How did modernism affect society? Modernism was not broadly accepted until after World War II, when society began to look to the culture of design for leadership in social change. Exceptionally talented designers worked closely with artisans and craft shops throughout the United States and Europe during this time to bring the modern ideal into popular culture and to create furniture for everyday use. Many designers became prominent within this climate. Their work, working prototypes, and writings inspired a generation of furniture designers and helped develop the spirit of modernism.

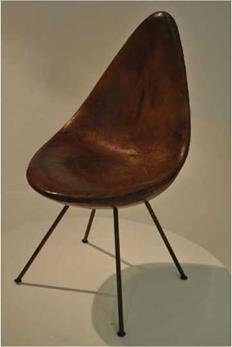

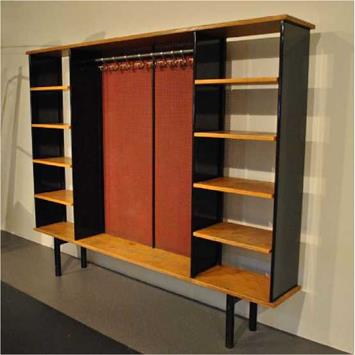

Jean Prouve (1901-1984) was a French designer whose work has been recognized by his ingeniously simple method of fabrication that is typical of his furniture. His furniture design and architecture utilized industrial components and craft-based technologies (see Chapter 4). He was a prolific furniture designer who adopted modern ideas of form and function and was original and exploratory in his use of materials (Figure 10.60).

Carlo Mollino (1905-1973) was an architect based in Turin, Italy. He had a prolific career designing and producing many beautifully crafted and ingeniously structured and curved furnishings. His love of airplanes, car racing, and experimenting with ideas of form and structure is evident in his curvilinear tables. Mollino worked from natural and animal shapes to establish a streamlined series of furniture designs. These pieces evolved from an appreciation of the shapes of Art Nouveau and the work of architect Antoni Gaudi. Mollino’s work was more expressive, and often more sculptural, than that produced in Milan at the time. The changes in his style over the years responded to the evolving technology of bending and working with wood.

|

|

Figure 10.60 Vestiare de cafeteria (changing area for a cafeteria) designed by Jean Prouve (1955). Made with lacquered steel and aluminum panels, hard fiberboard, and ash wood. Photography by Jim Postell, 2011.

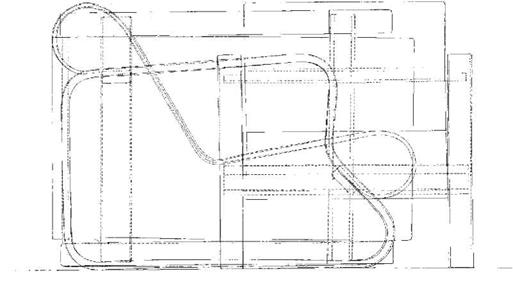

Alvar Aalto (1898-1976) was an architect from Helsinki, Finland. One of the most renowned modern furniture designers, Aalto combined his interest in furniture with his passion for architectural projects. His 1933 three – and four-legged stacking stool, known as Stool 60 (with a back—Stool 65), was designed for his library in Viipuri (see Chapter 4). Aalto’s molded plywood lounge chair, Paimio, (also known as Armchair 41, see Figure 10.61), was designed by Alvar and his wife Aino, specifically for use by tuberculosis patients at the Paimio Sanatorium in 1932. The chair was used in the patient’s lounge, and the angle of its back was designed to help sitters breathe more easily. The arms, legs, and base of the chair are laminated birch wood formed into a pair of closed curved loops, between which is the seat—a thin sheet of 3-mm lacquered plywood, tightly rolled at top and bottom into sinuous scrolls. Resilience is achieved through the scroll-shaped 3-mm thick plywood seat.

|

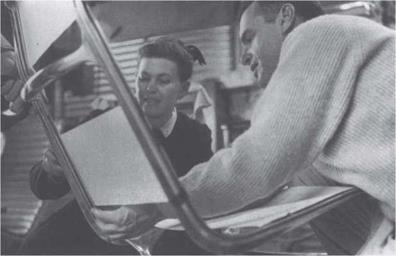

Figure 10.62 Florence Knoll Bassett and Eero Saarinen discussing the base of the Tulip chair (1957). Photography courtesy of Knoll, Inc. |

Later, Alvar and his wife, Aino, formed the Artek Company to fabricate his furniture using a combination of hand finishing and industrial production technologies. His revolutionary use of laminated plywood and Baltic birch captured world interest when his work was exhibited in London, Paris, and New York after World War II.

Eero Saarinen (1910.1961) was a Finnish architect who worked for both Herman Miller and Knoll. He collaborated with his friend Charles Eames on many projects and experimented with plastics, metal, resin-reinforced glass fibers, and upholstery. Saarinen’s work was sculptural, functional, comfortable, and ingeniously fabricated (Figure 10.62). His Tulip chair for Knoll has a molded plastic shell supported by an aluminum base. Many of his chair designs, including the Womb chair with ottoman (1946-1948), are still manufactured today by Knoll.

Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) was a New York City-based freelance designer. His furniture and lighting were characterized by biomorphic form. He designed a beautiful glass-top coffee table with a biomorphic pivoting walnut base, several upholstered sofas, and an array of luminaires.

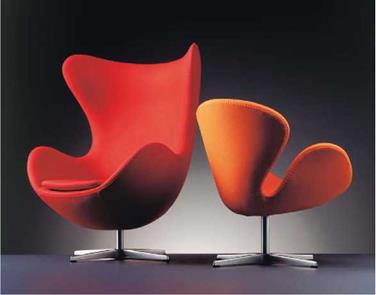

Arne Jacobsen (1902-1971) was a Danish architect and designer whose work built upon Denmark’s modern heritage. In 1950, Jacobsen decided to design furniture as a primary creative activity and began working with the Danish furniture manufacturer Fritz Hansen. The collaboration resulted in the production of the Ant chair (ca. 1951-1952), the Giraffe chair (1955), the Swan chair (1958), and the Egg chair (1958) (Figures 10.63 and 10.64). The Giraffe, Swan, and Egg chairs were specifically designed to complement the public and suites within the SAS Royal Hotel in Copenhagen, Denmark. The Ant chair was one of the first of a series of chairs consisting of a molded plywood shell mounted on three chromed tubular steel legs. Its profile was the characteristic that led to its name. Jacobsen’s lasting vision was of a building, its interior, and the furniture coming together as a complete, harmonious environment.

|

|

||

Hans J. Wegner (1914-2007) was a Danish architect whose chair designs (over 500) are remarkable for their craft, structural integrity, form, and comfort. His work fueled and paralleled a growing interest worldwide in Danish design and helped to foster a unique quality of Scandinavian design, which came to stand for craftsmanship, traditional values, and modern living—all working in harmony. Wegner worked for Arne Jacobsen for five years (1938-1943) and in 1943 opened his own office in Gentofte, Denmark. In 1949, he designed The Chair, which is considered to be one of the classic chairs of the twentieth century (Figure 10.65). The back and armrests, made from teak (or other wood), were incorporated in the design using a single subtle transformative curve. This feature, along with its woven cane seat, encapsulated the spirit of organic Danish modernism.

Charles (1907-1978) and Ray Eames (1912-1988) were a husband-and-wife design partnership. They met at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, in the late 1930s. Charles Eames collaborated on several molded plywood designs with Eero Saarinen that won first prize in a competition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1940. In 1941, Charles and Ray Eames began to develop a system for mass-producing high-quality, low-cost furniture

Charles (1907-1978) and Ray Eames (1912-1988) were a husband-and-wife design partnership. They met at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, in the late 1930s. Charles Eames collaborated on several molded plywood designs with Eero Saarinen that won first prize in a competition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1940. In 1941, Charles and Ray Eames began to develop a system for mass-producing high-quality, low-cost furniture

(Figure 10.66). By 1946, Charles and Ray Eames, as well as Saarinen, were exploring compound curves in sheets of laminated wood, continuing to develop their ideas for the "Organic Furniture Competition," and introduced not only a new look but also a new degree of comfort in their revolutionary designs. After World War II, the Eameses designed a number of chairs and storage units that incorporated a wider range of materials, including fiberglass, wire, and aluminum, many of which are still fabricated today by Herman Miller (Figure 10.67).

In 1956, Ray and Charles Eames completed the Eames Lounge chair, first conceived as a modern updating of the traditional club chair (see Figure 5-37 in Chapter 5). The chair is

|

Figure 10.66 Ray and Charles Eames’s Experimental Lounge chair (1944). Made with molded plywood and steel rod. Photography by Gerald R. Larson, 2011. |

|

Figure 10.67 Ray and Charles Eames working together on the aluminum group desk chair (1958). Photography by Marvin Rand. Courtesy of Eames and Herman Miller, Inc. |

Figure 10.68 Marshmallow chair (love seat), designed by George Nelson and Irving Harper (1954-1956) for Herman Miller. Frame in satin chrome or black painted metal supporting 18 individual cushions covered in fabric, vinyl, or leather. 52 inches wide; 33 inches deep; 32% inches high 16 inches seat height (132 cm wide; 84 cm deep; 82.5 high; 40.5 cm seat height). Image courtesy of Herman Miller, Inc.

multistep assembly made out of molded plywood, rosewood veneer, and down-filled leather upholstery. The Lounge chair, originally inspired by their friend, film director Billy Wilder, has become an icon of American Modernism. The Lounge chair, like George Nelson’s Marshmallow chair, shows each component, from the rubber shocks to the black leather upholstery and at the same time, offers the visceral appeal of repose.

multistep assembly made out of molded plywood, rosewood veneer, and down-filled leather upholstery. The Lounge chair, originally inspired by their friend, film director Billy Wilder, has become an icon of American Modernism. The Lounge chair, like George Nelson’s Marshmallow chair, shows each component, from the rubber shocks to the black leather upholstery and at the same time, offers the visceral appeal of repose.

George Nelson (1908-1986) was an architect who design, and writing about design. His Marshmallow chair was innovative in how the structure and 18 padded cushions were revealed (Figure 10.68). Unfortunately, mass production was not possible because the production process proved too costly, primarily due to the amount of handwork required in the chair’s fabrication. Nelson’s writing about modernist ideas of design and his long-term association with Herman Miller helped to consolidate the movement in American architecture and design, emphasizing how design could be practically applied in both home and office environments from the 1930s to the 1950s.

George Nelson (1908-1986) was an architect who design, and writing about design. His Marshmallow chair was innovative in how the structure and 18 padded cushions were revealed (Figure 10.68). Unfortunately, mass production was not possible because the production process proved too costly, primarily due to the amount of handwork required in the chair’s fabrication. Nelson’s writing about modernist ideas of design and his long-term association with Herman Miller helped to consolidate the movement in American architecture and design, emphasizing how design could be practically applied in both home and office environments from the 1930s to the 1950s.

Harry Bertoia (1915-1978) was born in Udine, Italy, and immigrated to the United States in 1930. He studied at the Cranbrook Academy of Art before setting up its metalworking department. After teaching at Cranbrook and working in California with the Eameses, Bertoia set up his own studio with the help of Knoll and produced the Wire Diamond chair and a series of remarkable wire side chairs (Figure 10.69).

David Pye (1914-1993) was a British master craftsman, a highly educated industrial designer, and professor of Furniture Design at the Royal College of Art in London. His writings and teachings have long been major influences in the fields of woodworking and furniture design. He examined the relationship between design and workmanship. Pye wrote about the workmanship of risk, in which "the quality of the result is not predetermined, but

depends on the judgment, dexterity, and care which the maker exercises as he works."13 Pye contrasts this with the workmanship of certainty, in which "the quality of the result is exactly predetermined. . . always to be found in quantity production, and found in its pure state in full automation."14 One of Pye’s most important ideas is that hand craftsmanship is not always good, and industrialized manufacturing processes are not always bad.

Italian designer Joe Colombo (1930-1971) had a relatively short but productive career designing interior components, furniture, and products. He began his career as a painter and then as an architect. He rapidly moved into interiors and produced his best work by designing functional objects. Utilizing synthetic materials and mass production technologies, he designed a long line of molded plastic furniture pieces. The Universale chair, manufactured by the Italian furniture company. Kartell, was produced in the 1960s. The "Universale" chair was originally designed (1965) to be fabricated out of aluminum. It was produced in acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic and then in polypropylene in 1967. It was the first chair to be injected molded entirely out of one material (Figure 10.70). The height and function of the chair can be changed by removing the detachable legs and replacing them with standard size legs to create a chair for dining, shorter legs for a lower chair for waiting rooms, or taller legs for a higher chair for bar height use. The chair is available in a range of colors and is both lightweight and stackable.

Italian designer Joe Colombo (1930-1971) had a relatively short but productive career designing interior components, furniture, and products. He began his career as a painter and then as an architect. He rapidly moved into interiors and produced his best work by designing functional objects. Utilizing synthetic materials and mass production technologies, he designed a long line of molded plastic furniture pieces. The Universale chair, manufactured by the Italian furniture company. Kartell, was produced in the 1960s. The "Universale" chair was originally designed (1965) to be fabricated out of aluminum. It was produced in acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic and then in polypropylene in 1967. It was the first chair to be injected molded entirely out of one material (Figure 10.70). The height and function of the chair can be changed by removing the detachable legs and replacing them with standard size legs to create a chair for dining, shorter legs for a lower chair for waiting rooms, or taller legs for a higher chair for bar height use. The chair is available in a range of colors and is both lightweight and stackable.