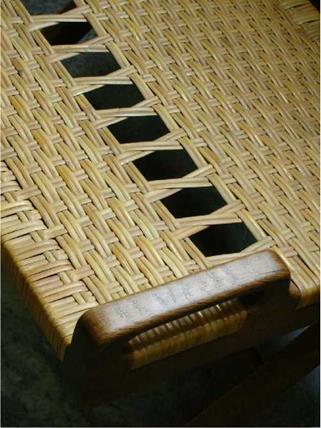

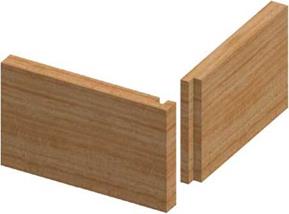

The way materials, hardware, and components come together is key to creating great furniture. The expressed joint is the beginning of ornament (Figure 8.15). At a utilitarian level, the joint must be strong enough to resist the forces placed on it. This is especially important because the joint is often the weakest point of a fabrication. Yet, the joint can be more than a means of joining material together. There is an opportunity to communicate meaning through joinery. It is also important to consider the aesthetics of the expressed joint resulting from structural necessity and resulting in patterns of visual delight.

Consider the techniques of detailing or joining together two or more elements. Broad

Consider the techniques of detailing or joining together two or more elements. Broad

categories of joining materials include:

■ Adhesives

■ Mechanical connections:

Sewing

Nails, rivets, and staples Threaded fasteners Snap fits

Applied hardware

■ Combining adhesive and mechanical connections:

Dado Dovetail Finger joint Miter joint Mortise and tenon Rabbet

■ Welding:

Spot and arc welding Brazing

Metal inert gas (MIG) welding Tungsten inert gas (TIG) welding Diffusion and glaze bonding

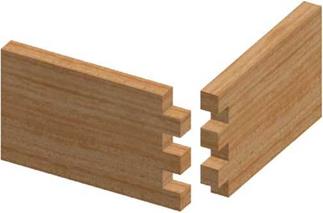

Adhesive joints are virtually seamless unless the edge profile of the connection is made visible. Laminating Figure 8.15 Finger joint. Photography by Jim Postell, 2006.

high-density plastic laminate upon a %-inch (2-cm) MDF substrate and a simple butt joint of two similar woods are examples of adhesive joints. Wooden tabletops built up from strips of lumber do not need to be pinned or mechanically held in place with biscuits. Today’s wood glues are sufficiently strong to do the job alone; they are able to hold the top of a table together for the life of the table.

Mechanical connections rely on a variety of joining materials and methods. Sewing is the earliest method for joining material. Consider the ancient leg connections made by wrapping wet leather around joints and allowing it to dry. Consider the hammock, caned seating, and the art of sewing leather and fabrics along seams. Consider the hemp strapping used in Alvar Aalto’s chairs, the woven cane seat pans of the Thonet chairs, or the twisted paper seat pans in Gio Ponti’s cafe chair Superleggera (1951). Sewing and weaving can be significant means of joining and are remarkable in strength, comfort, and aesthetic qualities (Figures 8.16 and 8.17).

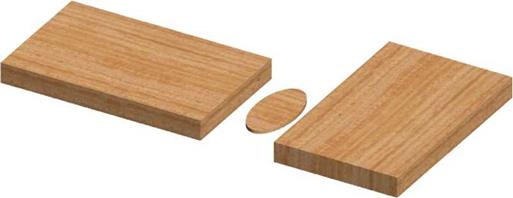

Mechanical fasteners include a variety of wood and metal connectors. The wooden dowel or dowel pin is one way to hold a joint (Figures 8.18 and 8.19). The language of the

|

|

|

|

|

handcrafted wooden pin and through mortise-and-tenon connections drove the aesthetics and language of the Arts and Crafts movement. Finger joints and miter joints are sometimes held in place by a pin connection. Pin connections can also take the form of compressive joints, whereby materials are joined and held together through compressive means. Threaded fasteners are commonly used to hold wood together. Threaded metal insets in wood allow metal-to-metal connections to hold wood pieces together and are better than metal-to-wood connections.

Knock-down furnishings rely on a host of mechanical hardware devices to hold together and easily disassemble individual components. The cam lock, tight joint, and dog bone are devices used to draw wood surfaces together to form one continuous surface. The tight joint and dog bone rely on two recessed cylindrical holes in the wood connected by a recessed channel. The hardware device is then placed in the recessed holes and drawn tight using a threaded bolt and nut, bringing the edge surfaces of the wood pieces together.

Wood Joinery

The way two pieces of wood are joined is very important in furniture design. The expressed joint needs to be strong enough to resist the forces placed on it. This is important because the joint often needs to be the strongest point of the assembly. The following examples of wood joinery illustrate how the joint can be more than a means of joining two pieces of wood together—giving opportunity for the designer to consider the aesthetics of the expressed connection (Figures 8.20 through 8.43).

|

|

|

Figure 8.21 Butt joint. Image by Michael Benkert.

Biscuit connection: A concealed, oblong-shaped, spline joint, typically made of beech wood (Figure 8.20).

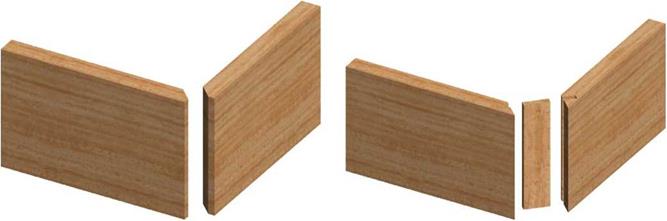

Butt joint: A joint formed by square-edge surfaces (ends, edges, or faces) joined together (Figure 8.21).

Butterfly: A joint used to keep two halves of a board that has already begun to split from splitting further (Figure 8.22). A small piece of wood, in the shape of a butterfly or bow tie, is first cut, and the negative of this shape is cut out of the board. The piece of wood is then placed into the cut hole, keeping the wood and joint together.

Cross-lap: This joint offers exceptional locking strength, more than a full-lap or halflap joint (Figure 8.23).

Dado: A dado cut is a recessed cut made in wood or another material to provide a continuous channel in which another member fits.

A stop-dado cut is a recessed and continuous channel that does not extend through the end face of wood or another material to provide a channel in which another member fits (Figure 8.24).

A through-dado cut is a recessed and continuous channel that extends through the end face of wood or another material to provide a continuous channel in which another member fits (Figure 8.25).

|

|

|

Figure 8.24 Stop-dado. Image by Michael Benkert.

Dovetail: There are three basic types of wood dovetail joints (Figures 8.26 through 8.28).

The through-dovetail consists of both tails and pins and is the negative counterpart on the joining board. The angle of the tail cuts should be 11 to 12 degrees.

The half-blind dovetail exposes only one side of the dovetail joint. Tails should be twice the size of the pins. The dovetail joint is used widely in drawer construction.

|

Figure 8.28 Dovetail-miter joint. Image by Michael Benkert.

The blind miter dovetail is completely concealed within the joint. The interlocking action of the connection makes the dovetail an especially strong joint, particularly in tension.

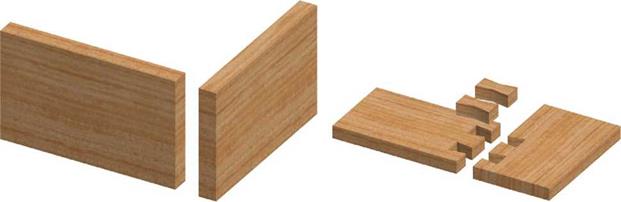

Finger: A joint made by cutting a set of complementary rectangular cuts in two pieces of wood, which are then glued together. Finger joints are similar to interlocking fingers of hands at a 90-degree angle. They are stronger than butt or lap joints (Figure 8.29 and 8.30).

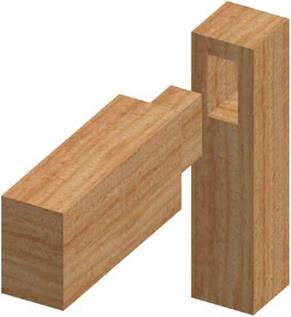

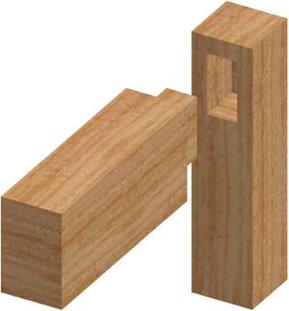

Keyed: Keyed joints are indexed wood connections, in which one piece of wood fits within a prepared slot in the other in order to hold the assembly together (Figure 8.31). Keyed joints are exceptionally strong due to the extended perimeter of the glued surface.

Lap: There are many specific types of lap joints:

A ship-lap joint receives a notch along the entire edge being joined, which increases the stability and surface area for the adhesive (Figure 8.41). Tongue – and-groove joints are commonly used in casework and case goods. One member receives a groove along its entire edge and the other member a matching and interlocking tongue.

Cross-lap joints allow two pieces of material to cross in the same plane. The same amount of wood is removed from each joining member.

|

End-lap joints can be used to extend the length of wood or to change direction. The middle-lap joint occurs at the end of one member and between the ends of the other.

The two pieces should fit snugly but should not be forced.

The two pieces should fit snugly but should not be forced.

In the miter half-lap, the lap is cut at an angle so that the wood members can turn a corner with an angular expression. This joint is often used in making frames (Figure 8.32).

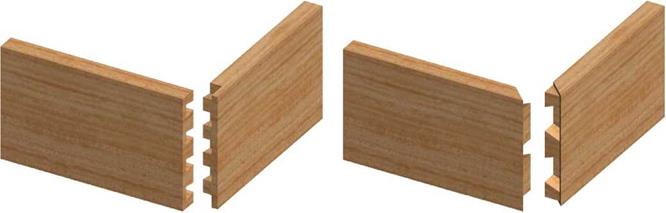

Miter: A miter joint is a type of butt joint where the two members are each cut with equal angles less

than 90 degrees and joined (Figures 8.33 through Figure 8.3, Key joint. mage by Michael Benkert. 8.35). A quirk miter emphasizes the corner of the

joint with a reveal cut into each member along

the joint. A spline is a thin strip of wood inserted into a dado along the miter. In spline construction, the wood members must be thick enough so as not to be weakened by the groove.

Figure 8.33 Miter joint. Image by Michael Benkert.

|

Mortise-and-tenon: In a full mortise-and-tenon joint, the tenon is expressed on the outside face of the mortise member. This type of joinery is one of the oldest and strongest in woodworking. A blind mortise-and-tenon joint conceals the tenon within the mortise member (Figure 8.36). The tenon and remaining wood on either side of the mortise should be of equal strength. A haunch can be added to the tenon to aid in resisting lateral or racking forces. The through mortise-and tenon joint places the joint at the ends of the wood members so that the end grain can be seen (Figure 8.37). A tapered wedge can be used to secure the tenon through the mortise. This type of construction, although it is very sturdy, can be taken apart and reassembled easily.

Pinned, doweled: A joint held together using wooden or metal dowels. The dowels are used to securely position and strengthen the joint (Figure 8.38).

Rabbet: A rabbet joint is fabricated where one or both of the members are recessed on an edge in order to turn a corner (Figure 8.39). In a rabbet joint, one member

|

|

|

|

|

receives a recessed notch along its edge and the other member fits into the recessed notch.

Scarf: A method of joining two members end to end in woodworking or metalworking. The scarf joint is used when the material being joined is not available in the length required. It is an alternative to other joints such as the butt joint and the splice joint and is often favored over these in joinery because it yields a barely visible glue line. Scarf joints are not preferred when strength is required. They often are used in decorative situations, such as the application of trim, molding or fitting of skirting, picture rails, dado rails or chair rails, handrails, and so on (Figure 8.40).

Scarf: A method of joining two members end to end in woodworking or metalworking. The scarf joint is used when the material being joined is not available in the length required. It is an alternative to other joints such as the butt joint and the splice joint and is often favored over these in joinery because it yields a barely visible glue line. Scarf joints are not preferred when strength is required. They often are used in decorative situations, such as the application of trim, molding or fitting of skirting, picture rails, dado rails or chair rails, handrails, and so on (Figure 8.40).

Spline butt: A spline joint relies on an inset piece of wood to hold precisely two pieces of wood together (Figure 8.42). Splines help to strengthen the wood joint and help to precisely guide their alignment.

|

V-groove: A thin beveled line recessed into the face of lumber or small beveled edges where two pieces of wood are joined (Figure 8.43).

![]() Figure 8.43 V-groove, made by butting two chamfered edges together. Image by Michael Benkert.

Figure 8.43 V-groove, made by butting two chamfered edges together. Image by Michael Benkert.