The Renaissance

An emerging Renaissance had begun in Europe by the early fifteenth century. The rebirth is often cited to have originated in Florence, marking Filippo Brunelleschi’s (1377-1446) completion of the dome for the cathedral in 1420 (Figure 10.20). Science, engineering, mathematics, human anatomy, perspective drawing, and new materials fueled a rebirth in the arts, furniture design, and architecture. The artist began to be admired as an inspired creator, which serves to mark the birth of the designer as understood today.

Craft guilds dominated the workshops during the Renaissance. Instead of igniting scientific and artistic revolution, they restricted exploration and experimentation in design. A joiner was not allowed to inlay. Engravers were not allowed to do carpentry. Designers did not fabricate. Craftsmen had to satisfy their guild and did not venture beyond their prescribed division of labor. The segregation of skills generated excellence in workmanship within specific trades but significantly limited creative exploration. The Renaissance marked the beginning of an important division between "hand" and "head," between art and science, and between craft and theory. It was a time in the history of furniture design when specialization and division of labor prevailed. Furniture produced during this period had carvings and scrollwork, and was often made from walnut.

Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) was a renowned architect and architectural writer who embodied the Renaissance in his built work and written treaties. He established principles that defined beauty as "the harmony and concord of all the parts achieved in such a manner that nothing could be added or taken away or altered except for the worse."5 Ornament, according to Alberti, "gave brightness and improvement" to the works. He inspired many furniture makers to incorporate decorative motifs into furniture using proportional systems and a classical repertoire. Alberti had strong ideas about architecture, art, and design, though his ideas were not new. He adopted ideas from the famous Roman writings of Vitruvius and Aristotle. Alberti’s success as an architect and his influence as a writer illustrate how significant the dissemination of historical knowledge can be.

|

|

Social distinctions were important during the Renaissance. Many furnishings were designed to express social status. Particular pieces included the armoire, bed, buffet, cradle, and marriage chest. For royal events and important social or political ceremonies, furniture was useful to denote class and rank. The canopy bed (Figure 10.21) recalled the canopy thrones used by kings. It extended beyond the need to create privacy and warmth for the sleeper. The canopy’s material, size, and design expressed social status.

|

|

Figure 10.23 Credence table, chapel, Sisters of Mercy, Belmont, North Carolina. Photography by Jim Postell, 2002.

The cassone was a chest. It could be made small for storing jewelry, used for storage while traveling, or made large to serve as a wedding or dowry chest. Traditional marriage chests were carved, gessoed, gilded, or painted to tell a story about the families of the couple being wed (Figure 10.22). They were typically produced in sets of two. One was fabricated for the bride and the other for the groom. They were quintessentially mobile, traveling with the bride and groom to establish their new home. These dowry chests became principal interior furnishings that contained the bride’s dowry and the couple’s personal possessions and were displayed prominently in the home. This tradition was carried into the twentieth century as a hope chest to store household textiles and items, but it became more of a repository for symbolic or decorative memorabilia.

The credenza found its way to the home from a religious environment, then back again. The credenza is a sideboard, often draped in cloth to assist in dining, but it is related to the contemporary liturgical Catholic credence table, which is a small table located near the altar upon which the communion meal is placed before mass (Figure 10.23). Both terms share the Latin root credere, meaning "to believe."

|

|

During the 1400s, X-shaped folding chairs were popular for an informal and relaxed posture. In response to a growing desire for a more relaxed posture for the wealthy, two seating types emerged. The first was the lit de repos, a daybed with a raised back for daytime reclining. The second was a small, armless stool-like chair called the sgabello. The sgabello was a light, three or four-legged wooden chair used primarily for dining.

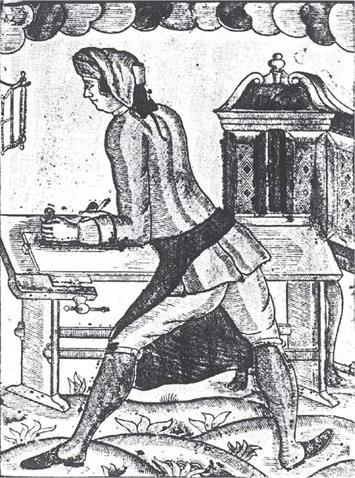

By 1500, the Italian Renaissance had a significant impact on European art and design, especially among German artists. Albrecht DQrer visited Italy from Nuremberg and Augsburg. His prints and engravings helped to popularize Roman classicism in Central Europe. An emerging demand for classical furnishings generated an organization among craftspeople to legislate both the design and fabrication of classical pieces. The growing legislation resulted in a network of craft guilds throughout Europe. These guilds controlled the standards of quality in the fabrication of furniture (Figure 10.24).

Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch seafaring expeditions resulted in the import of exotic materials. As a result of Dutch trade with the Far East and West Indies, ebony became available in limited supply to decorate plain oak furniture. Because ebony is an exceptionally strong wood, thinner members could be used, making it an excellent choice for inlay work and veneering.

Walnut was abundant in southwestern Europe and a source of export for France and Spain. The increased availability of walnut provided carvers with greater opportunities to depict elaborate forms in furniture, built-ins, casework, and case goods.

During and following the Renaissance, published treatises and pattern books became popular throughout Europe due to the invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century and the prevalent use of woodcuts. Eight books by the Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554) were translated into English, French, and German. The illustrations in his architectural treatises about proportion and geometry had a significant influence on architects, designers, and fabricators throughout Europe. The French designer Androuet du Cerceau (15201584) published furniture engravings that influenced the use of carving in major European centers. In 1550, du Cerceau presented objects with classical ideas of proportion that were overlaid with geometric patterns and representations of human and animal figures. Hughes Sambin (1520-1601), an architect, wood carver, and furniture maker, published a book on the diversity of the figures used in architecture. Sambin’s book inspired figural representation, not only on many sculptural pieces of furniture, but also in the development of carving in low and high relief.

During and following the Renaissance, published treatises and pattern books became popular throughout Europe due to the invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century and the prevalent use of woodcuts. Eight books by the Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio (1475-1554) were translated into English, French, and German. The illustrations in his architectural treatises about proportion and geometry had a significant influence on architects, designers, and fabricators throughout Europe. The French designer Androuet du Cerceau (15201584) published furniture engravings that influenced the use of carving in major European centers. In 1550, du Cerceau presented objects with classical ideas of proportion that were overlaid with geometric patterns and representations of human and animal figures. Hughes Sambin (1520-1601), an architect, wood carver, and furniture maker, published a book on the diversity of the figures used in architecture. Sambin’s book inspired figural representation, not only on many sculptural pieces of furniture, but also in the development of carving in low and high relief.

Craftsmen drew inspiration from Lorenz Stor’s Geometria et Perspective (1567). This publication contained images of geometric forms intended to serve as perspective studies specifically for craftsmen working in wood, showing images of formal studies juxtaposed against a background of classical ruins.

With an increase in the number and type of articles of clothing that an affluent person wore, the dresser and armoire became significant furniture types in France and Italy around 1550. The armoire was larger than the dresser and was a precursor to the wardrobe closet (Figure 10.25). Related to both the dresser and armoire was the cupboard, a paneled box, either freestanding or wall mounted, for storing equipment and food used in dining. These large furnishings caused fabricators to rely on more traditional carpentry skills, and this evolution generated further specialization and division of labor within the French, Italian, and German furniture centers. During this time, furniture companies began to emerge as a new industry. Through the resources available to a furniture company, guilds could work together in one organization to produce a variety of furniture.

The movable table with elaborate supports, connected by stretchers and typically covered with a carpet, became a popular furniture type in the sixteenth century. Movable and transformable tables and chairs (i. e., the gateleg table and the chair-table) responded to the desire for flexibility in social and utilitarian function. This worked well in domestic settings, where houses were still quite small and rooms had multiple functions.

Antwerp, Belgium, was a center for the making of veneered and painted cabinets. These cabinets were worked in ebony or ebony veneer, with painters specializing in depicting mythological or classical scenes. Surrounding cities such as Amsterdam and Brussels followed Antwerp’s lead in producing painted and veneered furniture.

Textiles were used to cover Dutch tables during this period and became one of the chief forms of social and class display. As a result, textiles were prominently used within residential and commercial interior spaces as tapestry wall hangings, and as area rugs. Amsterdam

was becoming a furniture-making center in tandem with its emerging political and growing economic base during the fifteenth century. This generated a prolonged focus on textiles incorporated in furniture design, which eventually led to the development of upholstered pieces in the eighteenth century.

was becoming a furniture-making center in tandem with its emerging political and growing economic base during the fifteenth century. This generated a prolonged focus on textiles incorporated in furniture design, which eventually led to the development of upholstered pieces in the eighteenth century.

By the end of the fifteenth century, Spain and Portugal had become wealthy countries. The Moors, who had conquered Spain in the eighth century (and lived there for over 700 years), were expelled in 1492. Although the Renaissance influenced Spain, the Moorish influence resulted in the distinctive Spanish style that used geometric systems, including ad quadratum (of the square), and pronounced visual contrasts in materials.

The gold and silver taken back to Spain and Portugal from Mexico and Peru were incorporated into furniture. With its superior fleet, Spain enjoyed trade with the Orient, which brought new lacquer finishes and frontal approaches to furniture design. A frontal approach is a formally arranged composition intended to be experienced straight on. Liberal use of decorative wrought iron characterized many pieces. Chair legs and arms were often turned and scrolled. The Spanish scroll foot was distinctive, as were the decorative nail heads shaped into roses and shells in various furnishings.

During the sixteenth century, the Spanish developed the idea that side tables and cabinets on stands, as well as chairs, should be used in specific positions within a room to define the architectural space. This spatial concept was central to the design and function of

European Baroque furniture, which developed in France during the reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715).

In the sixteenth century, the fall-front cabinet (writing desk) developed into a popular type of furniture known by the Spanish name varguetu (Figure 10.26). The exterior front piece was usually elaborately carved, with exposed metal hinges. The interior was organized with drawers and compartments for papers, writing equipment, and valuables. Upholstery and finely tooled leather were applied to many chairs and tables. Lisbon, Portugal, emerged as an active center for furniture makers.

In 1580, Phillip II unified Spain and Portugal. Because Spain ruled Mexico at the time, furniture makers in Mexico, like those practicing in Toledo or Lisbon, were required to be able to make a vargueno, an inlaid hip-joint chair, and a turned bed and table. Trade regulations forbade craftsmen to open a shop in the city without first being examined in their trade.

In England, joiners became recognized as the chief furniture makers during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. But even within the joiners’ guild, there were conflicts due in part to new fabrication techniques brought to England by the Flemish. Board construction began to replace panel-set-in-frame fabrication.

In the second half of the sixteenth century, many furniture makers developed framed-panel joinery, known as rail and stile construction, held together by pegs. The perfection of the miter joint greatly simplified the manufacturing of molded frames. Furnishings became lighter and more mobile.

In the seventeenth century, guilds began to evolve into training centers. They were active in governing the workmanship and behavior of members and in regulating the price and quality of

manufactured goods. However, despite the power and strength attained in the early sixteenth century, guilds began to lose power due to their economic dependence on the Catholic church. By the end of the eighteenth century, the Reformation and the dissolution of the monasteries resulted in political and societal shifts that limited the production of high-end furniture.

Nonetheless, craftsmen continued to work throughout Europe. As markets expanded, a new, rising middle class of English merchants and tradesmen reorganized themselves and received new charters, first from Queen Elizabeth I and later from King James I. Slowly, furniture companies began to emerge as early as 1570 with a dominance of joiners.