|

T |

HE elaborations of civilisation and settled society grew rapidly during the cabriole period, and in no place more than in the dining-room. There had been splendid feasting, with every sort of device for dressing food. But the furniture of the hall or parlour where food was served and the objects for that service had been few until after the Restoration of 1660. Then, if improved methods were still lacking, it was a fault to be noted, and when Pepys sat at the “ Merchant Strangers’ table ” for the Guildhall feast on Lord Mayor’s Day, 1662, he complains that : “ It was very unpleasing that we had no napkins nor change of trenchers, and drink out of earthen pitchers and wooden dishes.” 1 By the end of the century there was not only desire for but realisation of a fuller and more specialised equipment. The trencher was gone, and until porcelain and fine earthenware became fairly plentiful, services of pewter and silver were usual. Partly by money payment and partly by exchanging “ old plate of my dear father’s,” [56] [57] Lord

Bristol acquired in 1696 dishes and plates weighing about 1,000 oz., and in 1703 u 22 new dishes & 3 dozen of plates weighed in all 1668 ounces 5 dwtt.”1 Chafing dishes and Monteith, salvers and stand, chased basket and “ large silver су stern55 he also obtained during those years. In 1705 he “paid Mr. Chambers for 12 spoons, 12 fforkes St 12 knives,” and in 1727 there come to him through the Duke of Shrewsbury’s sale “ ye case of 12 gilt knives, 12 spoons St 12 forks.”2 Such cases, habitually of wood, were often in pairs, and stood upon the side-tables. In the cabriole period they were of plain mahogany with curved fronts, but later in the century the form became straighter and there was variety and inlaying of wood veneers.

Not only the Lord Mayor’s “ earthen pitchers,” but even the large silver tankards which went round, gave way to the individual drinking vessel of glass or silver. The cabriole period saw the climax of the drink habit in high places. It was not merely the Squire Westerns, but the all-powerful and wealthy minister, Walpole, in his splendid new country palace at Houghton, who indulged in lengthy carousing after dinner. The uproar consequent on such habits causes Lady Lyttelton, when Hagley is being designed in

1 _Diary of John Hervey, Earl of Bristol, p. 147*]

2 [Ibid., p. 153.]

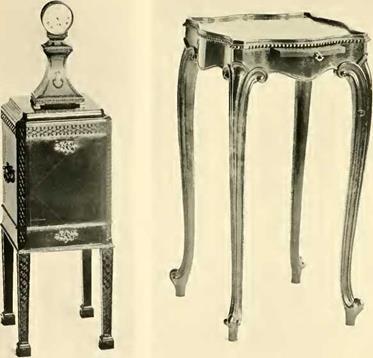

1752, to wish for “a small room of separation between the eating room and the Drawing room, to hinder the Ladies from hearing the noise and talk of the Men when they are left to the bottle.” [58] The bottle, therefore, largely governed the furnishing of the “ eating-room,” as it was then habitually called. Before the side-table became the sideboard with drawers and cupboards, a locked receptacle for bottles had to be a separate piece of furniture, and it was convenient for it to be kept under a side – table, but to run on castors so as to be easily brought forward. Such an one belongs to Mr. Percival Griffiths [P late XXIX, 1]. It is octagonal in shape, each section of side and top being a sheet of mahogany veneer of exceptionally fine figure, rich but not dark or hot in tone, and in untouched condition. The top segments start from a triple ring of ivory and ebony, and end against a string of chequy inlay dividing them from the plain banded edge. The base, so far as its height permits, fulfils cabriole forms in its curves and outlines, and is carved with foliage motifs. The top lifts to show a lead lining with divisions for nine bottles. The lining is more likely intended for drip from the bottles than for

icing, although it would admit of this on occasion, so that the piece may also be termed a wine cooler. Its lid and lock, however, fitted it for storage rather than as a receptacle for bottles in process of being emptied. For the latter purpose an open waggon on castors was devised, of which Mr. Griffiths’s example [Plate XXIX, 2] is formed like an oblong stool, but instead of a padded seat there is a fixed tray to hold six bottles or decanters. The corners of each division are high to prevent the possibility of falling out, but ramp down in curves, and the central division rises up to form a handle to direct the course of or even lift the waggon. The somewhat coarse low-relief carving of straggling design with rustic background proclaims its Irish origin, and if any gentry drank more freely than the English at this period it was their Irish brethren.

The service of tea soon became as important as the service of wine. At first it was an expensive luxury. In 1696 Lord Bristol has to pay a couple of sovereigns for half a pound ; but in 1739 he buys it in 2 lb. lots at from ібх. to 20s. per lb.1 Locked receptacles were needed for it, and tea caddies of various forms and materials were freely produced. Silver ones, in Chinese style within shagreen silver-

1 _Diary of John Hervey, Earl of Bristol, pp. 144,

56.]

mounted cases, were for the wealthy, while a simple mahogany box to hold a couple of little canisters served for lesser folk. Tea was black and green, so that at least two canisters were needed. As tea became more plentiful, and was bought and used in greater bulk, the caddy was enlarged and set on legs, and the u nabobs ” brought the name of teapoy back from India. It was a corruption of a Hindu word for a tripod, and by erroneous association came to mean the receptacle, on tripod or other form of stand, in which tea was kept. When, in the middle of the eighteenth century, the example illustrated [Plate XXX, i] was made, the name was not yet introduced, and it was probably merely called a caddy on legs. It is a mahogany box with receding raised top and chamfered angles and enriched with Chinese fret. The chamfer has a stop at the base where it joins the straight leg, down which the ornament is not fretted, but only slightly incised. Lifting the top, we find four metal canisters, square except at one angle which follows the chamfer of the box. Two of the canisters have little round apertures rimmed to take a cap ; the others have flat hinged tops, the former being for the teas and the others probably for sugar. The oak-leaved escutcheons are charming, and have never suffered from relacquering any more than the mahogany surface from repolishing. With tea-drinking came in silver kettles with lamps, of

which Lord Bristol bought one in 1698.[59] Urns with taps, and heated by an interior iron, replaced them towards the close of the cabriole period. It was especially for the latter that stands were devised, fitted in front with a little draw-out shelf whereon the teapot could stand just below the tap of the urn. The example shown [Plate XXX, 2] belongs to the closing years of George II. The legs are only slightly cabrioled, the knee and its wings being a mere swelling out of the ribbing that starts from the French foot. The sway of the curve is continued wave-like in the lines of the top, which, above a beading, has a raised edge rather than a rail, for it onlv rises a quarter of an inch, but is sufficient to prevent the urn slipping off. Of the same shape is the top of another one, belonging to Mr. Griffiths, except that it lacks the raised edge, and its straight fluted legs proclaim it of the Sheraton period. A width of 11 in. and a height of 22 in.—a little more or less—were the regulation sizes of these elegant little pieces.

The distance between kitchen and eating-room was apt to be enormous in Georgian houses, and, as at Stoke Edith, there was often between the two a

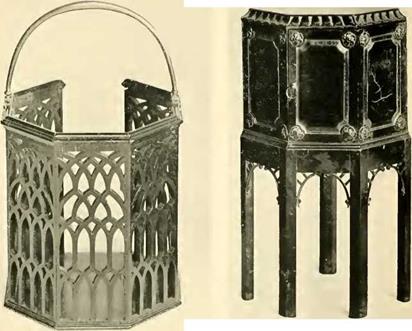

resting-place with a hot plate. If there were no steps a wheeled waggon might be used for transport. But the eating-room was frequently placed on the first floor, and hand carriage was necessary. Handled cylinders were, therefore, devised to bring the plates. The choicest of these skeleton pails were mahogany octagons, with one open section for the convenient handling of the plates, and the rest of open fretwork, resembling in simplified form the various devices of chair backs. The one illustrated [Plate XXX, 3] is in the “ Gothick ” manner, but Chinese frets and various scroll-pattern devices were also used. They were generally in pairs, and, standing by the fire, kept the plates warm till they were needed. Tiered waggons, or dumb waiters, and corner commodes, such as the one illustrated [Plate XXX, 4], were among the paraphernalia which went to complete the well-appointed eighteenth-century eating-room.

|

T |

HE word cabriole, although convenient, is not without it faults as denoting the period of English furniture under review. It was not used contemporarily and is insufficiently comprehensive. It relates to a single member and not to the whole of any piece of furniture. It draws too large a measure of attention to the leg and so away from the all-enfolding principle and spirit of the style, which, at its best, is the apotheosis of the curved line. Rightly treated and understood it shows that line in its self-sufficiency and inclusive completeness— running from base to summit, spreading laterally and co-ordinating under its supremacy every item and corner, exhibiting a continuous, connected suavity, whether in main line or little detail, whether in ocean wave or pool ripple. Although it came at the moment when baroque exuberance was assuming rococo extravagance, it was, while refusing the straight line, a reserved style, and only when sumptuousness or eccentricity was demanded did exuberance confuse its line, and extravagance load its ornament. Certainly it did not depend on such elaborations for success, and often they marred rather than heightened the effect. Simple pieces, devoid

73

of carved enrichments, such as the Queen Anne chair on Plate VII, 2, or the George II urn-stand on Plate XXX, are satisfying, distinguished, aristocratic. Fine material, masterly design, consummate workmanship could produce blue-blooded gentility, unquestioned and self-evident, without the trappings of regal costuming or the splendour of pompous circumstance. Simplicity without commonness, dignity without display, are the characteristics of a great deal of the output of our eighteenth-century cabinet-makers. But with this intelligent capacity for effective reticence there struggled a desire to worship alien gods, a striving after the new, the varied, the unexpected. Guided by the master hand these elements might be subordinated to useful service, but allowed to dominate by the weaker brethren they could only produce anarchy and disorderliness in the realm of decoration.

Efforts to get variety and originality into the somewhat austere and limited framework of Vitrurian rule and Palladian precept had produced the baroque style in Italy as early as the sixteenth century. A rich realism, an importunate vivacity of movement in human and other forms, a sheer cleverness trampling over structural reasonableness had been among its elements. These had grown stronger in the seventeenth century, and had invaded all Europe, although exercising limited power over the earlier exponents of the late Renaissance style in England, where, as

74

we have seen, a large measure of sobriety prevailed in the sphere of decoration and furniture in the eighteenth century. Yet, at that time, joy in excess, in invention, had called to its aid the distant both in time and space. The archaeology and the romance of mediaevalism began to have their votaries and the “ Gothick ” taste crept in. The imports of the East India Companies were making known Oriental. wares and customs and the Chinese manner became fashionable. In its “ gay and tortuous forms ”[60] the votaries of the combination of realism with movement could revel. Indeed, in some of their designs they appear drunk with it. It was towards the close of the cabriole period that cabinet-makers took to publishing books of designs, and as they could engrave even wilder conceptions than they could produce, these books show us not so much their actual output as their unrealised aspirations. In the publications of Edwards and Darley, of Mayhew and Ince, of Lock, of Johnson, and even of Chippendale, we find whole congregations of C scrolls intent on a joy day. In company with Chinamen and dragons, birds and beasts, they wriggle, scamper or sit about rocks and cascades, trees and pagodas, seeking release from encompassing

swags and wreaths of fruit and flower, leaf and shell. Looking-glasses and china shelves were the chosen fields for these tangled crops, but side-tables came near, while chairs and cabinets were apt to have their pagodas and bells, their rails and frets, their own ample measure of the “ tortuous.”

The “ Gothick ” taste, if less riotous in its manifestations, was capable of being more obtrusive, as its forms were more definite and at the same time more antagonistic to the classic style which still ruled in structure and general design. There was not at this period any attempt, scarce, indeed, any dawning desire, to supersede the style which Inigo Jones had brought from Italy by the Gothic or the Egyptian, the Arabic or the Chinese, in severalty or in common. They were trifles for the curious, playthings for a slightly blase, but quite active – minded society, and were used merely as a sauce piquante to the solid joint of which it was tiring. Sanderson Miller would erect sham castles and ruined abbeys in his friends’ parks, but when they asked him for a serious house, as Lyttleton did at Hagley,[61] he designed it rigidly within the style which we call Georgian. Yet, just as the subsidiary architectural effects in park and garden might be

touched with exotic “ whim-warns ”—as Gray called them 1—so could these be called in to deck interior furniture and decorations. “ They might, without discordancy, provide the traceries of a bookcase or enrich the mouldings of a Chippendale table.”[62] [63] Where the cabinet-maker used the innovations with discretion and taste they gave an agreeable and justifiable fancifulness to his productions.

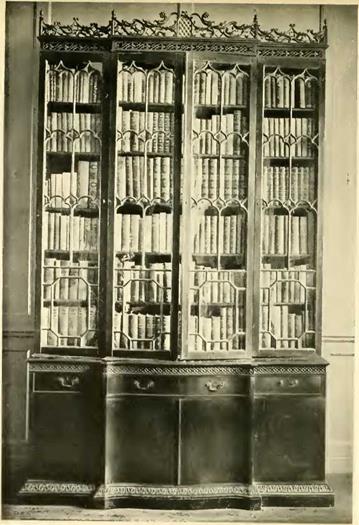

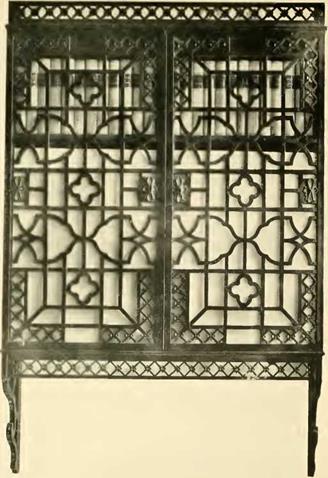

It is such pieces as these, and not the eccentricities of the age, that Mr. Percival Griffiths has collected to represent this phase of the cabriole style. The bookcase now illustrated [Plate XXXI, i] is in strong contrast to the writing cabinet with top [Plate V]. That has a full architectural character in the classic manner of its age, whereas the bookcase has drawn its decorative motifs from various anti-classic sources. The tracery of its glazed doors is Gothic, the fretting of its friezes is semi-Chinese, its cresting is mainly composed of rococo scrolls, which carry out the cabriole spirit of the curve as does the waved front of the lower doors. The structure is dignified, serious, and within architectural rule, without having architectural feature. The same may be said of the hanging china cabinet [Plate XXXI, 2], a representative

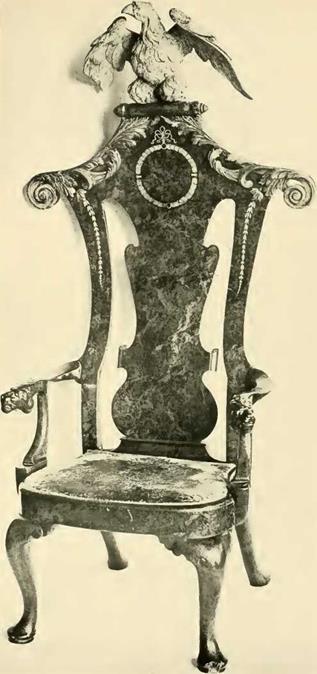

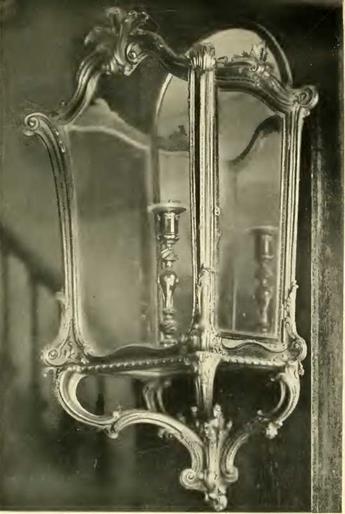

specimen of the temperate use of the Chinese fret. Such fret used as the enrichment of a solid surface we again find in the little case or cupboard that encloses an Italian cabinet [Plate XXXII, i], whereas the frieze of the stand is Gothic and the cabriole legs have the acanthus scroll derived from Italy. That also is the basis of the enrichment of the candle lantern [Plate XXXII, 2], which is a choice and admirable example of what has been laid down as the basic principle of the cabriole style—the apotheosis of the curved line. The design is so well thought out, the tendency of the curve to run amuck, to stray beyond due decorative bounds, is so well checked and disciplined, that the geometric and structural sense is fully satisfied without recourse to a single straight line except the very inconspicuous one at the base, which itself is modified by gadroon – ing. The lantern is one of a pair that was in the collection of the Hon. F. S. O’Grady, of Duffield Park, Derby, which came under Christie’s hammer in April 1912, when these pieces were catalogued as :—“ A pair of Chippendale mahogany Lanterns with glass fronts and sides and looking-glass backs ; the frameworks carved with foliage and fluting and supported beneath by four carved scrolls : 34 in. high : from Coventry House, London.”

The sensuous libertinage of form and decoration that was reached by the rococo extremists led to a

reaction. Recourse was again had to the classic past by the reformers, and direct reference to ancient Greece itself was the chief source of inspiration. Hence the style called Louis XVI in France, and which in England is bound up with the names of Robert Adam, as an architect, and of Sheraton, as a furniture designer. The straight line again prevailed, but with an added fineness and reserve. It stood for intellectual elegance tinged with puritanism.

|

|

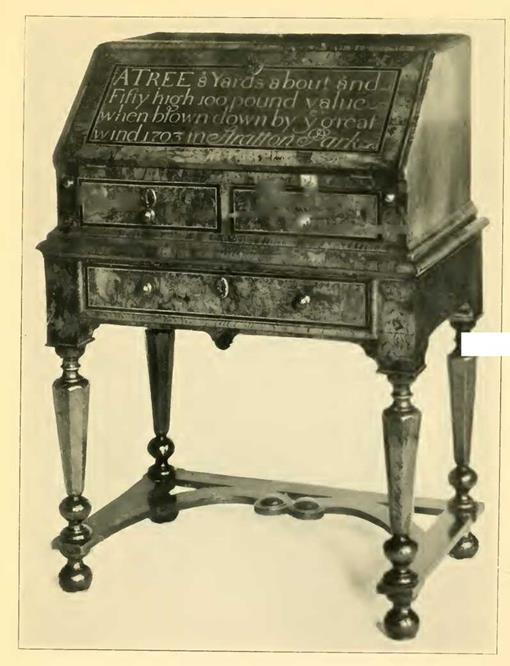

Writing Desk on Stand : Walnut, with Pear Lettering and Pear and Ebony Banding*

Width 23" at Top; a Late Example of the Straight William III Leg. c. 1710.

|

Small Writing Bureau with Legs : Walnut, with Pear Banding. Early Example of Cabriole Leg with Ball-and-Claw Foot. c. 1710-15. |

|

|

|

Bureau-Dressing-Table : Mahogany, Carved in Low Relief.

The Writing Flap pushes back to disclose the Dressing Apparatus ; the Central Cupboard pushes back to give Knee Room. Height 32},", Width c. 1750.

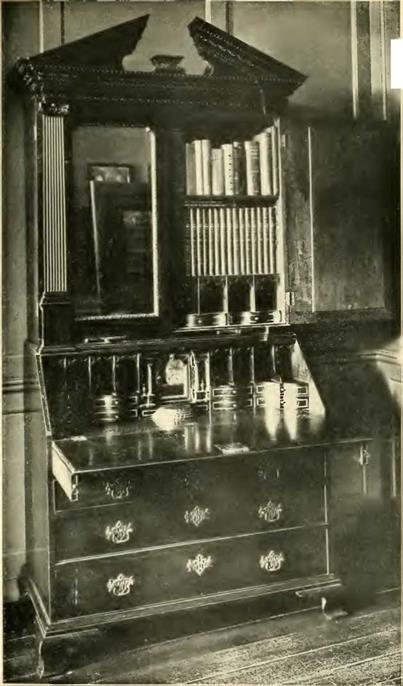

Mahogany Writing Cabinet.

The Upper Part fitted for Ledgers, Books and Documents, the Flaps falling forwards to disclose Drawers, Pigeon-Holes, with Secret Receptacles behind them. Width 6". c. 17

|

|

|

|

Double Chest of Drawers : Mahogany.

The Frieze and Chamfered Edges carved with Chinese Fret, with Pagoda topped Fretted

Plates, 6′ і У’ High X 3′ oi". c. 1750.

|

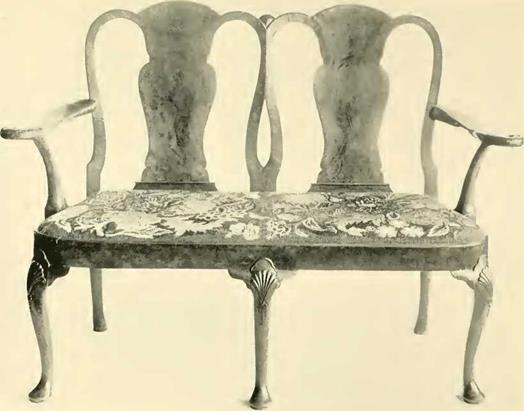

Large Walnut Settee, highly Finished and Ornamented.

The Triple Hack is unusual, especially in Walnut. Extreme Length, 6′. c. 1^30.

|

|

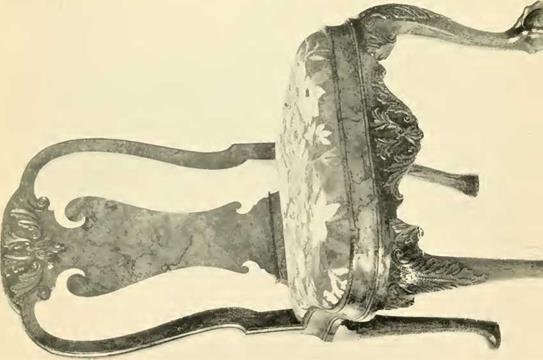

Child’s Walnut Ann Chair, covered with Velvet.

Height to Seat, 11"; Total, 2}". c. 1725.

I

Mahogany Writing Chair.

Rather Small for its Type. Back Leg Uniform with others. Sides of

Seat 15", Total Height І0!”, c. 1745.

|

|

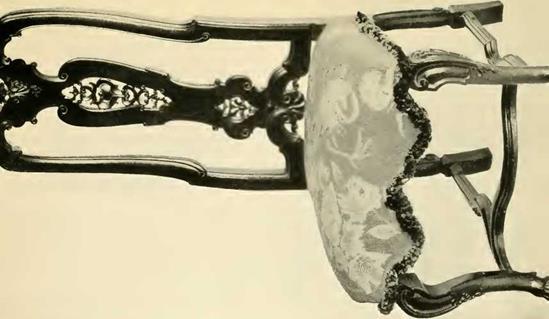

Walnut Arm Chair with wide Upholstered Seat and Back, Carved L:gs,

Needlework Contemporary, but not Original, probably Scotch.

Seat 28" Across, 2,1" Deep. c. 1740.

|

|

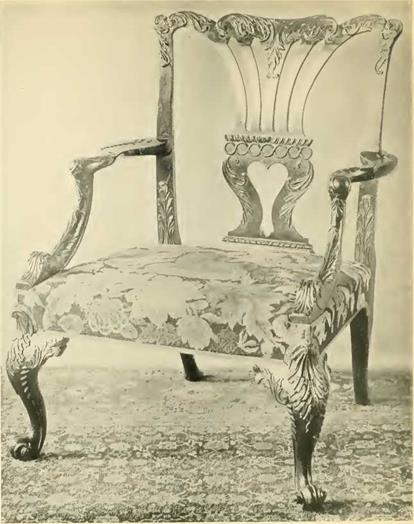

Mahogany Chair, Arm Supports springing from the Corners of the frame.

Raking Back, High Cresting to Knees, “ French ” Feet.

Seat 27" Across, гг" Deep. c. 175°-

Walnut Stools with Clavv-and-Ball heet, c. 173°*

i. With Round Scat Upholstered in Needlework over the Frame i in Diameter. z. With Oblong Movable Seat Pitting into Rebate of Piame.

Mahogany Stools.

i. Spinet Stool, l. egs with Ribbed Leafage running down from the Knees, and Claw-and-llall Feet, Kidney-shaped Seat. 13J X 9 . c. >7i5-

2, Chippendale Chino-Gothic Style, Legs carved “a Jour,” Seat-Rail below Upholstering Decorated with Cusped Arcading, Oblong Seat with Slightly

Serpentined Sides. 24!.” X c. 1"“5 ^-

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

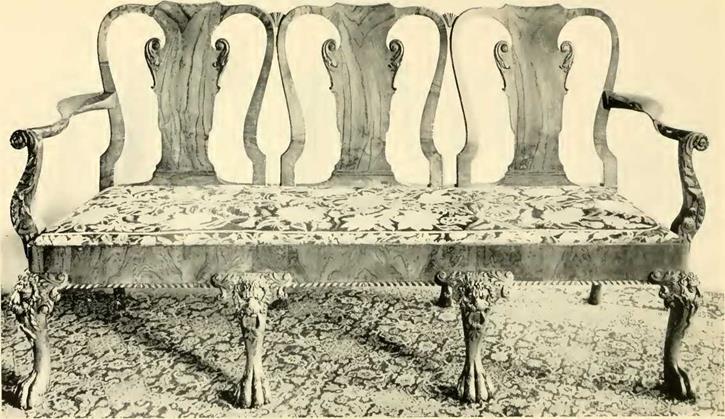

Small Mahogany Settee of Two Chairback Type, with Single

Central Upright.

Seat 43" Long. c. 1-50.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

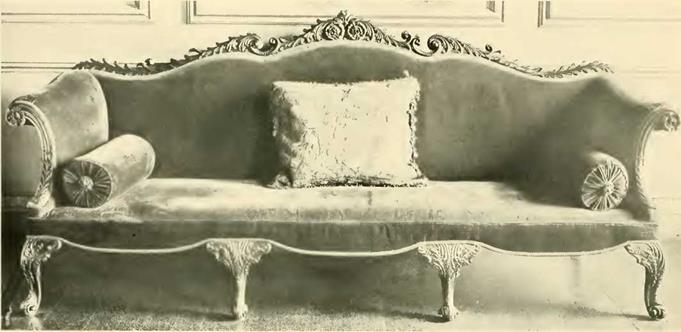

Large Mahogany Sofa with L^pholstercd Back, Sides and Seat, Richly Ornamented Frame, “ French ” Feet with Upright Leaf.

S’ Long, F 7" at Centre of Back. c. 1760.

Round Flap Dining-Table, Lion Mask on Knees and Ball-and-Claw Feet.

Diam. 58", Height 28". c. 1730.

Side-Table with Breche Yiolette Marble Top, Ball-and-Claw Feet, Wave Pattern Frieze, Elaborately Carved Apron.

64" X 32", Height 35". c. 1730.

|

Tea or China Table.

A very strong Table in spite of its extreme Elegance, Delicately Fretted Rail. Top 30" X 21". c. 1750.

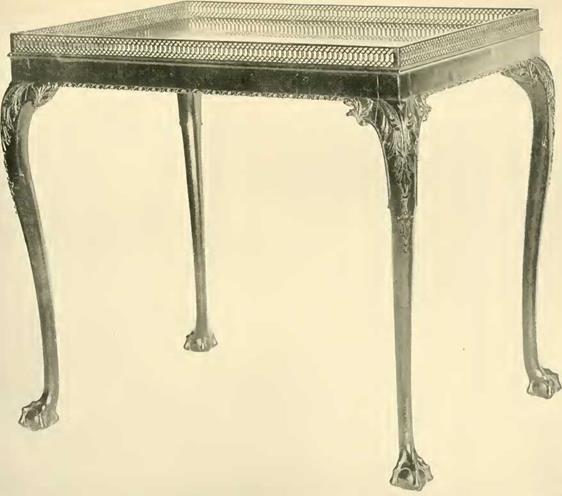

Galleried Table on Tripod Stand.

![]() The Gallery is exceptional in its Solidarity and Ornateness.

The Gallery is exceptional in its Solidarity and Ornateness.

|

|

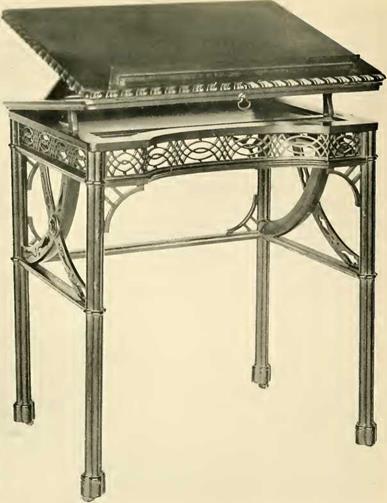

Cluster-legged Drawing Table.

Its Lightness and Elegance imply that it was made for a Lady Amateur, c. 1750.

|

|

|

|

Card-Table of Chippendale’s “ French ” Type.

The Choice Nature of the Figured Walnut Veneer is the Excuse for so late a use of this Wood, c. 1750.

|

|

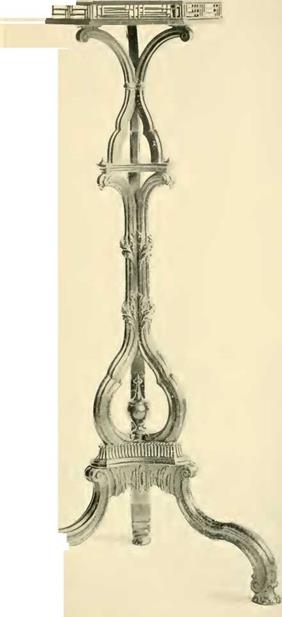

Candelabra Stand and Candle Screen.

Candelabra Stand and Candle Screen.

Candelabra Stand, 4′ 1" High, c. 1755.

|

|

Mahogany Tripods and Candlesticks, c. 1725.

i. Candle Stand, 2С. У’ High, Top 11" Across. Candlestick, 2. Candle Stand, 29" High, Top 13" Across, edged

1°" High, with Rase 5’" Across. with Reading. Candlestick, 1S" High, y}/’

Across Rase. Acanthus Carving and Rrass Top.

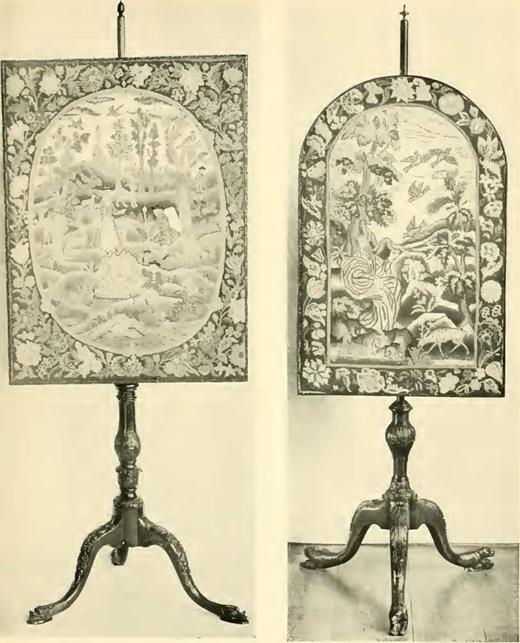

Mahogany [Pole

Mahogany [Pole

Screen, 5′ V’ High ; Needlework Panel, 26" X?4" ; the

Feet shaped as Dolphins, c. 1-25.

|

|

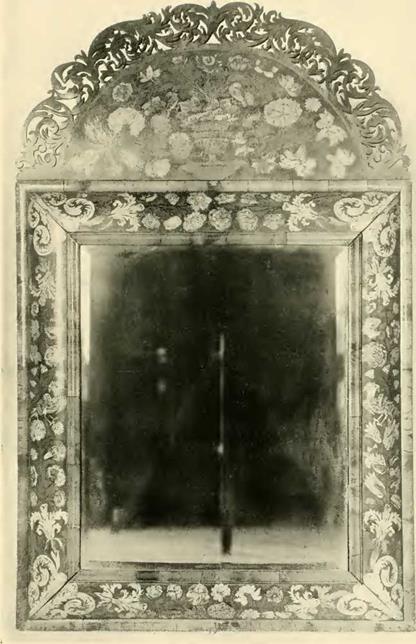

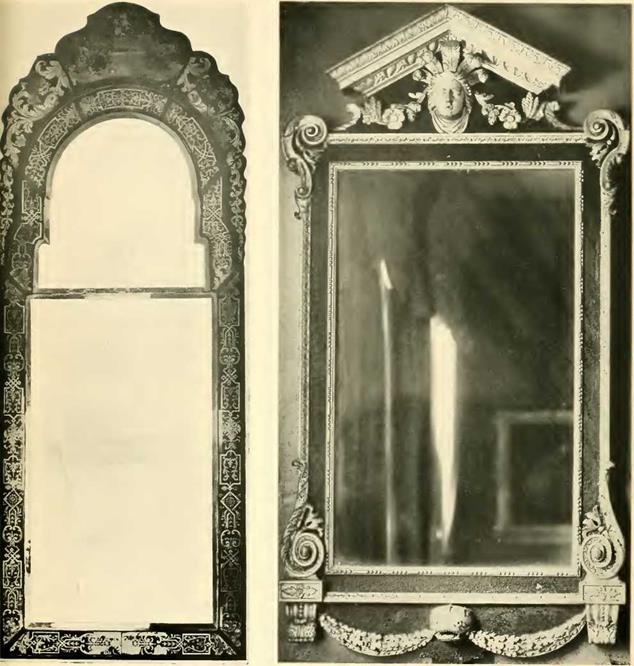

Mirror in Marquetrie Frame.

Original Bevelled Plate, 2! оX 1′ 8". Frame, 5-і" in Width. Size over all,

4′ За" X F 7V’. c. 1700.

|

|

![]() Mirrors.

Mirrors.

2. In Carved Gilt Wood Frame ; the Ground Sanded and, at some time, Blacked over the Gilt, which shows through, giving a Green Tinge. Plate, 3′ 3" X 1′ it". Size over all, з’ 4^" X z’ 9J". Style approaching that of William Vent, c. 1725

Collarette and Wine Waggon.

Collarette and Wine Waggon.

2. Mahogany, to hold Six Bottles or Decanters. Ball-and-Claw Legs, Knees and Apron roughly Carved with Foliage, Flower and Shell in the Irish Fashion. Height 20.W; Width 20". c. 1 745.

Urn Stand.

Urn Stand.

Mahogany, Scrolled Cabriole Legs, French Feet, Beaded Fldge and Slight Rail. Height 2if"; Width 11". c. 1750.

|

|

Plate Pail. Corner Commode.

Mahogany, Octagon with one Open Section to lift Mahogany, Pagoda ‘Гор, Straight Legs with Plates, the others pierced with “Gothick” Pattern. Chinese Fret in Angles; Rosettes carved

Height 12г,"; Width 11". c. 1750. at Corners of Revelled Panels. Height

26"; Width 11". c. 1745.

|

|

Mahogany Bookcase, composed of Centre and Wings.

1 he Tracery anl Friezes influenced by Gothic and Chinese Tastes. The Cresting a Rococo Arrangement of C Scrolls and Foliage. Total Height </ 2", including the 6" of the Cresting. Width of centre 1′ y", of each wing 1′ 4}/’ ; total C 6". c. 175^.

Hanging China Cabinet, Mahogany.

‘1’lic Doors ami Rails Open Fretwork in the Chinese Manner. The Sides with

Chinese 1-ret carved on the Solid. I otal Height ^ ; Width z’. c. 1750.

|

|

С. і52 on Stm. I co. iraitiin* an Italian Cabinat.

Mahogany, the Case enriched with Chinese Frets, the Rail of the Stand with a Gothic Arcading "carved on the Solid. ‘The Legs of Cabriole Form with French Feet and Acanthus Scrolled Kmees. The Cabinet of Wood with Gilt Design on Dark Green Background, Framing Marble Panels, The Frieze and Columns also of Marble, the Capitals Wood Gilt. Total Height з’ S"i; of th; Case i’ +V’-; Width i’ 5^". c. 1745.

Candle Lantern, One ot a Pair,

1 [Encyc. Brit., nth edition, V, 801.]

[3]S

[4] “ There was prepared (at Wilton) for his highness, at the head of the table, an arm chair, which he insisted upon the young lady’s taking; upon which the Earl instantly drew forward another similar one, in which the serene prince

[5]3

sat, in the highest place; all the rest sitting upon stools.”—Magalotti, Travels of Cosmo the Third, London, 1821, p. 150. The same thing occurred at Althorp, pp. 248—9.

[7] That year’s accounts have been photographed, and a set bound together will be found in the library of the V. and A. Museum.

[8] [MS. Accounts, 1698 volume, S. Paul’s

[9] [John Wheldon’s account book, Chatsworth Library.]

[10] [Macquoid, History of English Furniture, Vol. Ill, fig. 104.]

[11] [Chippendale, Director, 1762 ed., plate XIX. ]

27

[12] This arrangement had a queer look when Mr. Griffiths acquired the chair, for at one period its owner had a fancy for the loose seat and rebate type, and had veneered the rail with mahogany of very different quality and colour from the rest of the chair. By this and from the nail-marks at the base of the arm supports his tampering was quite evident, and Mr. Griffiths has very properly given back to it its ancient appearance by re-upholstering over the rail with old needlework.

28

[13] [Evelyn, Misc. Writings, p. 700, 1825 ed.]

[14] [Duclos, CEuvres, Vol. V, p. 33°.

[15] _Diary of the First Earl of Bristol, p. 137.]

29

[16] [Magalotti, Travels of Cosmo the Thirds London, 1821, p. 150.]

[17] [Hervey, Memoirs, Vol. II, p. 117.]

[18] [Congreve, The Way of the Worlds Act IV, Scene i, produced in 1700.]

[19] _New Eng. Die., under Couch.]

[20] [John Weldon’s account book, Chatsworth Library.]

D

1 [Evelyn, Misc. Writings, 1825 edition, p. 700.]

[22]

[23] [Magalotti, Travels of Cosmo the Third London, 1821, p. 278.]

[24] [Roger North, Lives of the Norths, 1825 edition, Vol. I, p. 276.]

[25] [R°ger North, Lives of the Norths, 1825 edition, Vol. I, p. 272.]

[26] [Illustrated by Mr. Macquoid, Age of Walnut,

Fig- 33-] .

[27] [Illustrated by Mr. Macquoid, Age of Mahogany, Fig. 42.]

[28] [Illustrated in Country Lfe^ Vol. XXX, p. 97.]

[29] [Evelyn, Misc. Writings, 1825 edition, p. 700.]

[30] Diary of Johti Hervey, Earl of Bristol 1894,

P – 39-]

[31] [.Director, p. xiv.]

[32] Paston Letters, Vol. Ill, p. 314, 1875 edition.]

[33] [Evelyns Diary, Feb. 5, 1685.]

44

1 [Macquoid, Age of Walnut, Fig. 115.]

1 [ Rape of the Lock, Canto III, lines 43-4.]

[36]

[37] [Farquhar, Sir Harry JVildair, Act II, sc. 2, first performed in 1701.

[38] [Correspondence of Lady Hertford and Lady Pomfret, Vol. Ill, p. 103.]

[39] Rape of the Lock, Canto III, line 105.]

47

[40] [Director ^ Plate CXLV, 1762 edition.]

5°

[41] [Bishop Hall’s Meditations, p. 282, 1635 edition.]

1 [.Director, Plate LV, 1762 edition.]

[43]

[44] [Hampton Court Palace accounts, 1699.]

[45] [f)iary of fohn Hervey, Earl of Bristol, 1694,

P – H3-]

[46] [c< Large looking-glass richly japann’d.”—Evelyn, Misc. Writings > 1825 edition, p. 700.]

57

[47] [See Country Life, Vol. XXX, p. 712.]

58

[48] [Ham House MSS.]

[49] Evelyris Diary, ed. Wheatley, Vol. II, p. 322.]

[50] [Allen, History of Lambeth, p. 371.]

59

[51] [John Weldon’s account book, Chatsworth Library.]

[52] [C. Simon, p. 169.]

1 JLord В r is to Гs Diary ^ p. 146.]

[54]3

[55]5

[56] Pepyss Diary, ed. Wheatley, Vol. Ill, p. 321.]

[57] ГDiary of John Hervey, Earl of Bristol, p. 144.]

66

[58] [Lilian Dickins and Mary Stanton, An Eighteenth-Century Correspondence, London, 1910, p. 284.]

[59] [“ Paid Mr. Chambers his bill in full for a Tea Kettle and lampe.”—Diary of John Hervey, Earl of Bristol у p. 145*]

[60] [Geoffrey Scott, The Architecture of Humanism, p. 43.]

[61] [Dickins and Stanton, A? i ILightee? ith-Century Correspondence, p. 287.]

[62] JLetters of Thomas Gray, ed. Tovey, Vol. I, No. CXIV.]

[63] [The Architecture of Humanism, p. 46.]

77