and local labor, but on the contrary, for their enriching and inspiring traditional know how, that might be disappearing otherwise.”

and local labor, but on the contrary, for their enriching and inspiring traditional know how, that might be disappearing otherwise.”

So, began a great adventure for Adrien Gardere that spanned several years and many trips from France to various parts of Asia. “The idea was to try and understand the phenomenon where the process of production is responding to a lot of demands from the occidental world that conform to our stereotypes as to what is local or Asian or Indian, rather than a truthful and genuine reality,” he says. “It is looking for the convergence of design and sustainable design.” The process began when he won a fellowship to study and work in India. There, among other projects, he collaborated with the National Institute of Design (NID), set up in the mid 1960s in Ahmedabad, following Charles and Ray Eames’s 1958 India Report. “With 5 selected students of NID, I designed a full collection of furniture,” Gardere notes. “The idea was not to be a gimmick or a monkey design of what is exotic or local. The idea was to go very deep into the understanding of the crafts, to understand the manners and attitude of the crafts, and to see if there was an approach or technique that could be transposed, or a material that has interest, or a form that has such a strength that it deserves to be reconstituted.” This year of study resulted in seven pieces of furniture that were shown around Europe, but never went beyond the prototype phase.

About a year later, Olivier Debray, the director of Surabaya Alliance Frangaise in Indonesia, Olivier Debray, contacted Gardere to see about creating some furniture that reflected the same philosophy and approach of his Indian collection. “It was very important for me to have some local training, to root my experience in Indonesia, and to have a real exchange of know how,” Gardere says, “so I could train people at the same time that I would learn from observing.” He worked with three local design students who became his trainees.

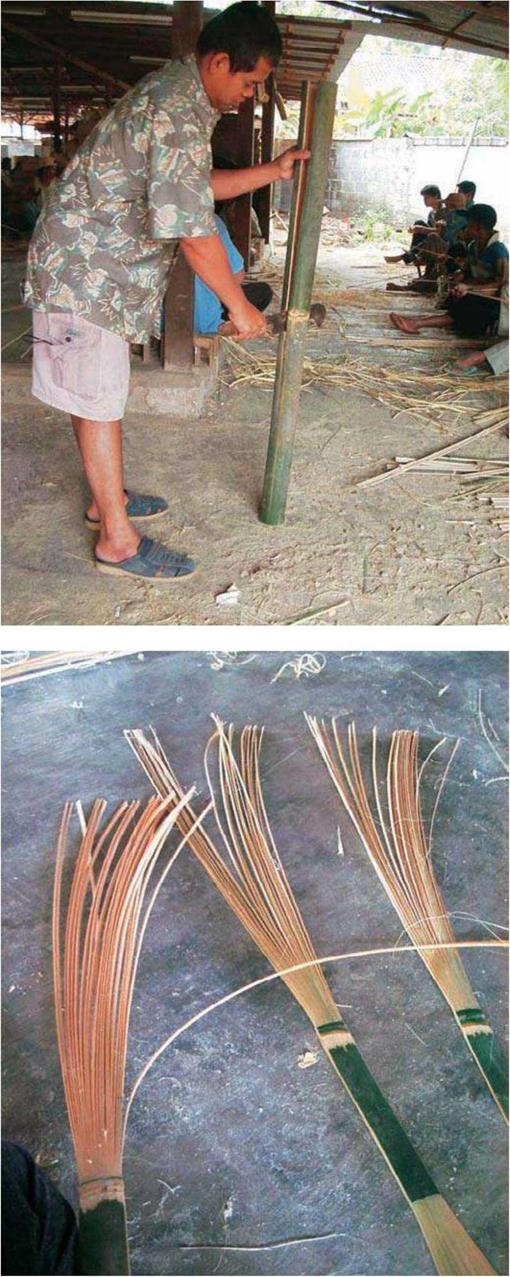

Gardere hoped that this time his creation would go beyond prototypes. “The idea was to not only identify the local craftsmen and their know how, but also to identify the local producers and the local small factories that we could follow up with and learn along the way about what we didn’t even know what we were going to make yet,” he laughs. They began by traveling the countryside looking for materials, shapes, and techniques that might be extrapolated to a chair. They settled on an indigenous, traditional Indonesian shovel that is very strong, used for a wide variety of tasks, and is made in several different sizes. “But it was disappearing,” Gardere notes. “It took us a lot of time to find craftsmen that were still making them, because they are now using plastic.” They also began experiments with splitting and

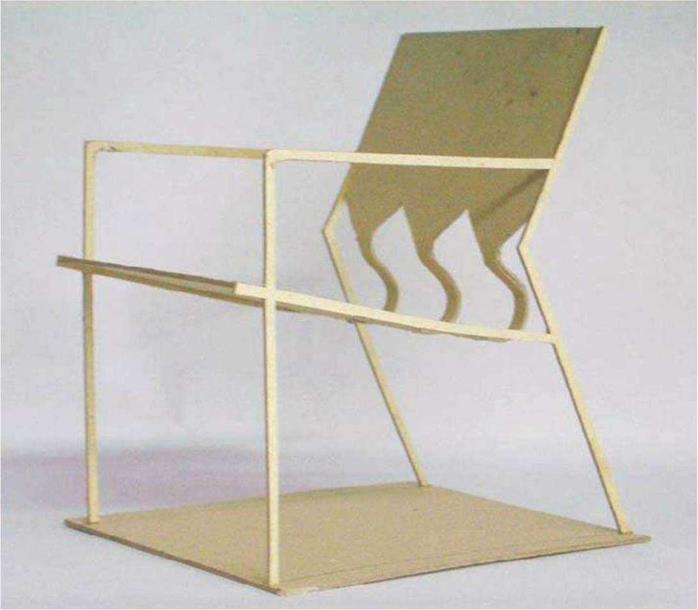

0 A “very first try on a metal frame” shows the key elements that need to come together for the final chair: bent metal, split bamboo, and woven rattan. Perhaps unfortunately, colored ribbons will not be included on final production models. Credit: Adrien Gardere

|

|

(<£) The bamboo pieces are bent in a shape that provides comfort as well as support. Early prototypes were made with whatever tools local craftsmen had on hand or could create. Credit: Adrien Gardere

|

22 DESIGN SECRETS: FURNITURE |

|

|

|

|

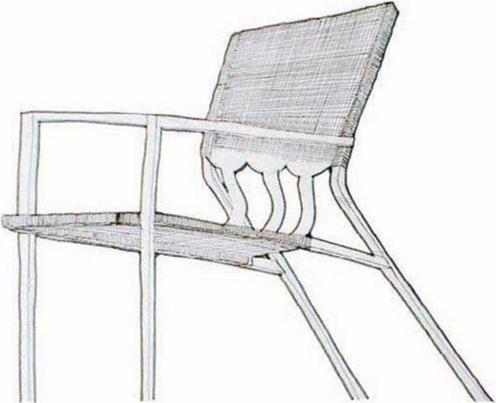

Q Gardere started with a cardboard mock-up of the chair before experimenting with bamboo, which was ultimately used. Credit: Adrien Gardere

(^) A detailed shot shows the sensual curve obtained in the bamboo structural supports, along with the delicacy of the woven rattan, which together create a very strong, versatile, and comfortable chair that uses traditional techniques to create a thoroughly modern statement. Credit: Philippe Chancel

(^) A detailed shot shows the sensual curve obtained in the bamboo structural supports, along with the delicacy of the woven rattan, which together create a very strong, versatile, and comfortable chair that uses traditional techniques to create a thoroughly modern statement. Credit: Philippe Chancel