He continues, laughing, “Then, I would bring these drawings to friends, and look sad until they gave me money to make prototypes.” This unusual approach to product development goes a long way towards explaining why almost all of his products carry personal names: each has been given the moniker of whoever helped fund their realization.

He continues, laughing, “Then, I would bring these drawings to friends, and look sad until they gave me money to make prototypes.” This unusual approach to product development goes a long way towards explaining why almost all of his products carry personal names: each has been given the moniker of whoever helped fund their realization.

Trained as an architect with a heavy emphasis on engineering and structural optimization, Tayar describes his design approach as a “. . . playful investigation of the relationship between design and mechanical reproduction. Structural behavior is the other guiding component of my design work. I investigate structures with optimal ratios between load-bearing capacity and weight. I try to reconcile the often contradictory requirements of production processes with diagrams of the flow of forces.” Tayar found working with furniture provided him an opportunity to play with —and then solve—various small-scale structural principles.

He recalls, “As I grew older, I started doing more work and having a real office, and sometimes I would get a commission where furniture was required, but often, I would think of a system that was interesting to me, and I would just have it made.” Such was the case with the Calder’s Table.

“It’s inspired by the Barcelona Table of Mies van der Rohe,” Tayar explains. This iconic design features a piece of glass resting on central, crossed metal supports. “The Calder table is almost an explosion of that table base, so instead of having this cross that turns into four legs, just imagine dismembering this space and putting it on four sides of the table,” he continues.

Tayar always consults with a friend who is a structural engineer on projects like Calder’s Table. “Sometimes, we do a full, structural analysis on the piece, or we discuss in concept if this thing might work. I have come up with things that will not work,” Tayar reports. “But with this one, he said, I can’t engineer it, but I think it will work. So we had to just make the piece. Short of making it, there was no real way to try it out.” At the same time, another friend had a connection to a bronze manufacturing facility in Nepal. The support pieces that are the heart of the Calder Table were hand made in a sand casting in Kathmandu.

|

|

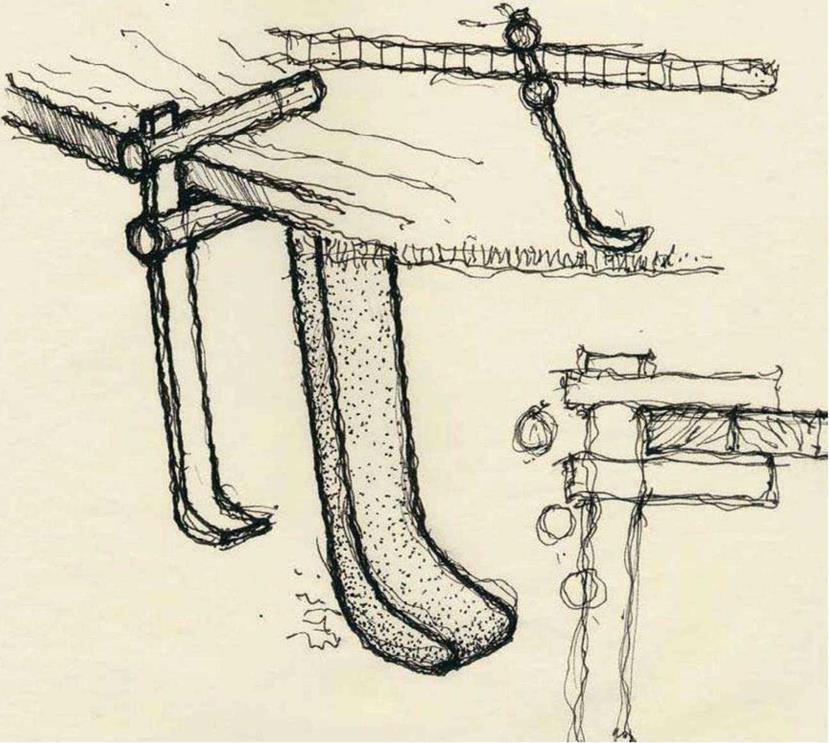

An early sketch outlines the shape of the Calder leg supports; however, the only way to find out if they’d

work was to go ahead and make them. There is a critical trick to how the Calder table functions, as there

credit: ah Tayar are no mechanical connections between the table and the legs.

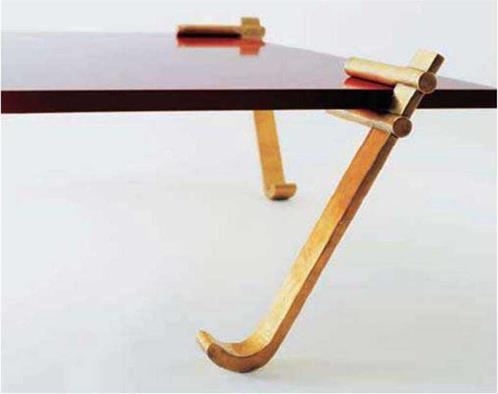

Tayar explains how it works: “The structural design is based entirely on gravity—there are no moving parts. The two rods are offset against each other. Essentially, two people have to hold the piece of wood and then slide the bracket in, vertically. As it rotates, it locks itself in one position. Depending on the thickness of the wood, there is always one, and only one, angle at which the bracket will rest. Once there are three legs, the thing is stable.”

Describing the process of development, Tayar continues, “I would be lying if I said that there was just this one moment when it all came together.”

Named after the son of the photographer who documents all his designs, Tayar says, “. . . at the same time, I enjoyed the fact that the piece evokes the other Calder’s work.” However, the weight of each support gives it a marked difference from the famous artist’s mobiles. “Each piece is so heavy,” Tayar notes. “They weigh 25 pounds (11 kg). They don’t need to be heavy, but the fact that they are does help. Each one wants to fall down to the ground. The top prevents it from rotating, and as a result, it’s kept at a distance from the floor. And, the curved leg always gives the impression of lying at the correct angle. Even if you used a thicker table top, you can’t tell that the geometry has changed. The way

|

the leg touches the floor appears to be properly designed, even though a thicker piece of wood would change the angle.”

When not doing their job creating a table, the bronze pieces still seem to contain some kind of embodied energy. “I generally don’t like finding and reusing objects,” Tayar says. “But the aesthetic of this piece is kind of like a found industrial object. Even alone, the brackets look like they must do something.”

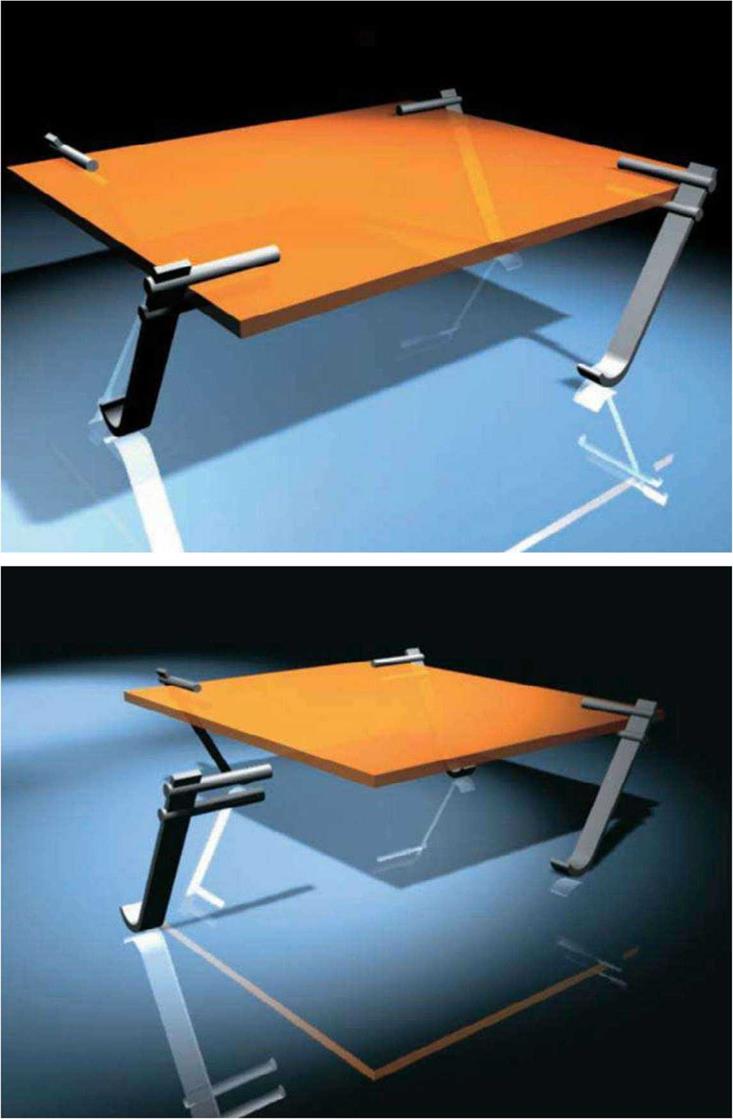

Tayar also takes great pleasure in the contradictions inherent in the particular production processes unique to Calder’s table. “In general, my work is half inspired by structural principles and the other half by production processes,” he reports. “I like very advanced processes, geared towards industrial production. But in this case, I had access to something that represents the first industrial revolution. It’s interesting, in that we would develop 3D models and email the file halfway around the world to someone I’d never seen, they would read it, they’d take these virtual models and create some kind of a mold, cast them, and then FedEx them back to me. The connections were twenty-first century, even though it was reaching back in time to a production process that’s been around for thousands of years.”

In keeping with this international approach, the few Calder tables that have been made have found homes all over the globe. One lives in Capetown, South Africa, another in Beirut, Lebanon, while two have settled in New York City, in the TriBeca and Meat Market neighborhoods.

Now that Tayar has been established in a real office for some time, he finds himself working on a wide range of architecture, furniture, and product designs. “I’ve been doing restaurants, lofts, and homes,” he says, “and these projects are big, so this furniture design is not the main thing, but it’s the thing I love most.” Tayar points out that many of our most well-known designers felt the same way he does. “The reason Eames and other designers like him didn’t design too many houses is because they liked to have control over the entire piece. If it fails, it’s just a prototype when it’s a piece of furniture, and you just make it better the next time. You can’t say that to a client when you’re designing their home.”

|

|

© Tayar is especially pleased that the Calder table was created using high-tech methods to communicate half way around the world with people using ancient methods of production. Credit: Joshua McHugh

® The Calder leg supports were sand-casted in bronze by H. Theophile in Kathmandu, Nepal, utilizing one of the oldest manufacturing techniques known.

Credit: Joshua McHugh