The first consideration must be that of meeting or exceeding the minimum statutory requirements relating to the provision of play space, first in regard to safety and suitability but then in relation to accessibility and the inclusion of all. The second is to consult potential users and their communities. Here it needs to be borne in mind that children, when consulted, can adopt a realistic and shrewd approach to expressing needs, but are as liable to be readily persuaded as their parents to adopt either the latest trend or an entirely traditional approach to play space. Sometimes both groups may, for understandable reasons, fail to take into account wider community interests and priorities.

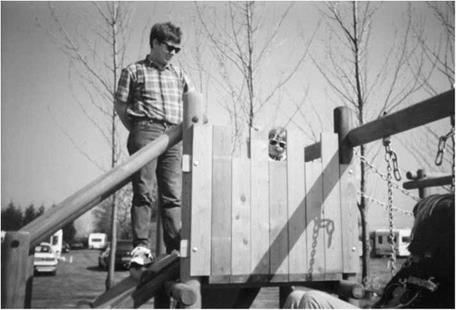

Playgrounds tend to serve particular groups and communities and seldom, except in holiday resorts, camping and caravan sites and commercial premises, attract significant numbers of children that are not local and commonly acquainted, if not friends and neighbours. The strategic planning for a new or improved playground must, therefore, take account of and respond to long-term local community needs. These include the current and projected age structure of the immediate locality

and the proximity of the proposed site to children’s homes and schools. This is of increasing importance in catering for the play needs of disabled or otherwise disadvantaged children, their parents or other carers. Land cost is a significant consideration, including alternative site usage and development potential, especially possible benefits from ‘planning gain’. Local housing trends, new estates under construction and areas subject to clearance, upgrading or redevelopment need to be taken into account. Specific consideration should be given to residents who might object to a playground, the elderly or the sick, perhaps, for whom noise would be an unwelcome intrusion. On the other hand, isolated sites are rarely appropriate: for children to be discreetly

overlooked is to be safe.

Other considerations are:

• Safe, well-lit access via paths, cycle tracks and roads.

• Opportunities for shared and mutually supportive roles such as neighbouring council park nurseries providing experience of growing and propagation.

• Any environmental or other hazards, i. e. standing water, railway lines, electricity substations and pylons, busy roads and previous, possibly contaminating, land use.

It is worth bearing in mind that, even in small and isolated communities, the range of purposeful activities can be extended through cooperation and liaison with schools and local authorities. Play equipment and facilities can be purchased and maintained on a shared basis while there are attractive opportunities for extending play through a mobile play unit on the lines of the mobile library. This procedure is specifically commended and endorsed in Getting Serious about Play.10

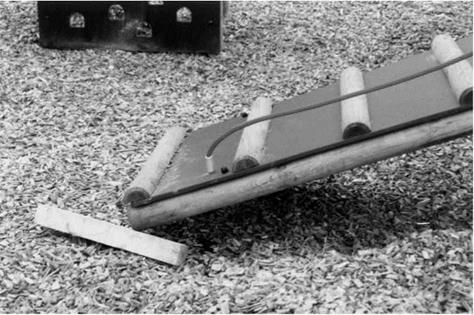

Whatever the immediate local priorities, there is always a limited budget to work within and some essentials of design remain valid, regardless of fashion or finance. Natural features such as a sloping site can add to amenity use at no cost in, for example, providing a ready-made slope for a mound slide or a BMX track. Similarly, inherent

|

|

|

|

|

|

physical features can assist in ensuring a clear separation of age-related play apparatus and amenities. The early stages of planning should always take into account the very different play needs, interests and physical capabilities of children at various ages and stages of their development. The age – and ability-based zoning of play equipment is an important issue. As an aid to supervision, high visual barriers, including trees, limiting long sight lines to all parts of the play area should be avoided. Such boundaries as low-level hedging, can, however, divide an otherwise bleak space in an imaginative way, creating small enclosures and giving children a sense of privacy without limiting opportunities for adults to oversee activities from a distance.

It is worthwhile spending a great deal of time at the planning stage since good playground design aids the development of social, creative and intellectual interaction between children, as much as physical activity, and allows younger, less robust and more timid children to share as much from observation as from active participation in play. Provision for social space, including well-planned arrangements for seating and shelter, encourages parents and other carers to stay on site, and can

constitute an important safety feature as well as helping to guard against bullying and vandalism.

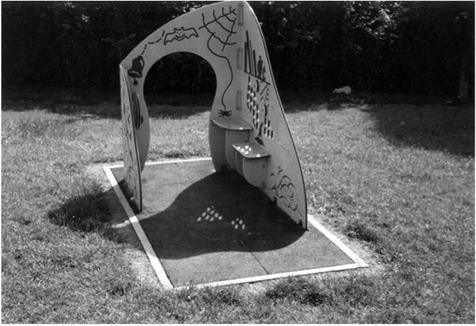

As we have argued previously, every opportunity should be created for extending the concept of the playground to meet a wide range of developmental needs. This is not merely a place for exercise and amusement, but a space where every opportunity should be taken to encourage creative, exploratory learning experiences. Low cost, renewable and inclusive access to play can be developed by, for example, regarding paved areas and paths as potential mazes, hopscotch pitches, giant snakes and ladders boards and painted target areas. Sundials can be created with painted panels, designed to use children as the gnomon; this could form an entertaining, educational and entirely practical self-help community project. Surfaces prepared for use as ‘graffiti boards’ encourage artistic expression and perhaps focus genuine graffiti in specific, readily-cleaned locations. If the whole community is to be involved, then a ‘trim track’ set up with regularly updated age-related targets and achievements would be called for.

Part of a growing problem in approaching the design of play areas derives from the mistaken belief in a community-inspired need to temper boldness

in concept to the mundane requirements of conventional play areas; whereas what is in fact needed is age – and ability-related, as well as accessible, play provision that also has elements of excitement and surprise for all users. The importance of drawing upon the natural environment cannot be overstated. The priority here is play mounds rather than landscaping, wild flower meadows as well as areas of close-cut grass and living willow structures designed as tunnels, arches and gathering places. Weatherproof signs and screens illustrating commonly observed local wildlife encourage learning and observation, while the display of ‘archive’ pictures showing the park/playground in former times might encourage a sense of community ownership and history. Whatever is decided in relation to layout, the emphasis must be on function rather than appearance.