“When you design an object,” he continues, “you will always have someone else who will come in the process, and say, ‘Sorry Patrick, you can’t do it like this because our machine won’t do this.’ So I change it. I don’t want to, but I have to find a solution. Or the manufacturer will say, ‘I can’t sell this, the market will not accept.’ But this time, there is no technical constraint, and no one in the middle of the process. It’s now a pure idea; not cooked, but raw. Which is why it looks so incredible.”

“When you design an object,” he continues, “you will always have someone else who will come in the process, and say, ‘Sorry Patrick, you can’t do it like this because our machine won’t do this.’ So I change it. I don’t want to, but I have to find a solution. Or the manufacturer will say, ‘I can’t sell this, the market will not accept.’ But this time, there is no technical constraint, and no one in the middle of the process. It’s now a pure idea; not cooked, but raw. Which is why it looks so incredible.”

jouin is referring to the freedom he found when he began creating functional objects with a process normally used for rapid prototyping. Jouin first became familiar with stereolithography when he was designing a decorative object for a Las Vegas bar. “To make the model,” he says, “it’s very hard to describe for the mill worker, so it’s best to make a prototype. It’s all about the power of the 3D programs and 3D rapid prototyping. After I saw the pieces materialize, now I knew very well the process and I see a great opportunity, not to manufacture, not just to design an object you look at, but to make something you really use —a chair, or a stool, or a table.”

While rapid prototyping has been available in various forms of technology, new advancements in stereolithography made Jouin’s vision possible. “There was no machine to manufacture a big object like this when we started to design,” Jouin notes. “The mammoth machine was just being made to produce larger objects in stereolithography. It was the coming together of this new technology that allowed an ultra freedom with shape, which is totally new for a designer.”

Stereolithography is a process that quickly turns a 3D CAD file into a physical object. It works by tracing laser beams over the surface of a vat of liquid photopolymer. The laser instantly cures one slender layer of the photosensitive polymer resin at a time; each layer adheres to the previous one, thereby creating the object. Jouin uses a low-tech metaphor to explain this high-tech process: “I can describe it also another way, very simple,” he says. “You will print an image with your laser printer, okay, and each time there is a very thin layer of powder or ink. If you put the same page again and again in the machine, every time there will be some ink that will go on top of the other layer of ink, and if you do it thousands and thousands of times, you will have a real 3D piece made of ink.”

|

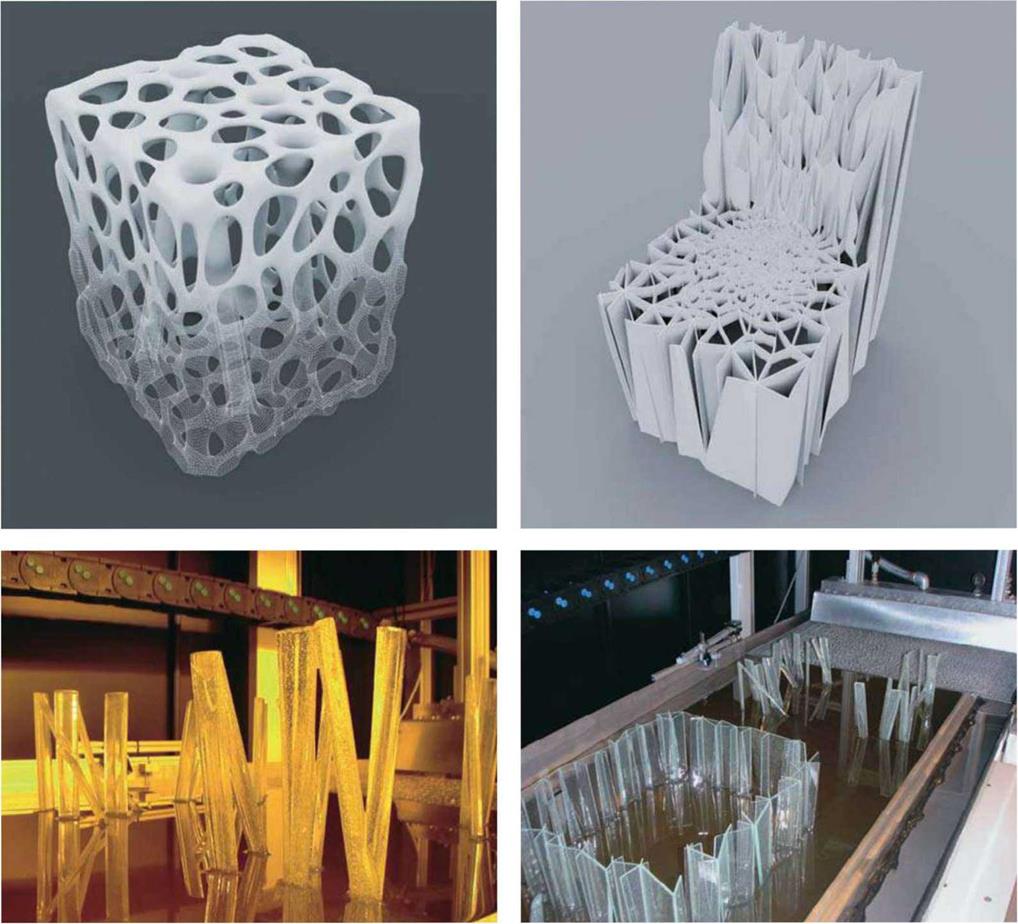

<2> Top: A rendering of the Solid stool depicts how stere – olithogrpahy allows a designer to go directly from a 3D CAD drawing to a product, without molds or traditional manufacturing processes. Credit: Thomas Duval

Bottom: In stereolithography, a laser cures the surface of a vat of photosensitive polymer resin; the next layer adheres to the first and the object is built like a sedimentary rock. Credit: Thomas Duval

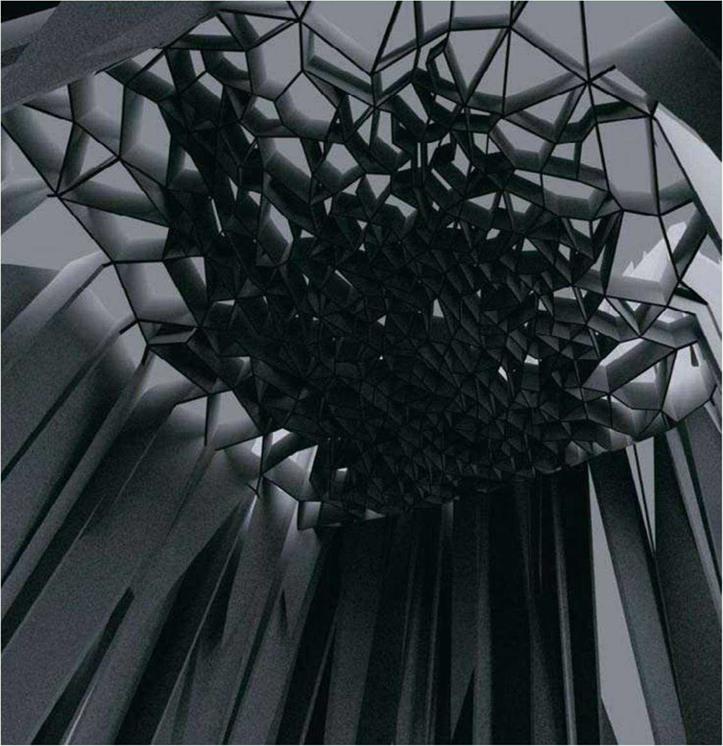

(a) Top: Too fragile to put into production, this prototype of the Ci chair shows how stereolithography allows fantastic structural ideas to be the guiding design concern. Credit: Thomas Duval

(A) As the laser hardens each slender layer of polymer, the whole piece is lowered into the bath where the next layer is carved out of the liquid. Credit: Thomas Duval

|

The organic rather than built nature of the process forced Jouin to rethink how he designs. “The idea wasn’t to design an object, but to invent a structure and how they grow. It’s really linked to nature,” he says. “When a tree grows, even if it has no brain, it will totally react to the environment, it will look for light and water, and it will adjust its shape with the condition. And so, the idea was for the ribbon chair, I have on the floor a number of grasses and they grow, and they want to take the shape of a chair at the end. When they are 17.5 inches (45 cm) from the floor, then they become a seat, then they become a back, and then a leg. But they are too fragile,” he continues, “so, some other grasses come and grow and support them and triangulate the structure.”

The ribbon, or Solid Chair is just one of several objects jouin created using stereolithography. He points out, “The technology is not very simple to understand, but as a designer, you have to understand it very well to design something interesting. Because, if you really look carefully, no craftsman can do it. It’s impossible.” He quickly corrects himself, “Nothing is ever impossible, but it will take the genius of a sculptor to work for thousands and thousands of hours to do one object. This is almost impossible. But the machine can make anything I want. Maybe it’s not comfortable, and I can’t sit on it, but if I want, I can do it.”

For jouin, stereolithography forces a rethinking of several key assumptions in how we consider design styles. “All modernity is based on the reaction against the bourgeoisie, the luxury, everything made by hand and craftsman,” he explains. “And this time, you can do something super complex or not complex at all—it’s

up to you, the machine does what you want. This technology is more for complexity. And this is the important point, because now complexity is not antimodern. Because it is a machine that is producing this complexity.”

It is this convergence of idea and technology—and the immediacy it offers—that intrigues Jouin. As he explains in a small booklet he published, “What this experiment shows, above all, is the telescoping of design technology and production technology. It is part of a general trend towards immediate materialization of the object: the amount of time separating the idea —which used to be nothing more than a presage, a vague specter of the thing—from the three – dimensional object is shrinking. Soon, no one will be involved but the designer and the machine—the design process will immediately plug into the production tool.”

Jouin says working with stereolithography has been “a break for me. Because I was more working on the skin and the surface of objects and this time we are working on structure. Sometimes I discover with this project that I am more free than ever. I show to myself that I can do what I want. And there is no barrier.” Again, he pauses to correct himself. “There is always a barrier. It was beauty. I always tried to make something beautiful, and this time I didn’t care.” After all, with this means of collapsing the time it takes to move from idea to final object, paradoxically, the final product matters less than how it came about. “It’s an adventure,” Jouin says. “I am more happy about this, to discover something new. After this, I am less interested in objects; it’s more the process, the adventure, than the result.”

|

118 DESIGN SECRETS: FURNITURE |

|

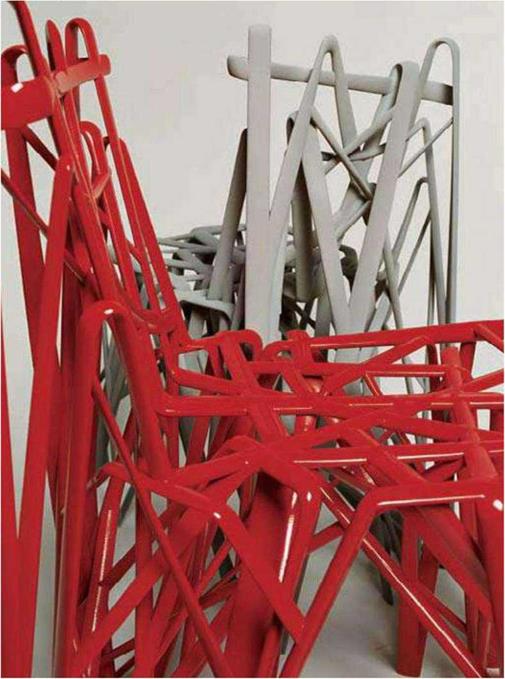

© The Solid Table uses triangulation of the various ribbons to create a structure that is solid enough to stand up and support a glass tabletop.

Credit: Thomas Duval

Q) The rapid prototyping process used to fabricate the Solid Chair allows the designer to create pieces in any form, without considering the usual limitations of more typical manufacturing techniques.

Credit: Thomas Duval

Credit: Thomas Duval