Catherine Burke

One of my earliest memories of school is associated with fear of the school dinner hall. One day, during the school meal, I felt sick and discovered an escape route from the daily hazard of dinner time. I was allowed to lie down on a camp bed inside the reception class room and was left. I found great comfort there with no one to worry me. Somehow I managed to escape each dinner time for a few days as I found myself experiencing the same symptoms as soon as midday approached. A sympathetic teacher led me once more to the little camp bed and I was left alone. Like so many children, it was perhaps the fear of losing control and becoming ill which caused the anxiety and actual symptoms. This may have been magnified by the strange regimentation of large numbers eating together according to rules and orders set down in what was to me, as a newcomer in the autumn of 1962, the alien environment of the English primary school.

The school meal at that time, when the school kitchen was far from universal, was often delivered each day in large lorries, the hot food contained in metal vats. It smelled and tasted like no other food consumed anywhere and nothing about it was fresh or newly harvested. Growing up in an urban environment in Britain during the 1960s, children were far removed from horticulture and were accustomed to highly processed foods which were pouring on to the newly fashionable supermarket shelves. Few of our mothers preserved their own jams and marmalades. Tinned peas and carrots and packaged powdered potatoes, as well as factory – produced white sliced bread were our every day reality. The school meal merely magnified this reality further. Food, or its absence, structured our days and accompanied our play. We skipped to rhymes about food, we chanted in the playground, creatively playing with the sounds of the contents of school dinners. Salad became ‘rabbit food’, macaroni became ‘drainpipes’ and currant cakes ‘dead flies cemetery’. Stew was ‘spew’ and we ‘washed it all down with a bucket of sick’.

Iona and Peter Opie trailed the country during the 1950s and published their famous book The Lore and Language of School Children, in which they documented the cultural landscape of school children at play. In it they noted:

The possessors of young and healthy appetites are lyrical about their food. School dinners are ‘muck’, ‘pig swill’, ‘poison’, ‘slops’, ‘S. O.S.’ (Same Old Slush), and ‘Y. M.CA. (Yesterday’s Muck Cooked Again’).*

Once a week we carried with us to school our packed breakfasts. This was to allow us to take Holy Communion at the school mass, sometimes held in our classrooms. As Catholic school children, we were not permitted to eat or drink anything for twelve hours before the school mass. Cold buttered toast consumed with friends in the classroom on a totally empty stomach tasted heavenly. I noticed for the first time, through the contents of these breakfasts, that my classmates

|

Figure 12.1 Serving the school dinner: 1950. |

came from homes and backgrounds which differed from my own as revealed in the strange and fascinating toppings and fillings of their sandwiches. School gardens, where they existed, were tended by the school caretaker and contained rocks and flowers. We were to keep away from them. Occasionally children would get into trouble for picking the flowers. The idea that children should learn to garden was out of fashion in an ‘enlightened’ era that was striving to embrace the educational challenge of ‘the white heat of technology.’2

Today, as my children attend school, the school meal and its environment has taken a different shape after two decades of deregulation and privatization. At one time the school kitchens and dining spaces were regarded as symbols of modernization and progress. Now, the space most usually associated with progress and quality is the ubiquitous computer lab. Technologies servicing large-scale food preparation and consumption are seemingly of less importance than technologies serving up web pages from around the world. At the same time the preparation of food has been ‘raised’ to the status of a technology itself through a re-branding exercise. As specified by the UK National Curriculum, children and young people no longer merely learn to cook; they practise ‘food technology’.3 Food consumed in school, whether purchased in the canteen or tuck shop, or whether brought to school as a packed lunch is generally highly processed, resembling little of its original source. Drink consumed is likely to be canned and branded. In some quarters, as children become physically less active and nutritionally more wanting, concerns are being voiced about the health consequences of heavy reliance on processed foods in their diets. The ‘McDonaldization of diet’ is a shorthand for rising levels of obesity and associated disease in school – aged children and the spread across Europe of American-style eating habits.4

Children and young people today are widely considered to be out of touch with the origins of the food they consume and have little awareness of the nutritional value of what they eat. The parent or grandparent who traditionally passed on essential wisdom about food and survival can no longer be taken as given in many families. The industrialization and commodification of food has supplanted the family as a site of learning and the food industry has profited massively from the expectation that women will structure their lives around the workplace rather than the kitchen. However, it has been recognized since the inception of mass schooling that school was a means of equipping those out of touch with such wisdom with the tools of survival. During the second half of the twentieth century, however, the association of manual work with low paid occupations encouraged the mainstream educational establishment in Europe and the United States to place more value on academic knowledge and competencies. This continues today as literacy, numeracy and the development of skills in Information and Communication Technologies are compulsory subjects in schools. Gardening, once an established part of the curriculum, is sidelined as an after school activity if it exists at all and cooking would have disappeared entirely from the curriculum were it not re-branded as a ‘technology’.5

But there are exceptions. Schools outside the mainstream, such as Steiner or Waldorf schools, have maintained work with the hands as of equal value to work with the mind. This is not usually the case in mainstream schooling. However, a renewed appreciation of the edible landscape of school is currently generating cutting edge projects advancing curriculum design and architectural planning within schools. Some of these examples will be explored in this chapter. The ‘edible schoolyard’, part of an international ‘growing schools’ movement is evidence of a reassertion of the maxim, ‘We Learn by Doing’. Initiatives such as these have the potential for changing schools and the experience of learning just as much as e-learning projects which attract so much attention and sponsorship. The evidence presented in this chapter argues the case that for children, the edible landscape matters just as much as the electronic landscape which they embrace. Food is fundamental and despite official and professional preoccupation with pedagogy that embraces the revolutionary potential of computer-supported learning and teaching, for children and young people the edible landscape represents an essential part of survival in the modern school.

It has long been regarded as essential that children should learn how to prepare and produce food for the domestic table. For most of the twentieth century, this was a prescribed activity for girls. It was considered to be so important – indeed for many the principal reason for allowing girls to be educated at all – that often a flat or apartment was attached to the school where older girls could practice their ‘house craft’ skills in a realistic setting. Girls educated in the 1950s and 1960s may well remember the task of making their cookery overall during several weeks of instruction before commencing cookery lessons. Today, the homely pinafore is rarely seen and pupils are more likely to be clad in industrial apparel such as a white overall and hat. These are significant contextual changes which reflect a fundamental shift in the perceived purpose of education about food. There has developed over recent years a change of focus from the domestic table to the commercial outlet. Indeed, the contemporary emphasis on learning about the technology of food production, particularly in commercial or market contexts constitutes a form of ‘Industrial Pedagogy’ which carries with it serious implications in terms of the quality of education and feeds straight into the hands of the ‘fast food’ giants.

The site for cooking (or food processing) has transferred: from the home and the school; to the factory and catering outlets – and it is this transfer which the national curriculum aims to facilitate and encourage.6

Accordingly, children in the UK spend time designing marketing formats and considering mass production within a technological and industrial approach to knowledge and learning that leaves out much of value in the human understanding of food and its production and consumption. Thirteen – and fourteen-year-old boys and girls in state schools now learn bread making together but they are instructed to conceive of this activity in terms of producing an industrial and commercial product. A worksheet entitled ‘Control Systems for Bread Making’ advises ‘When you make a loaf of bread, you need to check that you have made it properly’.7 One might have in previous generations carried out such a check by simply eating and enjoying the newly baked bread. However, the pupil today is conceived of as the future manager of a production line and the instruction is in keeping with this projection. The pupils are required to behave in the context of ‘a factory system for controlling the bread making process to make sure that the end product is safe and reaches their quality standards’.7 None of the test procedures involve eating or even tasting the bread.

This shift in the culture of food production and consumption in educational environments mirrors the de-domestication of food in the industrialized world. As the processed foodstuffs market continues to expand according to demand for ever-faster, convenient and cheaper foods, these products increasingly dominate the dietaries of households. The Commission of the European Union recently published Nutrition Education in Schools: Europe Against Cancer in which

Schools’ initiative, designed among other things to challenge the knowledge gap that has arisen among recent generations of children and young people between what they eat and the origins of food. A primary outcome of this initiative is the envisaged spread of school gardening projects as an integrated part of the curriculum.9 A separate ongoing project is ‘The Schools Organic Network’, an initiative of the Henry Doubleday Research Association which distributes free organic vegetable seeds in the spring to schools with an interest in food gardening. A website promotes activity through publicizing the achievements of the network of schools.10

Schools’ initiative, designed among other things to challenge the knowledge gap that has arisen among recent generations of children and young people between what they eat and the origins of food. A primary outcome of this initiative is the envisaged spread of school gardening projects as an integrated part of the curriculum.9 A separate ongoing project is ‘The Schools Organic Network’, an initiative of the Henry Doubleday Research Association which distributes free organic vegetable seeds in the spring to schools with an interest in food gardening. A website promotes activity through publicizing the achievements of the network of schools.10

These projects are radical initiatives that challenge many contemporary ways of seeing children and manual labour. The labouring child is an image associated in the modern mind with exploitation, oppression, the antipathy of freedom to learn. This was not always the case. The early Kindergarten movement, especially that part influenced by Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852), recognized in gardening the possibilities for young

Figure 12.3

Children’s Garden, unidentified kindergarten, Los Angeles, c.1900.

children of working with the fundamental structures of life. As a platform for learning, the garden environment, especially if landscaped in a style that mirrored fundamental life forms, would take on the role of teacher.

children of working with the fundamental structures of life. As a platform for learning, the garden environment, especially if landscaped in a style that mirrored fundamental life forms, would take on the role of teacher.

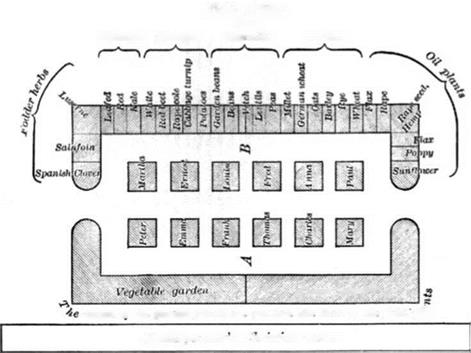

Foebel designed his own children’s garden, which shows the integration of flowers, herbs and vegetables and the individual and communal plots he regarded as fundamental for the spiritual and social development of young children.11

For many in the United States, working the land is associated in popular memory with images of slavery. On both sides of the Atlantic, farming is associated with a precarious lifestyle and rarely with good standards of living. Images of child labour and child slavery are generally employed to argue the case for universal schooling as an essential feature of ‘development’. In Britain, images of the labouring child are read in conjunction with a progressive view of educational history which sees the gradual emergence of an academic education as an entitlement for all children. Already, in the early twentieth century, the relative demotion of gardening in the school curriculum was apparent when teachers were forced to argue its case. But

the benefits of cross-curricular integration were fully appreciated by commentators. ‘Gardening as a school subject… should not be regarded as a training for industry, but should lead to an interest in nature. It should not be treated as an isolated subject, but every opportunity should be taken to use it to add reality to the ordinary work, and the ordinary work should assist the gardening’.12

For a short period, during the war years, schools in England developed garden plots to help supply the food for the midday meal. In November 1941, one school noted in its log book: ‘Dinner cooked in the school – meat and four vegetables, pudding and custard – costs 3d. per day. All vegetables except potatoes from the school garden’.13

The selective system of secondary education which was adopted by the majority of Local Education Authorities in England following the 1944 Education Act helped to further undermine gardening, horticulture and animal husbandry. Those children, tested at eleven years, who were considered academic, would be protected from getting their hands dirty in the grammar school environment where they would be nurtured towards a professional career. Children considered

![]() Figure 12.4

Figure 12.4

‘The Garden for the Children is the Kindergarten’ from Friedrich Froebel’s Education by Development, New York, 1899.

УІіигег garden

name[11] of the garden jitunt» arr put Iterr till – thorn of the fiehl pt*

|

|

less bright would be channelled to schools where manual work on the land, particularly for boys, was a necessary part of the curriculum. The relegation of garden work and its association within the educational context with lower levels of intelligence has continued until today and has contributed to the negative or demeaning association of horticulture and husbandry with learning.

So how do children and young people themselves view the edible landscape of school? How has this changed over time? How important to them is food and drink in everyday life in school and what does the association with certain kinds of foods signify in the culturally diverse environments of schools today? What is the nature of the forces acting on children within the edible landscape of school, shaping their bodies and minds as they develop their tastes, knowledge, value systems and market power as young citizens? How do they respond to initiatives to integrate the growing and preparation of food into the curriculum?

What follows is an exploration of the edible landscape of school from the points of view of various contemporary players. These are: •

• Teachers and others who are working towards the integration of the edible landscape within the curriculum of school.

• Food companies who are seeking to expand their marketing activities via corporate sponsorship within schools.

An historical perspective or long view of the edible landscape of school is taken to explore and reveal continuities and patterns of change over time. But to begin with, we look at this landscape through the eyes of the child or young person captured at two different points of time in the UK.