his father. As a child, Ton played in it, around it, and underneath it.

Although the boat never actually made it back to the water, it fulfilled a crucial childhood fantasy. When he was subsequently commissioned to design a new daycare centre within an existing building, the architect drew on some of his boyhood experiences. He designed a boat form as a recognizable part of the children’s play area at Souest, to create a more dramatic space for children to explore. This transfer of his childhood experience had created a rich ‘interior landscape’, establishing what child psychologist Harry Heft called affordances, the possibility for children to test and develop their physical and social skills through the specific architectural features on offer.12

Venhoeven’s initial inspiration developed into a whole host of affordances, which tested health and safety requirements to the limit. Because of that, the landscape was extremely rich and challenging, not just for children but also for the teachers and carers who used the new building. It has, over the years, become a positive benefit to everyone involved, in particular for the children who attended during their formative years. It is an environment which trusts children.

It is my strongly held view that most children do not really differentiate between the interior and the exterior of a building. To most, the landscape is simply there to be explored in its own terms, as and when it is available to them. The freer they are of adult supervision and the richer the landscape for exploration, the more benefit that environment will have for them in developmental terms (until a painful fall adjusts their adventurous spirit). That is why the digital environment of the internet holds such attractions for older children. It is relatively free of adult control and supervision.

The best landscapes enhance development for all children. The best form of learning takes place within an integrated environment of architecture, technology and teaching, which comes together seamlessly. If it engages the child, it will enhance their learning and their social development in equal measure. The landscapes of childhood are everywhere, however, today they are no longer freely available to children. As a result the real needs of children for freedom and adventure in their own worlds are censored. We must somehow give this back to them.

Mark Dudek, June 2004

Notes

1 The Pocket Oxford Dictionary describes a child as ‘a young human being’. Our definition of a child covers the age range 0-16, recognizing the reliance most teenagers have to their parents, even when the relationship they have may be poor.

2 Stranger Danger Drive Harms Kids, the Observer, 24 May 2004.

3 Daycare is a full-time care and education which enables parents to attend full-time work during the child’s early years. It provides structured play which is intended to support the child in its own personal development and unlike parttime sessional nursery or creche, it requires a purpose-made environment rich in stimulation and sensory pleasures.

4 Private Eye Magazine, London, no. 1105, 30 April, p. 14.

5 A Life in Secondary Teaching: Finding Time for Learning, commissioned by the National Union of Teachers from independent researchers John MacBeath and Maurice Galton, Cambridge University Faculty of Education.

6 ibid, p. 3

7 Schools for the Future, Department for Education and Skills, 2004.

8 Aldrich R. (1998). The National Curriculum: an historical perspective. In (D. Lawton and C. Chitty eds) The National Curriculum, Institute of Education, London.

9 ibid, p. 8

10 From OECD Forum on Schooling for Tomorrow, Futuroscope, Poitiers, France, 12-14 February 2003, Document No 07. The report provides information note for Netherlands for the Forum session on Building an Operational Toolbox for Innovation, Forward Thinking and School System Change.

11 ‘How NOT to Cheat on Children – The Theory of Loose Parts’ by Simon Nicholson published in Landscape Architecture, October 1971, pp. 30-34.

12 For example, Heft cites a smooth flat surface,

which affords or encourages walking and running while a soft spongy surface affords lying down and relaxing. Heft, H. (1988) ‘Affordances of children’s environments: a functional

approach to environmental description’, Children’s environment quarterly, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 29-37.

Mark Dudek has two children. He lives and works in London. He has written and broadcast on many aspects of school and pre-school architecture. The second edition of Kindergarten Architecture was published in September 2000 (SPON). Other recent publications include Building for Young Children published by the National Early Years Network and Architecture of Schools – The New Learning Environments published by the Architectural Press in 2001.

He has also been involved in the design of numerous educational facilities. With his architectural practice Mark Dudek Associates, he recently completed the Windham Early Years Excellence Centre in Richmond upon Thames, UK. He is currently working on a range of education projects including new buildings for the National Day Nurseries Association in Grantham and Birmingham, UK. He has designed and supervised the construction of one of the Government pilot projects ‘Classrooms of the Future’ at Yewlands Secondary School in Sheffield and is working on a new ‘eco nursery’ for a rural community in South West Ireland.

The editor has lectured all over the world including a recent series of AIA talks in Michigan, USA. He has been a keynote speaker at many conferences organized by groups such as Surestart, The Daycare Trust, the National Early Years Network, National Day Nurseries Association, The

Regional Childcare Working Group, South West Ireland, NIPPA (promoting quality care in Northern Ireland) and CABE (the UK Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment). He presented a paper at the conference ‘Exploring the Material Culture of Childhood’ at the University of California, Berkeley in May 2003 and was a keynote speaker at the conference ‘Spaces and Places’ for children organized by Canterbury Christ Church University College in 2004. He is a Research Fellow at the University of Sheffield and a CABE Enabler.