President John Christakos puts it simply: “The three things we’re about are elegant design, simplicity of manufacturing, and affordability. We’re trying to take the elitism out of design.”

President John Christakos puts it simply: “The three things we’re about are elegant design, simplicity of manufacturing, and affordability. We’re trying to take the elitism out of design.”

With these fundamental principles in mind, Christakos and his partners Maurice Blanks and Charlie Lazor at Blu Dot set themselves the seemingly straightforward task of making a lounge chair that was comfortable. “Comfort was the main goal; a must, the genesis, and what everything we did hinged upon,” says Christakos. Comfort in a chair is usually associated with upholstery. But part of Blu Dot’s mission is to use mass manufacturing to make things affordable, and upholstery is “a craft, not an automated process,” according to Christakos. They also considered plastic but found the cost of injection molds prohibitive. “So we narrowed in on plywood. It was something we could afford to work in, the molds are relatively inexpensive, and we hoped that the curvilinear shapes that we could get would yield something comfortable. Plus, we’d never worked with it before and wanted to experiment.”

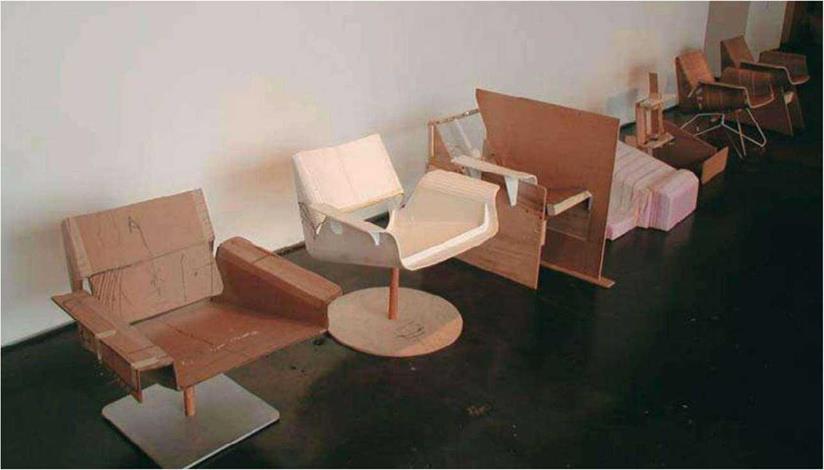

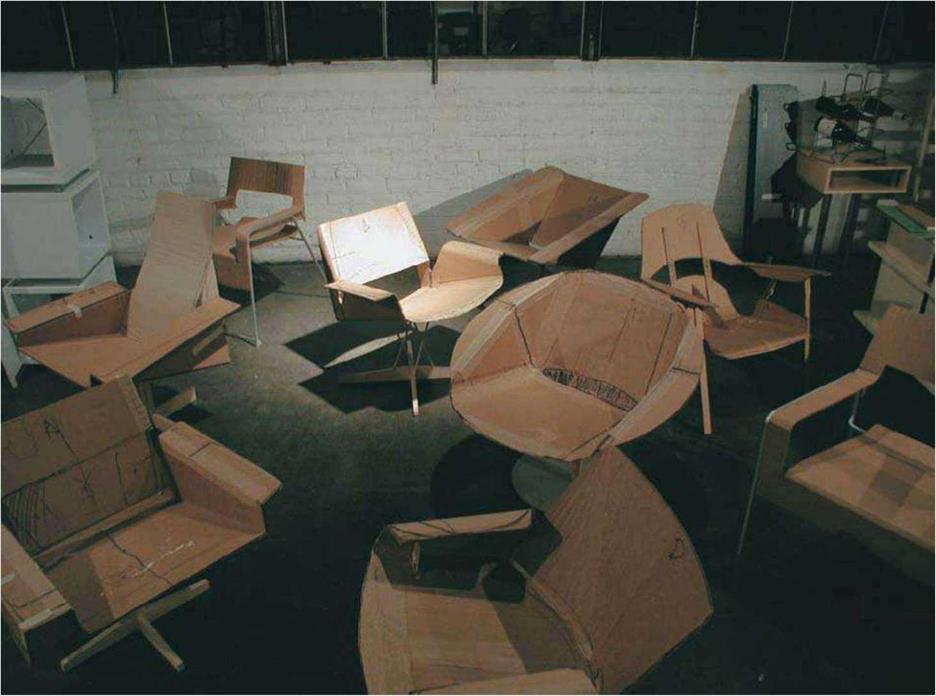

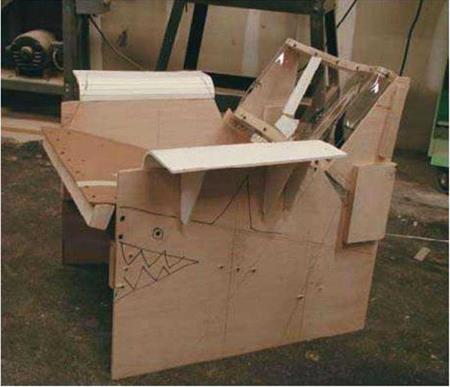

The first part of the experiment was to create sketches and cardboard models. “At that stage, we were just looking at forms,” Christakos points out. “Most of our previous pieces were rectilinear, and it was nice to get back to something more formal, more sculptural.” As they began to focus on a few shapes, they built more refined cardboard models, then went to foam core models, and finally made preliminary molds in their own shop. They shaped pieces of the rigid, pink insulation foam that’s readily available at any building supply store, laid a stack of veneers with glue in between them over the molds, then stuck the whole contrivance into a vacuum bag and sucked the air out of it, forcing the veneers down over the mold and clamping them there until the glue dried and the veneers took on the shape of the mold.

In between the cardboard models and pink foam prototype, Blu Dot spent a lot of time tweaking the shape to maximize the chair’s comfort. They used a seating buck, described by Christakos as “a crude contraption to play around with angles and curves, height, pitch, angle of the back relative to the seat, the curvature of the back, the height of the arms, the position of the arms, etcetera.”

Top: Blu Dot uses the straightforward tools of cardboard, tape, and a big black marker to turn rough ideas and conceptual thoughts into something that’s starting to look like a chair. Credit: Blu Dot

® A seating buck helps designers determine the angles and proportions of a chair’s back, seat, and arms to ensure the final product will be comfortable for a range of body types, sizes, and shapes.

Credit: Blu Dot

® Standard building insulation provides an inexpensive, easily accessible, simple-to-shape material that Blu Dot uses to create an initial mold. Shrink-wrapping sheets of veneer to the form provides the first round of prototypes. Credit: Blu Dot

But they also utilized the basic sit test, getting a dozen or so people in sizes from petite to well over 6’ (1.8 m) tall to take a seat and comment on how it felt. “I discovered that the section between my shoulder and elbow must be short because I always wanted the arms to be higher,” Christakos quips.

“Of two shells we worked with, we discovered in prototyping that one was not possible to make,” he continues. “Plywood can only bend in on one axis at one time, like a piece of paper. One of the designs had this condition embedded in it, and we didn’t discover this until we started prototyping. In order to fix it, we would have killed the form.” So they focused on what would become the Buttercup.

The next step was to find out how to make the back and the seat work together. Christakos explains: “We trimmed the pieces we’d made by hand and then began to play with the connection between the two parts—the seat, which includes the arms, and the back. We ended up with a joint between the two pieces that is not decorative, but functional. The shape is such that if the glue failed, the joint would hold it in place. We used the geometry of the joint to take some of the pressure off the glue and create a shape that is almost self-supporting. We ended up with something that looks like one continuous ribbon of bent plywood.”

The final development step was to create a base. After exploring several options, “we came to the conclusion that the base needed to sit in the background as much as possible,” says Christakos. “We wanted to put this beautiful form on a pedestal. The chair feels like the petals of a flower, so we focused on creating something that’s like a stem.” The base also swivels, which Christakos points out is an especially nice feature for enhancing conversation.

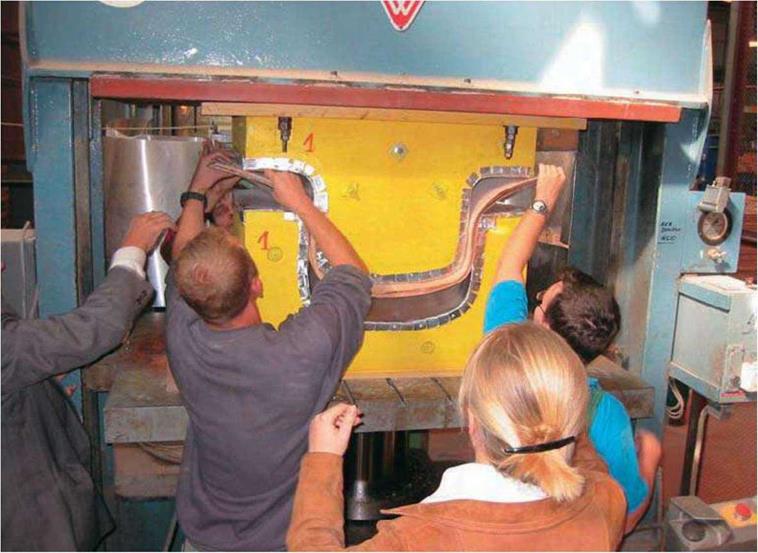

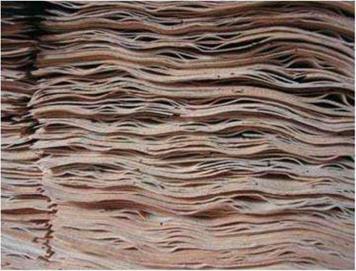

After prototyping, Blu Dot does its own production modeling and drawings and then sends everything to a factory for real production. The Buttercup is manufactured in Poland, and production models feature a decorative face veneer over a core of birch. The veneer is rift sawn, which Christakos says produces a very straight grain that helps accentuate the form.

Christakos found that even though their goal was comfort, they were still surprised by the results. “We never expected it to be that comfortable. The geometry, the opening, and the dramatic curve in the back, all let you just slip right in, and then the chair just grabs you.”

Christakos feels that working as a collaborative practice makes the final design much stronger and more refined. “Nothing comes straight from my sketchbook to the real world,” he says. “Individually, we’ll each spend time sketching or making models or some other representation of our ideas and then we’ll get together, pin things up, share what we like and don’t like, and why. Normally, a few clear ideas start to emerge, and we’ll take it from there to the next level of detail. It’s like sanding, going from 60 grit, to 80 grit, to 120 grit.”

And being actively involved along the entire continuum of initial inspiration to actually selling furniture pieces confers other benefits that end up improving the end product as well. “Because we produce most of the things we design, we live with the practical realities of making, distributing, and servicing products,” Christakos says. “We’re engaged with the more pragmatic concerns like, will we be able to ship it, is it useful, does it solve a problem, will a customer know how to use it, is it produceable in a repetitive way with low defects? These concerns are baked into our process from the beginning. Often, the end form is like the residue of the process, and the product is what’s left over after being driven by just plain problem solving. The form becomes inevitable, as opposed to subjective.”

|

(fy Layers of veneer are glued together and then slid into the mold that will giave them their signature curvature. Credit: Blu Dot

|

^^The sensuous curves of the Buttercup Chair are designed primarily for comfort. The pedestal was designed to be reminiscent of a flower stem. Credit: Blu Dot