All across Europe during the nineteenth century, cities began to host large expositions to showcase innovative cultural ideas, designs, and inventions. Munich, Germany, held its first annual exhibition in 1818, and subsequently Metz and Vienna, Austria, and Oporto, Italy, held exhibitions as well. These exhibitions showcased international culture, including influences from Turkey, China, and Japan, and had great social and economic impact upon the culture of design. The Great Exhibition, the first recognized international exhibition, was held in 1851 at Hyde Park, London, in Joseph Paxton’s recently completed Crystal Palace. This building was a monumental undertaking of modular building, utilizing prefabricated glass and iron components. The technology employed in its construction was similar to that used in the prefabricated furniture produced during the Industrial Revolution.

From an exhibition, a style that was promoted and admired would be rapidly disseminated to all parts of the world by the press. With the world watching and encouraging new furniture designs, a complex eclecticism emerged, due in part to the improvements in industrial production, transportation, and communication.

In this new industrial era, museums began to be established. The new development in society helped to catalog ideas and styles from antiquity. The South Kensington Museum in London was famous for both the study and design of the decorative arts, serving as both a museum and a home for several international exhibitions. Today, it is the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In this new industrial era, museums began to be established. The new development in society helped to catalog ideas and styles from antiquity. The South Kensington Museum in London was famous for both the study and design of the decorative arts, serving as both a museum and a home for several international exhibitions. Today, it is the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Around 1830, the craftsman Michael Thonet began making chairs by bending presteamed beech wood. These chairs became the forerunners of the bentwood furniture that made the company GebrQder Thonet world famous. In 1851, GebrQder Thonet of Boppard-am-Rhine, Germany exhibited bentwood furniture in London at the Great Exhibition. By 1900, the Thonet Company employed 5,000 workers producing 4,000 pieces a day, with another 25,000 people employed throughout Austria producing bentwood furniture. These pieces were of great inspiration to industrial production methods and influenced the rise of the Modern Movement (Figure 10.42).

GebrQder Thonet exported modular, prefabricated, and unassembled bentwood furniture in kit form all over the world. This was the first documented case of a company producing knockdown pieces that provided a cost-effective means to distribute furniture to a global clientele. Originally conceived of and fabricated as laminated wood furnishings, bentwood technology came about because the laminated furniture tended to delaminate during the long ocean journeys to distribution ports throughout the world.

The Industrial Revolution 337

By the later nineteenth century, machines were assisting in the carving and cutting of wood. Machines were limited in their dexterity and other abilities, and machine carving had to be finished by hand. Therefore, furniture was relatively expensive to manufacture, but now multiple pieces could be inventoried. At the turn of the twentieth century, furniture was made with both machines and hand tools—calling into question traditional paradigms of fabrication and the dependency on craftsmanship.

During the nineteenth century, machine technology varied greatly by country and region. German cabinetmakers were fine technicians and were considered to be the best at their craft; some of them moved to Paris, the economic and cultural center for furniture design at the time. This assembly of talent in one large European center resulted in a melting pot of styles and growing eclecticism. This, in turn, helped to break down the sense of regionalism in design and fabrication and set the stage for the International Style that would emerge in Germany later in the twentieth century.

As the nineteenth century progressed, attention to handwork declined. Moreover, as labor costs continued to rise, the quality of workmanship decreased, especially after the First World War. In addition, the quality of timber declined, due in part, to kiln-drying technology. The rapid reduction of the water content in freshly harvested lumber stressed the lumber, causing warping and bowing to occur more frequently. With a poorer stock of raw material and the expanding use of new technology, craftsmanship became less important. This negatively impacted traditionally designed and fabricated works, indirectly affecting the guilds and divisions between the trades.

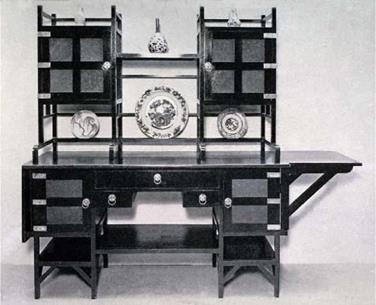

With the ability to refine hardware and details using a greater variety of metals, the use of brass hardware became widespread in the third quarter of the nineteenth century. Inventive hardware and mechanically operated connections resulted in a new generation of mechanically transformative pieces. Mechanical furniture resulted from various patented inventions. Furniture such as the In-a-Dor Murphy bed or fold-down bed became popular space savers, finding their way into small apartments and sleeping cars in trains.

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, international exhibitions became forums for introducing innovation. The exhibitions were important cultural and economic events, exhibiting the "newest and the best" to a growing audience. However, in reality, the wealthy and the ruling class financed most of the exhibits. Significantly, their rise occurred in tandem with the Industrial Revolution, bringing new industrial materials, production methods, and mechanical types to the public. The Paris Exposition Universelle, first occurring in 1855, was organized to occur at 11-year intervals. The Paris Exhibition of 1900 marked design innovations leading into a new age. Following exhibits reinforced the age of mechanization, as seen in the Saint Louis exhibition in 1904, the Paris Art Deco exhibition in 1925, the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, and the 1939 World’s Fair in New York City.

Technology enabled the production of nearly every kind of furniture. Eclectic works emerged, and with them a growing disconnect between the way something was fabricated and what it looked like, pushing design and production further apart.

The Industrial Revolution had a far-reaching impact on all aspects of society. Railroads allowed raw timber and completed furniture pieces to be transported long distances. This was the time when large numbers of books and periodicals were published. Books such as Henry Shaw’s Specimens of Ancient Furniture (1836) presented drawings of early furniture pieces. Richard Bridgen’s Furniture with Candelabra and Interior Decoration (1838) was also influential. Books that illustrated older styles helped rekindle a return to earlier forms and a revival of previous styles.

|