1720-1740

The Artificers in this Place Exceed Ary upon ye Continent And are here also Most Numerous as Cabinet Makers, Chacc A Coach Makers. „ . ’Watchmakers. Printers, Smiths, &C.1

|

I |

N 1750 James Bilker, a traveller from the West Indies, found Boston filled with craftsmen. To him, their number surpasscxl that in any other American town. Today, as one passes through museums and historical societies, he is likely to agree with Birket. Hundreds, if not thousands, of pieces of furniture made in the Boston area during the eighteenth century have survived. Their makers are, for the most part, unknown. However, the quantity of objects attests to tlic activity of many craftsmen. This paper is concerned with these men—their number, their opportunities for work, their homes, and the economy in which they operated. Such information provides new insights into not only the men themselves but also their furniture.

Between 1725 and 1760 approximately 127 joiners and cabinetmakers,2 chairmakers, 23 upholsterers, 16 carvers, 11 turners, and 9 japanners worked in Boston. These 224 craftsmen comprised a total larger than that of any other American town during this period.

1, Ірин1 CufiUfy Rnndfb M*it by Janas Birket rrr hit Voyage la North America 1?}C – r7jf, <лЗ. Chillis M. Andrew 1 (New Haven, 1916), p. 24.

1. In ihis piper nodiitisctfce is nude bn ween joiners known 10 hive nude furniture and cabinet makers. For more information <xi the use of the two terms in colonial Boston, see Bcnno M. Formin, "Urbin Aspect» of Massachusetts Furniture in the Lite Seventeenth (Гсп Гигу," IVinlerthur Conference Report Country Cabinetwork tmJ Simple City Furniture [Chirlottwville. Virginia, l57e], pp. 17-Ю,

Philadelphia, Boston’s nearest competitor, contained about thirty percent fewer craftsmen.[2]

An increase in shipbuilding during the early eighteenth century provided abundant work for many of these craftsmen. Queen Anne’s War {1702-1713) had proved especially profitable for local merchants,[3] Their desire to enlarge the home fleet and the willingness of foreign entrepreneurs to purchase Boston vessels created jobs in every branch of the furniture industry. For example, Samuel Grant, an upholsterer, often supplied chairs and stools for the cabins of newly constructed ships.[4] Joseph Ingraham, a local carver, completed the carved details for five ships during 1739, His bill of over £300 included ^зо:^:о for an “11 foot Lyon for ship Dragon.’’[5] Such accounts are typical for carvers and suggest that they were far busier with shipwork than with furniture. Joiners often outfitted the interiors of vessels. Two such craftsmen, Daniel and Joseph Ballard, were often involved in civil litigation and were forced by die courts to account for their work. According to one law suit, Joseph Ballard constructed panelling, cupboards, chests, lockers, cornice moldings, window sashes, and “ye hen & goose coop" for a ship,[6] [7] Other joiners provided similar services, sometimes building tables and desks in addition to performing finished carpentry work,®

Besides shipwork, merchants offered cabinetmakers and ehairmak – ers the opportunity to export their goods in vessels bound for Nova

Scotia, the coastal ports of New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, or the West Indies. That craftsmen took advantage of the mercantile activity is demonstrated by the statements ot Plunkett rlecson, a Philadelphia upholsterer. In 174г be advertised chairs "cheaper than any made here, or imported from Boston." Evidently, hundreds of Boston chairs were Hooding into the area because two years later Flceson chastised "the Master Chair Makers in this City. . , Jfor] Encouraging the Importation of Boston Chairs,"9 Even in (76г, when Philadelphia cabinetmakers were beginning to produce their finest furniture, ЕЬспсйсг Call asked his brother in Boston to have chairs made by a Mr, Lampson and shipped to Philadelphia.10

hi addition to ship con struct ton and an export trade, the merchants themselves were excellent clientele for craftsmen. Though occasionally importing furniture from England, local merchants usually relied on Bostonians for their home furnishings. Samuel Abbot, who began his mercantile career in 1760, kept an "Accompt of Household furniture."11 in it he noted the purchase of his household goods for the next thirty years. With the exception of four Philadelphia (Windsor) chairs12 and two looking glasses, all of Abbot’s furniture was made in Boston. Chairmakcrs Henry Perkins, William Fullerton, and George Bright provided mahogany tables and chair frames. John Forsyth, William Gray, and Ziphion Thayer upholstered these chairs and furnished bed mattresses, pillows, curtains, and window cushions. Ad і no Paddock, a coach maker, billed Abbot £40 for a chaise "Carved Gilt & Laced”,J while John Gore, a successful jipanncr, [8] [9] [10] [11] [12]

TheTOWN of

TheTOWN of

15 О S T О N

опт

P°*KUI

I’uWiLtirl In uXr

|

tYil* ршм^-і ■|rLii M-1 .’j™ IL Л/^И f* Objiuti |

|

41 ‘/* tyti Lyrt /<уи |

|

|

Com mos

|

|

|

|

|

painted Hid framed a coat of arms for ^2. Such complete documentation is nonexistent for the first half of the eighteenth century. However, individual references to purchases by Darnel Henchman, Matthew bond, and other merchants suggest thaL they, too, primarily patromacd local craftsmen.1,1

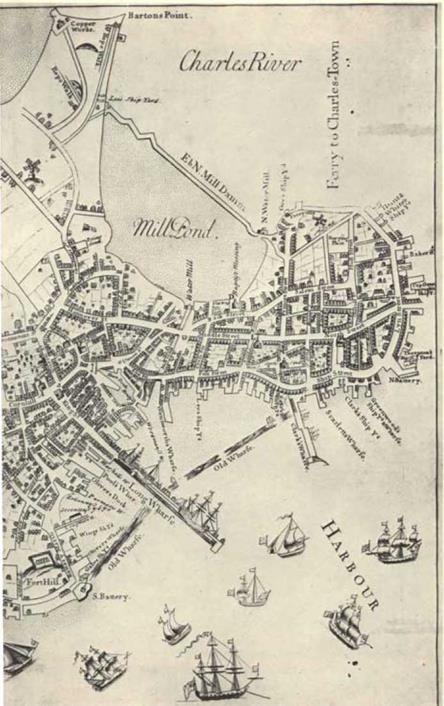

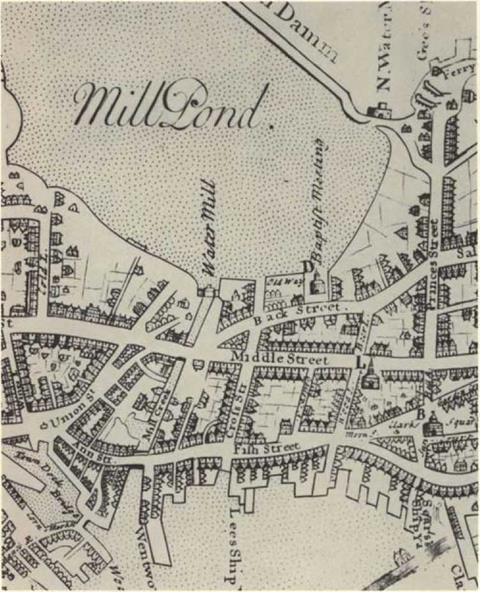

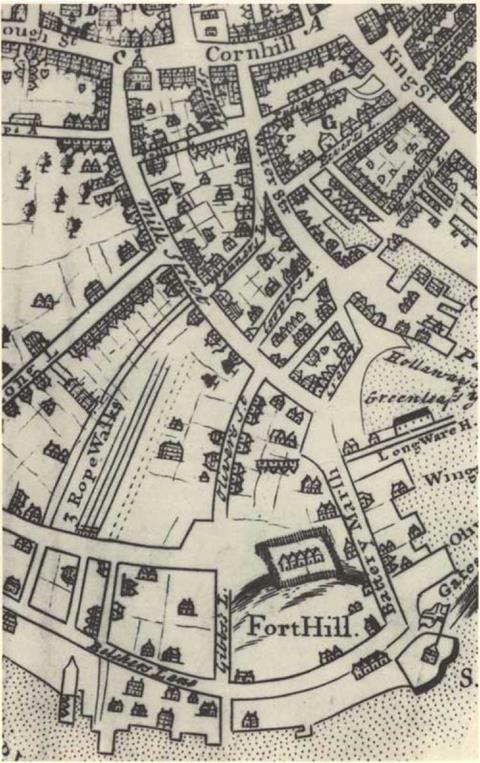

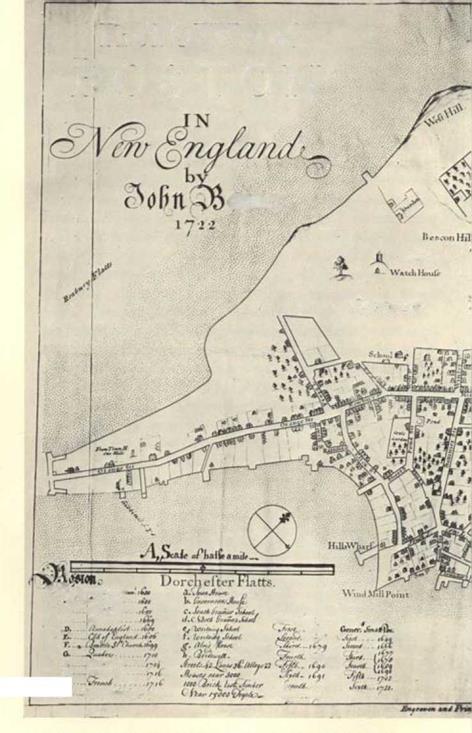

The homes of furniture craftsmen were located throughout the city. Samuel Wheeler, a chair maker, lived on Orange Street1 s near the neck of land leading to Roxbury. Thomas Luck is, a carver, owned a portion of a home almost two miles away on Lynn Street in the North End (fig, H), Many lived in craftsmen’s districts either in the North End between Union and Prince Streets or in die South End between Combill and Battery March (figs. 9 and 10}.John Brocas, John Corser, Samuel Ridgway, and Job Coit resided on Anne and Union Streets. A block away on Back and Middle Streets were the homes of cabinetmakers Nathaniel Holmes, Thomas Sherburne, Janies McMillian, Thomas Johnson, and William Johnson. In the South End on Battery March lived at least five chairinakers. Occasionally these individuals owned their dwellings, but as the century progressed more and more men chose to rent houses, portions of tenements, or just rooms, indeed, evidence suggests that middle-class property-owning craftsmen of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries were gradually replaced by increasingly wealthy merchant-craftsmen and poor journeymen. w

Boston furniture makers worked in an economy based on commodity and credit exchange. Foreign coin did nor circulate in the city and even the paper money printed by the Massachusetts government was scarce among craftsmen. As a result, a type of bartering [13]

|

|

system prevailed where workmen traded small amounts of cash, goods, services, and notes of obligation in lieu of money. A note written by ‘William Handle, a japanner, is typical of die la tier form of exchange. On July 15, 1724. he promised to pay "Mr John Greenwood or order Fourty five Pounds on or before the first day of April next, it being for Sundry Prints of ye Ciry of New York Bought A’ Received of him."11

in this economy, personal trust played an important role. No man wanted to sell goods to another unless he believed that he would eventually be repaid. Artisans especially needed good credit reputations because of ibe many items required in their work. Cabinetmakers turned to merchants and ship captains for imported lumber and to braziers and shopkeepers for imported brass ware, tools, nails, and glue. Furthermore, in an urban environment, they depended on victuallers and innholders for food and drink. To succeed in such an atmosphere required hard work and reliable connections within the craft and the community. Apprenticeship and kinship ties were the easiest ways of securing these connections, in both, masters and fathers provided assistance for younger men to begin their careers. For tJiis reason, successive generations of families followed the same trade and became trusted members of the community. The Coit family, comprised ofjob. Sr., and his three sons, worked as cabinetmakers. The Perkins family included five chair makers in two general ions. The most extended family, the Froth inghams of Boston and Charlestown, contained sixteen woodworkers in four generations.1® Some craftsmen married into the families of furniture makers. F-benezer Clough, a Boston joiner, married Hlizabeth Welch, the daughter of a Charlestown joiner, Robert Davis, a Boston japanner, married the daughter of William Randle, another local japanner.

These complex kinship tics may have contributed to the general conservatism of Boston furniture when compared to that of Iі hi la – [14] [15]

delphii, The prolonged use of stretchers or the continued appearance of Queen Amic style furniture iti die lyfios and 1770s could have resulted from tradition a! family training.

Family tics not only provided security for Bostonians who trained locally as apprentices, but also made it extremely difficult for immigrants to break into the furniture industry. Between 1730 and 1760 no inventory of an immigrant craftsman exceeded /hoo while those of several native workmen surpassed ^20ООг|,( Family connections by no means insured success, but they seem to have been at least a prerequisite for the attainment of wealdi in the furniture industry.

Boston’s faltering economy after 1740 further decreased the immigrants’ opportunities, A drop in population during the thirty years prior to the Revolution reflected the deteriorating condition. As the Reverend Andrew Burnaby stated in 1760. “The province of Massachusetts-Bay has been for some years past, l believe, rather on the decline. Its inhabitants have lost several branches of trade, which they are not likely to recover again,”50 Growing competition from other coastal ports, the Molasses Act. and high local taxes created little need or attraction for additional craftsmen.

The best example of the immigrant craftsman’s problems is Charles Warham. Bom in London in 1701,11 he travelled to Boston sometime before 1724.22 The young cabinetmaker, who had apparently completed an English apprenticeship, discovered hard times in his new home. Numerous court cases reveal that he was unable to pay [16] [17] [18] [19]

for food or rent.23 Withour any means of solving bis dilemma, War – ham evidently became a poor risk to his creditors. In )731, he sold his household possessions and moved to Charleston, South Carolina,24 On November 2, 1734, he advertised in the StWi Catalina Gazette "all sorts of Tables, Chests, Chests-of-drawers, Desks, Bookcases &e. As also Coffins of the newest fashion, never as yet made in Charles – towti,"15 He purchased lots for his home and shop on Tradd Street and during the ensuing years established a prominent cabinccmaking trade in Charleston. Asa result of his newfound prosperity, he turned later in life to land speculation, In 1776, for example, he offered for sale 5000 acres of South Carolina real estate. He died on July 20,1779. leaving a substantial estate.26 Debt-ridden in Boston, a city glutted with craftsmen, Warliam succeeded in Charleston where demand for his work was far greater.

Jn contrast to this immigrant, several of Boston’s native sons prospered in die furniture industry. The career of Nathaniel Holmes, a cabinetmaker, is illustrative of how men with strong local kinship tics manipulated the credit economy to their best advantage. Holmes was born in Boston on December 29, 1703.22 His father, Nathaniel, Sr., had worked as a joiner and mason during the late seventeenth century. Young Nathaniel was only eight when his father died, and presumably his mother apprenticed him a few years later to one of Boston or Charlcstosvn’s many cabinetmakers. By 1725 he had opened his own cabinet shop near die Mill Bridge in Boston.28 Three years later he married Mary Webber, the daughter of a lumber dealer and sawmill owner, a connection which obviously served his best interests, and during the next decade expanded his cabinetmakmg business by employing workmen from the Massachusetts Bay area.

In 1733 Holmes purchased a distillery on Back Street and for five

a;. Ibid., Mjieh as. 17J1, Augiui 28, 173a,

24. Ibid., March j, 1733.

25. Quoted jn Burton, Charlatan, p. lib.

іЛ. Ibid,, pp, iafl-127.

27. For information jHToininu to Holmcj’i life, see George Arthur Gray, Tkt DfUtntlontt of Grorgr Иоїта ofRoxbury tMf-{Важчі. 190*), pp. id, iK-JO,

5ft MUfdhintoui Papas, p, 113,

years prospered through the production of both rum and furniture. At the same time he began to hire vessels to carry his goods up and down the coast. His rum business and carrying trade proved so profitable that after 1740 he abandoned his cabinetmaking operation. To complement his distillery’. Holmes built a sugar baking house in 174s29 and for the next twenty years shipped sugar, molasses, and rum 011 his own sloops and schooners to Newfoundland, the Middle Colonies, and the South. When he died in 1774, he left an estate valued at almost 4000 which included land and houses throughout Massachusetts and Maine. He owned dwellings on Back, Charter, Middle, and School Streets in Boston as well as a farm in Malden and land in Falmouth and Kcnnebeck.30 Holmes succeeded far better than any other cabinetmaker in Boston, His biography indicates that a craftsman could become wealthy, bur only by changing occupations could he amass a great fortune.

Fortunately, surviving documentation permits a detailed analysis of Holmes’s furniture business.31 During the 1730s Holmes served as a merchant-middleman for numerous craftsmen in Boston and surrounding towns whom he supplied with food, clothing, brass ware, lumber, and glue. In return, they constructed furniture which they delivered to Holmes who then sold it to ship captains for export or to private customers in Boston.

Holmes employed ten joiners and cabinetmakers, only four of whom worked in Boston. Robert Lord, Richard Woodward, and Thomas Johnson lived Ш Boston. Woodward, m fact, boarded w’ith Holmes. Another local cabinetmaker, Thomas Sherburne, helped Holmes manage the business in 1736 and 1737, John Mudge and Jacob Burdit resided in Malden, a small village oil the Malden River,

29. Thomas Aikim it> Njtlujud Holmes, Boston, vni, Bilk March 16. 174#. Bourn Papers (Baker Library, Harvard University),

30. The inventory mulled Suffolk County Registry of Probate, Bos

ton, Massachusetts, docket 157×7 (hereafter Suffolk Probate Records).

Jl. The fulleuinj; information is based tin iccoiims between Holmes aild John Mtidgr, Jacob Burdit, and Mary J л к son, SS. srj-.si3, §.7*4.1 (Winterthur Libraries, Joseph Downs Manuscript Collet ti>m) and two folders of bills and receipts in rhe Bourn Papers, vr. Accounts Current 1717-17:5 8, and Vltt. Bills 17×8-1759 [Вдкег Library, Harvard University).

north of Boston. Thomas and Chapman Waldron lived in Marblehead, a coastal settlement about sixteen miles northeast of Boston, James Hove у worked for Holmes for nine months in either Plymouth or Boston. The home of Timothy Gooding, Jr., the last of I folmes’s workmen, has not been located. The majority of these men were between twenty-one and twenty-eight years of age,32 suggesting that Holmes was responsible for aiding them at the start of their careers, when they needed credit to purchase household and shop goods.

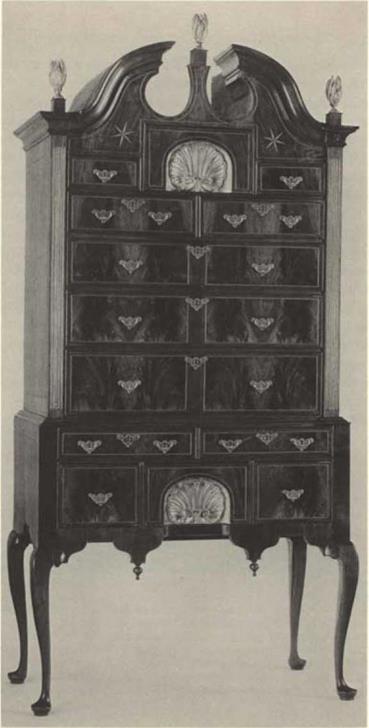

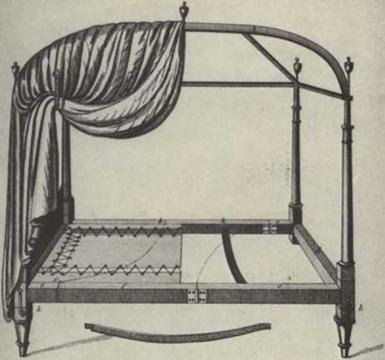

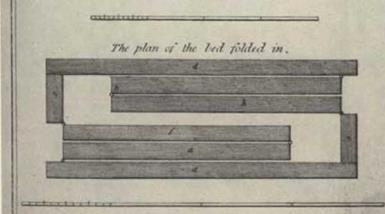

Holmes dealt with three turners, two bed bottom makers, and з japanner, all presumably of Boston. The turners, John Underw ood, Daniel McKillister, and Daniel Swan, produced lathe-turned legs, drops, finiaIs (called Haines in the accounts), pillars, and balls which were later used by die joiners to cm hellish their furniture. Pillars and balls were produced in sets and probably used in the upper portion of tall ease clocks as columns and fi trials, respectively (fig. 11). The bed bottom makers, William Buifmch and Elias Thomas, laced canvas to bed frames made by Holmes or his workmen. A typical cloth bottom is і Lustra ted in The Cabinet Dictionary by Thomas Sheraton (fig, 12),33 Holmes’s japanner, William Randle, performed ail assortment of services, including the gilding ot pillars for a clock and the japanning of a pedimented high chest.

The personal papers of Nathaniel Holmes reveal that these fifteen craftsmen constructed 338 pieces of furniture for their employer between 1733 and 173р. Unfortunately, only a portion of the business is documented in the bills and receipts. We have no information, for instance, 011 how much furniture Holmes constructed himself. Nor do we have complete accounts for each craftsman’s work. The total number of objects probably far exceeded those recorded in the papers.

Jl. Birth ґягикії hive imly been found for Johnson, Mudjie, Uurdil. and Shct – bunie, jII ot’ whom were burn after 170S. Woodward wu called Holmes’s apprentice in t7jd ind інші have been in his nily twenties when hired by his former muter. Jeremiah Townsend m Nathaniel Holmes, Bunion, vi. Accounts Current, February i. 173V. Bourn Варт (Baker Library, Harvard UnivrrsiiyJ.

}J. Thomas Shetatun, T7ir Cahinrl Dictionary (Loudon, lSd]), plale XV.

11. Detail or Tall Clock Showing Pil – larsandB alls. Works by Ec njarnin Bsgnill, Boston, C, 1715-17JO – Case, walnut and white pine; и. 98Ул inches. w, inches. s. 10а/» indies. (Collection of Mn, Charles L, Bybee and tlie late Chides L. By bee: photo. Richard Cheek.) For an overall view of tlie clock, lee /Jrrfi^uer, ХС1ГІ (January, 1908), 77.

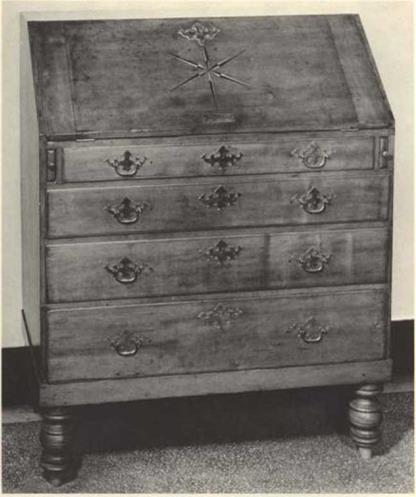

Tables and desks constituted the great majority of their work. Of the documented objects, 62 were desks and 223 were tables. Many were simple utilitarian pieces of turnirnre made of maple or pine (fig, 13). However, these craftsmen also made elaborate card and tea tables as well as veneered desks with inlaid stringing and stars. On June 13, 1738, John Mudge billed his employer.£3:3:0 for a "Larg Scdor desk widi a star and scolup Jr os, no well nime, lap beeded and pi lor dros.”-[20] Such a desk probably resembled one owned by die American Antiquarian Society (fig. 14). "No well nunc" indicates that insufficient space was available for a concealed well, a feature often found in New England desks of the William and Mary style, “Scolup dros" may refer to cither the shell carved drawers of a desk interior (fig. 80) or the small arched drawers above the pigeon-

Tables and desks constituted the great majority of their work. Of the documented objects, 62 were desks and 223 were tables. Many were simple utilitarian pieces of turnirnre made of maple or pine (fig, 13). However, these craftsmen also made elaborate card and tea tables as well as veneered desks with inlaid stringing and stars. On June 13, 1738, John Mudge billed his employer.£3:3:0 for a "Larg Scdor desk widi a star and scolup Jr os, no well nime, lap beeded and pi lor dros.”-[20] Such a desk probably resembled one owned by die American Antiquarian Society (fig. 14). "No well nunc" indicates that insufficient space was available for a concealed well, a feature often found in New England desks of the William and Mary style, “Scolup dros" may refer to cither the shell carved drawers of a desk interior (fig. 80) or the small arched drawers above the pigeon-

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

|

13, Table. Eastern MiuachusetH, e. 1730-1760. Maple and white pine; n. zjVa inches, W. її inches (open), d. jiV, inches, (The Henry Francis J11 Font Winterthur Museum.) |

holes.^ The reference to pillared drawers describes the narrow document drawers with applied pilasters, seen on many Boston cigli – tcenth-ccntury desks (fig, tj),

Holmes’s workmen constructed 16 desks and bookcases and 16 chests of drawers. To decorate these large pieces of furniture, they often applied carved or inlaid shells. In 1733 William Randle was paid for gilding two carved shells, probably for a high chest (fig. id).

13. A desk lithe Museum of Fine Am, ІІІИІИІ, has 5n1.1l] arched drawers above tile pigeonholes and a concealed well in the desk interior. See Richard H. Randall, Jr., AmtrifM ЙЦЯїНип 14 the Mutevm ojPint Arts, BejJjm (Boston, Itjdi), fig. 5j,

|

|

14, Dfsx, Гдіісгп Massachusetts, с – 173.0—17^0. Cherry and white pine; h. 46% inches, w, $6 inches, n, tg1/: inches. (American Antiquarian Society; photo, К і chard Mrtr] LLJ Aiiordmg to family tradition, this desk was owned by Goinnor JatnrS licwJoin [1J16-1790) dfBoStalt. FtelanJ brasses arc replant!.

Tour years later Richard Woodward charged Holmes eighteen shillings for “putting in 1 Shell" and one pound tor ‘ Setting ; Shells."3* These later references document the difficult and expensive task of in-

36. Richard Woodward го Nathaniel Holmes, Boston, VI, Accounts Current, December і 2, *737, Bourn Papers (Baker Library, Harvard University),

|

|

15. Imteiidb o< Dqs r-on-FUjSme Showing Rillahed DtAwm. Boston, c. 1740-1770. Mahogany, maple, tulip wood, and white рте: л. 4a1 „ inches. w. inches, D. inches. (Museum of Fine Arts, Roseau, Gift of Mr. and Mrs, Henry Herbert Edcs. 36.34; photo, Rirhird Cheek.) For an overall view of the desk, see Richard H, Randall, Jr., America Furniture in the Miwvm of Иле Arts, Best?» {Boston, 1765). p, 74- Averting to family tradition, this desk was owned by Jedidiak Parker (iem j rjtfi) of Boston.

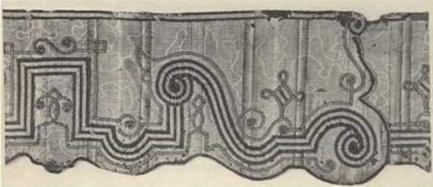

Uyittg strips of wood in a radiating pattern (fig. 17). String inlay was ал even more common decorative motif John Mud go constructed "a Case of dros and Cabell stringed” in October, 1738, and a month later made "a Case of drawers soled ends and stringed.”’7 The earlier reference suggests a matching high chest and dressing table with siring inlay. The latter may refer to a veneered high chest with solid sides decorated with stringing.

Holmes s workmen enumerated only twelve other pieces of furniture in their bills. In 1737 Richard Woodward constructed wall brackets and a bureau table (fig. ій).ЗЙ His Boston colleague, Thomas

37-John Mudge to Nathaniel Holmes, Malden, Massachusetts. January n, 173л. ІЗ.514 (Winierthur Libraries, Jojeph Downs Manuscript Collection),

3*. Thi* is one of the earliest references to an American bureau table. According to Nancy Guyne Evans, the form did nut become popular in New Filmland until after 1750. Evidently Woodward constructed an elegant table, for lie charged Holmes sis pounds, a sum equivalent so chas for a large desk. Richard Woodward to Nathaniel Holmes, Boston, Vt, Accounts Current, December n, 1737, llouni Papers (Maker Library, Harvard University). See also Nancy Coyne Evans, "ТІМ Bureau Table in America," Winterthur Portfolio 1Ц (Winterthur, Delaware, I! K"7), ГР-

|

|

|

|

|olmsont made a tea chest and frame, a tankard board, and a double chest of drawers. None of Holmes’s craftsmen working outside the city produced similar one-of-a-kind items.

|

These workmen charged Holmes for the amount of labor involved in making or assisting on a piece of furniture. A standard cost was often set for each form. Tables, for example, were priced according to their length. Richard Woodward charged eleven shillings per foot for cables in 1736* A year and a half later he demanded an extra shilling per foot, no doubt reflecting in Hat ion in colonial Boston. The price of desks also varied according to siic. John Mudge charged £2:10:0 for his standard desk and £1 :i :0 for a smaller version. Any

ornamentation increased the COST, For a desk with pillared drawers, Mudge added two shillings to his standard sum. Veneering, a popular form of decoration on Boston furniture, increased the cost of construction. In 1734 Mudge built both solid wood and veneered chests of drawers. The price of the former amounted to £3:2:0 while the latter was £410:0. Occasionally die accounts refer to other details such as stringing, inlaid stars and shells, bracket feet, and toes.39 These motifs varied greatly m price and probably were custom ordered,

Often a single object entailed the work of many craftsmen. According to the Holmes papers, a veneered high chest, similar to that made by Ebenezer Hattshome (fig. 19). required the work of hve men. Holmes himself supplied the lumber, brass ware, and nails to a cabinetmaker who constructed the case. A turner furnished the cabinetmaker with drops, flame fin sals, and columns for tire front of die chest. After the ease was completed, a highly skilled craftsman inlaid the star and may have carved the two shells. Finally, a japanner put on the finishing touches by gilding die shells.

In summary’, the papers of Nathaniel Holmes provide much important data on die cabiiictniakmg trade in the U os ton area during the third decade of the eighteenth century. Although no extant furniture can be traced to Holmes or his workmen, the accounts attest to the quantity of their output, Hopefully, examples will be tound, so that we may some day more accurately judge the skills of these men and the characteristics of their work.

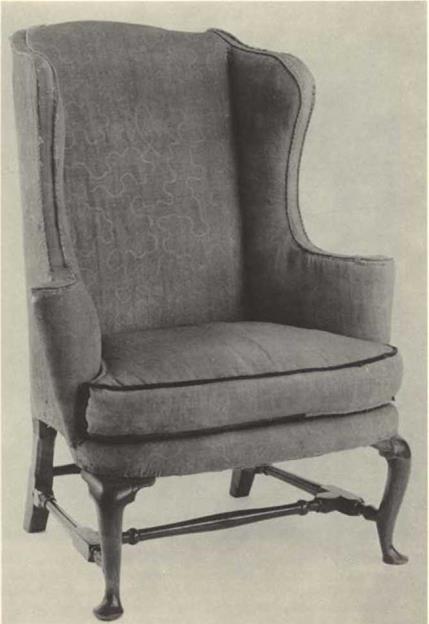

No discussion of the furniture industry could be complete without considering the role of tile upholsterer. During the eighteenth century the upholstery trade was deemed the most lucrative and pres – ti git his craft profession. Its members not only made and sold bedding, bed curtains, and upholstered furniture, but also imported all types of textiles and dry goods for resale. Thomas Fitch and Samuel Grant were two of Boston’s wealthiest upholsterers. A study of their

ЗУ – Tim prnbably refer to the uiitisu. il adspiitiou <>fdie Spanish foot seen 011 the japjnncd high then nude by John Pimm (fig. 37). Similar feet appear qq dressing tables at Historic Deerfield and the Museum of fine Am, Uostuti.

|

|

careers demonstrates the reasons for their success as welt as die activities and products of die upholsterer in colonial Boston.

The soil of a local cordwaincr. Thomas Fitch was bom on February j, 1669.[21] His father died when he was only nine, Apparently his mother apprenticed him to a Boston upholsterer, perhaps Edward Stuppen, an eminent English-bom mcrchant-u phobterer who moved to Philadelphia about 1688. Fitch later corresponded frequently with Shippeu and often sold goods in Boston for his Pennsylvania friend, in 1694 he married Abicl Dan forth, the daughter of the Reverend Samuel Danforth of Roxbury. During the following years he established a highly profitable upholstery business and became a respected man in the community. He held numerous public offices including selectman, moderator, town auditor, and representative to the General Court. His daughters married men of high standing, Martha married James Allen, a prosperous merchant, and Mary wedded Andrew Oliver, later a lieutenant governor of the colony. When Thomas Fitch died in 173(1, hL‘ left a personal estate of ^3j88’8:ll, He also owned several houses in Boston and thousands of acres in many newly established towns in Massachusetts,[22]

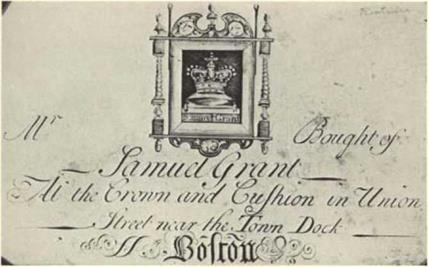

Fitch trained Samuel Grant in the upholstery’ trade.[23] [24] [25] Born in 1705, Samuel was die son of Joseph Grant, a local boat builder.[26] He married Elizabeth Cookson in 1729 and they raised six children over tile next twcmy-fivc years, Like his former master, Grant held several important town positions. Between 1747 and 17J7I1C served as town selectman, in 1768 as town moderator. At his death in 1784.

lie gave the bulk of his estate to Moses Grant, his cm I у surviving son.’14

Fortunately for historians of the decorative arts, several volumes of the account books and letterbooks of Thomas Fitch and Samuel Grant have survived-’15 With these documents it is possible to focus on die lives of two Boston upholsterers during the years 1720 to 1740. Fitch established an extensive trading network throughout the colonies, specials2ing m the distribution of English textiles. In addition, he sometimes imported other goods which might sell well in die colonies. In a letter to a New York merchant he stated that "besides all Sorts of Upholstery goods as rugs blank (e|ts quilts ticks broad si rip &c.” he also offered for sale "a Pci 11 {Parcel] of Ironware and nails."46 Further correspondence shows that Fitch sold spectacles, penknives, candlesticks, stockings, caps, clothing materials, and other dry goods to merchants in every coastal port from Halifax to the West Indies. To transport these goods he owned shares in several ships.

In addition to his mercantile pursuits, Fitch operated an upholstery shop where lie or his workmen produced beds, bolsters, mattresses, curtains, and furniture. Some jobs were done for bis clients in their

|

|

20, Вїр Valance. Satem or Hcutoti. c, 1720-17+0- tnglisJi tbtyney, w. іі’/л inches, (Essex Institute, Salem, Massachusetts.)

homes. In 1724 he charged George Cradock £0:1:6 for “puting up a bedstd & Curts."[27] [28] A year latex Fitch completed the ‘wallpapering of a room for John Jchyl. The cost was £2:12:9 for seventy-eight and a quarter yards of binding, papering tacks, and labor. Jckyl had purchased the paper himself and employed Fitch only to hang itrje ТЪс great majority of Fitch’s patrons were wealthy merchants, lawyers, and physicians of Boston, Newport, and New York, The list included John Read, Esquire. of Boston, Edmund Quincy, Esquire, of Braintree, Isaac Lopez of Newport, and William Beckman of New York. For such a prominent clientele, Fitch made every effort to provide fashionable furnishings. He sometimes wrote to his friends in England for patterns for bed hangings. In 1725 he instructed John East, an upholsterer in London, to “Get your best draughtsman to draw a few of ye newest fashion’d & pretty neat airy Vahts [Valances] hcaddoths headboards & Testers and a comish [cornice] or two: and ye figure of a counter pane if they arc in fashion."44 Several times in the next five years. Fitch requested additional patterns, In an illuminating letter on the taste of Bostonians, lie asked

East "to send me a partem or figure of Fash ton able Valia nee & the figure of a headboard & hciddenh done by some ingenious wort man to be put on a flat headcloth & as the fashion I think is very plain, lie may send some with a little more work, our people too generally choosing them somewhat showy.’>so

Fitch’s letters explain the dose similarity between English and American bed hangings. An example at the Essex Institute (fig – 20) resembles the end of a valance illustrated in a scene from A Harlot’s ProgKiS by William Hogarth (fig. 21], Another valance, originally

jo. Ibid., December 8, 1731.

|

21. А Hahloi’s PnocAtss. plate ti. Drawn and engraved by William Hogarth, London, i7Ji. Copperplate engraving; H – II7 . Lnchci, w. 141 ^ inchci (engraved surface onlyj. (Mmeuiti sfhtic Ant, Doston, Harvey П. Parker Collection, Г11991,) |

owned by the Robbins family of Lexington, Massachusetts (fig. zz), relates to an English example, also engraved by Hogarth in the two prints. Before and After (fig. 23). Such comparisons demonstrate the attempts of American upholsterers to follow English designs. Using imported fabrics and patterns, they were able to copy the most recent fashions in London,

Fiteh occasionally collaborated with English upholsterers on elaborate bed hangings, A letter to Silas Hooper, a London merchant, in December. 1725, records the joint efforts of two men on different continents to complete a set of hangings:

Now J desire Yo to apply to some Upholder that’s a neat Wurkman and get him to Match this Camblct very exactly with enough of it only for one suec of outside Vallanc and to Cover one set of Cornishes, and make up the outside vail and Cover the Cornishes handsomely and fashionably, and cover the head board, wood head Cloth and Testr, with some… Satten and make the Inside Vail thereof. Let the whole be of a good Air or fancy for a room 10 feet high, and trim’d with the same lace of the Inclosed pattern packing up for me full Enough of the Same binding and breed suitable to finish ye Curtains bases and base moldings here.*1 [29]

|

23. Легши:. Drasvn and СП graved by William Hogarth, London, 173-6. Copperplate engraving; и. inches, W. tl finches (engraved surface only). (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation,) |

Fitch intended to use this set of hangings as a model for another "sutc of tile Same which I shall wholly make up here,”52 Such lengthy correspondence suggests the importance of bed hangings in the eighteenth century. For Boston’s gentry they provided a symbol of status

із. Ibid.

as well as comfort. Feather mattresses weighing up to sixty pounds, curtains with over thirty-five yards of expensive worsted material, and elaborately carved high-posted frames made beds the most costly objects in the colonial home.53

Fitch succeeded in business by capably serving an elite clientele. Evidence indicates that his apprentice, Samuel Grant, sought to do the same. In 172Б Grant had completed his indenture and was working at the Crown and Cushion in Union Street (fig. 24). Fitch helped him to begin business by selling him upholstery materials on credit. Of additional importance were the contacts that Grant had made while under his master s guidance, After his apprenticeship he patron ized a London upholsterer used by Fitch, employed the same chair maker to make bedsteads and chair frames, and sold goods to many of the same persons.54 After Iris master’s death in 1736. Grant, in effect, inherited both the business and reputation of Thomas Fitch.

The scale of iiis activity, however, never reached the magnitude of his master’s enterprise. Grant never developed the extensive export trade which characterized Fitch’s career. Perhaps increasing competition from Newport and New York merchants impeded his chances of success in the coastal business. More likely he simply lacked die capital to finance a complex mercantile operation.

Grant rarely imported his textiles directly from English metchants. Whereas Fitch had dealt with as many as five London factors at one time. Grant requested upholstery from only one man and. in this case, the orders were small. Without a far-reaching export trade. Grant had no means of repaying English merchants widi goods marketable in London. Fitch had sent furs from New York, tar from the Carolinas. logwood and sugar from the West Indies, and whalebone to his factors in England. He also collected bills of exchange

jj. Florence M. Monigutnery, Ptmirtf ТвсЩеі: Englith «nJ Апіегкая Світлі and Lilian ijt>e~i$jo [New York. 1970). pj>. 49, JS-jS.

34, Tin: uphukicti-i wi: Juhn East. See Sumicl (jiini, Account Book, April 11, >7SS, p. sSj (Massachusetts Historical Society). Thedumnakcr was Edmund Perkins. See Thomas Filch, Account Book, January 13, 1713, p. 3.1 з (Massachusetts Historical Society); Samuel Grant, Account Book, February si. i7so, p. JS (MispchuKttj Historical Society).

|

24. ТіЛИї Слїі) Or S Амиш. Chant Attributed toThoinuJ&butfnn, Hwtan. 17J-6. Rcstritc of copperplate engraving; H. 4 inches, w. <S% inches (engraved surface only). (American Antiquariin Society.) |

from merchants in other areas which helped to pay for English textiles sent to Boston. Grant, on the other hand, conducted л small export trade along the Atlantic Coast. His only major commodity for shipment to England was beeswax. Consequently, he was forced to rely on merchant-middlemen in Boston for most of his goods. During the year 1732, he purchased upholstery materials, garlits (a coarse linen), and calicoes valued at,£1597 from Charles Apthorp, a leading local importer. He also dealt with James Allen. Pitch’s son – in-law and a wealthy merchant, Jacob and John Wendell, two brothers in business together, and Samuel Cary, a ship captain. In repayment for textiles, these men accepted furniture and die services of an upholsterer. Retween 1728 and 1740 Grant delivered 141 chairs to the Wendells, 214 to Apthorp, and 400 to Peter Fancuil, another prosperous importer. Most of these chairs were packed into boxes, loaded onto ships owned by the merchants, and sold at distant ports. Some were used to furnish ships* cabins, while others were requested by the merchants for their own homes or those of relatives and friends. In

1732James Allen ordered з bed, couch, easy chair, and twelve leather chairs for delivery’ to his brother, Jeremy Allen.55

Grant’s success as an upholsterer depended on his relationship with local merchants. From 1728 to 1740 his services were constantly in demand and, as a result, lie never became a risk to his creditors. He profited by purchasing large quantities of textiles at wholesale prices and reselling them in small lots at higher rates. His charges for labor were minimal wrhcn compared to the costs of materials. On July 12, 1731. he billed Jacob and John Wendell for two easy chairs. The frames breach cost £1:17:6; the curled hair, feathers, linen itching, and webbing for the understnurture cost £2:5:8; the outer material and binding was £31 1:6; and the labor was £і:ій:о,56 The labor charge amounted to only one-sixth of the total. The labor charge for a pillow, mattress, or bolster was even less. Grant billed George Rogers £12 for feather bedding which cost only £0:5:0 to make.57

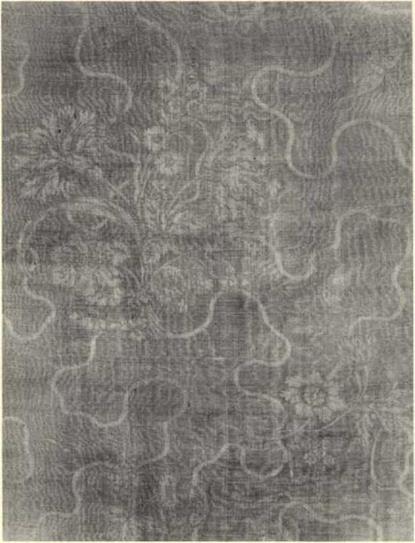

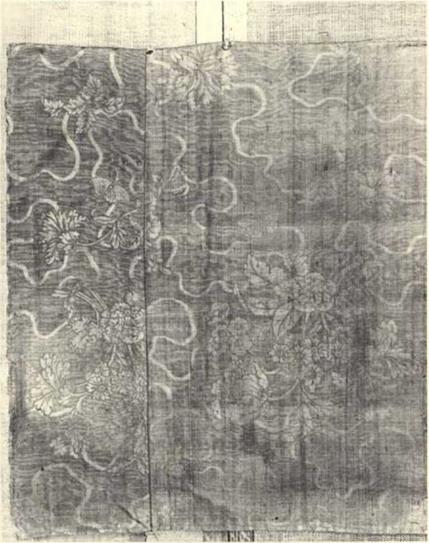

Besides describing the business activities of Thomas Fitch and Samuel Grant, the account books provide insights into the popularity, appearance, and style of textiles and furniture. English worsteds were by far the most common textiles used in home tu mi shin gs. During a four-year span between 1728 and 1732, Grant used chcyncy, a coarse-grained or ribbed worsted, for about ninety percent of his curtains and chair coverings. Ten years later harrareen,56 another worsted closely related to chcyncy, superseded it. From 1738 to 1742 harratoon was employed for sixty percent of his furnishings. Chcyncy dropped to about thirty percent during the same period and after 1742 disappeared almost altogether.

55. Samuel Grant, Account Book, February 4. 17] 1. p. 1 j; (Massachuscrts Historical Society).

Ibid,, July 12, 17JI, p, uKS,

Ї7- Ibid.. July 19, 17J?, p. $90.

sfi. Harritcen had been in limited use in Boston from at least 1726. Thomas Fitch cotiinicnied on the new fabric in that year, when he wrote to a patron in New York: "I concluded it would be difficult tu yet Such a Ciiliminco as you propos’d to Cover the Ease Chair, and bvcinj a very Strong thick Hat ratine which is vastly more fashionable and handsome than а CaUhninco I have tent you an Ease Chair Cover’d w[LJtb sd Hirntteti wjlnith I hope will Sute Yea." Thomai Pitch to Madam Ноіідіагн. Война, March 9, 172C, Fitch Letterbook (MaAchutetta Historical So – d«y).

|

|

Easy Ch Alh. Boston area, c. 1740-1745. Walnut, white pine, and English harratccn Or moTwn (original)і if. jH inches w. 3514 inches, D. 34 inches. (The Brooklyn Museum. Henry L, !1j tier man, Maria L, Emmons, and t:harl« Sttwan Smith Memorial Funds.)

|

|

3)6, DfTAiL of tHE Влек Of an Easy Chair. Boston area. c. 1730-1770. Mahogany, лтіріс, and English harrateen or moreen (original); H. inches. W. 33 inches, о. іб inches. (The Bay00 Bend Collection of the Museum of fine Arts, Houston,) For an overall view of the chair, see American Art: Furniture, Painting, and Sib/tr in tltt Bayou Haul Collertitm (Houston, 1У74). no. 8<f.

|

|

27. Fbagmehtoi а Беп Cuhtain. Salem or Doiton, c. 1750-1770. English hirnuxn tar mor«n. (Essex fnstitutc, Salem, Maiuachnscm.) According to family tradition, this curtain wai ward by tianiii and Sat ah Saunders of Salem who were married in 17741.

|

|

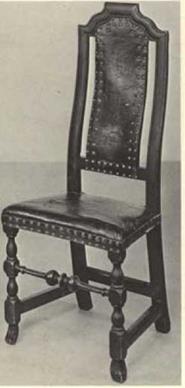

28. Анмсилги, Hfcscnn area, с, 1710-1715. Maple, red oiltT and Russia» leather (original); it, 33% inches,’®. 24inches, d. 27і/, inches. (The Henry Francis du Pone Winterthur Museum.) Chairi mitrtd with Дииідіт Jtalhrr um often said by Thomas Filth Ьфіе tyiy

Today it is difficult to distinguish between these two fabrics. They are part of a group of heavy worsteds which include camlet and moreen. During the eighteenth century both were often decorated with watering, waving, and figuring (figs. 20 and 23). In watering, the cloth received a special preparation with water and then was passed under a hot press to give a smooth and glossy surface. Waving was done by rolling the cloth under an embossed cylinder to create a rippling design, figuring was simply the scamping of flowers and figures onto the fabric by mcani of hot icons.5*5 These impressed patterns can easily be seen on the back of an easy chair at Bayou Bend (fig, 2й) and on a fragment of a bed curtain at the Essex Institute (fig. 27). Both examples are red or crimson, die most common color named by Grant; blue, green, and yd low followed m popularity.

Boston upholsterers often covered die it chairs in Leather. Fitch and Grant used Russian and Mew England leather, The first, imported into this country tlirough England, was common during the early years of the eighteenth century, but by 1723 had become difficult to obtain. On June 26, 1727, і itch wrote to a Colonel Coddington in Massachusetts that he had “no Rush і a leather Chairs nor other, nor Leather to make them of. Kusshia Leather is so very high at home that It wont answer. If I had any they would Certainly be att Your Service, I think Mr Downs lias New England red Leather, but tire re’s no Rushia in Town,’™

After 1730 Boston craftsmen turned primarily to New England leather. This material was usually made of seal or goat skins. Grant imported hundreds of seal skins which he sold tojoseph Caleb a local tanner, The skins were dyed black or red, cut into the shape of chair seats, and returned to Grant,

The account books of Thomas Fitch and Samuel Grant are most helpful in describing the styles of chairs made iti Boston between 1720 and 1740. On May 4, 1720, Fitch charged Isaac Lope? £ 16:210

59. Abbott Lowell Cummings, Bed Hangings: A Trealist &n Fabrics tmd Styles iti ike Curtaining of Beds itips-lSjO (Portland, Maine» i960» P-

60, Thomas Fitch Ш Colonel Coddington, Boston, June iri, 1727» Fitch Letter book (Massachusetts Historical S(jdety).

29,

|

|

Рлги of Side Сил ген. Boston area, c. 1710-1730. Maple, oak, and leather (original); 11. 44% inches, W. 1 в % inches, D. 13 inches. (Private collection, Milwaukee, Wisconsin: photo, Gitisburfc and Levy, 1ne„ New York City,} G’fairj of fh’j type were Sold by ThoitiOi Fitch after 1714.

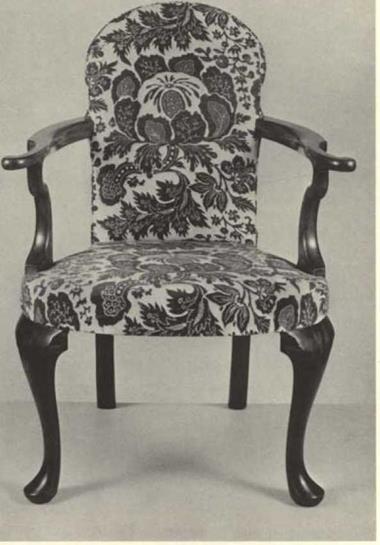

for"u carvd Russhia Leather chairs St i elbow [chair]. lt The reference to carving suggests that these were in the William and Mary style. The large elbow chair may have been similar to an armchair in die Winterthur Museum which still retains its Russian leather upholstery (fig. 28), In 1724 Fitch began to sell crooked-back leather chairs without carving. These chairs, probably resembling a pair in a private collection (fig. 29). were often called boston chairs and remained popular items for export during the following two decades.

fii. Thutnas Fitch, Account Book, May 4. 1710, p. B4 (Massachusetts Historical

Society).

|

|

30. Armchair. Nevr York, c. 1730-1750. Walnut and linen (not original);H. 36 inches. W. ібу* inches, n. 13 inches. (The Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum.) This (hair Jeseended in the Tihbits family of New York, Chairs with similar round seats were sold by Samuel Ctant in tjxy.

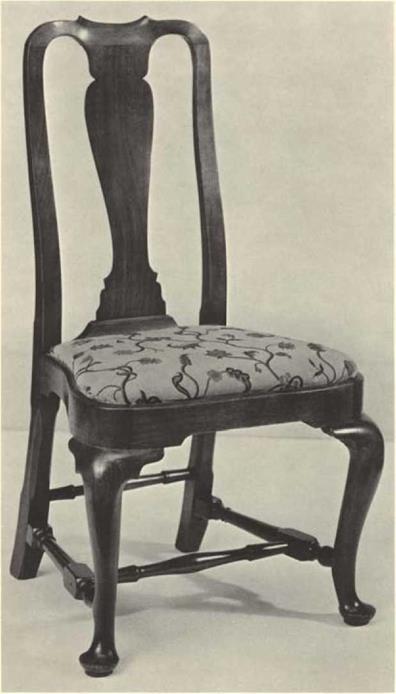

Furniture in the Queen Anne style was introduced during the late 1720s, On October 14, 1729, Gram sold an upholstered chair of red chcytiey, described as "New fashion round scat."*’2 Such a chair was probably related in form to an example attributed to New York (fig. 30). The round scat reflected an increasing emphasis on the curved line, a chief characteristic of the new style. In 1730 Grant recorded the sale of a couch frame with ‘‘horseboiiL1 feet,"*3 Apparently the term referred to a cabriole leg. perhaps with a notch near the bottom of the back of the leg resembling the indentation just above a horse’s hoof.*^ On January 22, 1732, Grant charged die mercantile firm of Clark and Kilby ,£12 for “6 Lead) Chairs maple frames hosbone round feet & Cusn Scats/1’5 These chairs presumably had cabriole legs, pad feet, and slip scats. It seems likely diat they also had straight stiles, curved crest rails, and vase-shaped splats or banisters, as they were often called. Grant, in April, 1732, billed John lireck, a cooper in the Nordi Fnd, for "8 Lcalhr Chairs horsebone feet & bamstfer] backs,”6* Such chairs, no doubt, resembled one illustrated in a portrait ofAfrs. Andrew Oliver іmi Son {fig. 31} by John Snubcrt. This important painting of the daughter of Thomas Fitch wras completed only ttvo months after Grant first mentioned the term ‘’banister,"

Many examples of these Queen Anne chairs have survived. One with a history of ownership in the boston area {fig, 32)1$ related in the shaping of the crest rail to Mrs. Oliver’s chair. In later versions of the form, the crest dips in the center m form a yoke (fig. 33).

Between 1732 and 1740 Grant continued to produce leather-backed William and Магу chairs, upholstered armchairs with cheyncy and harrateen coverings, and Queen Anne chairs with solid splits. Octa-

fii. Samuel Grain, Account Book, October 14, 1729, p. 29 (Makati msec is His – гогіеді Soticry).

6j. Ibid., November 11, 1730, p. Gs-

This пенсії is often seen cm Boston furniture of the Queen Aimc srylr. See, fur

Cliaitl pic. a japanned high cllcst in the сиіікііїт of tile New I [a veil Colony Hiitorical Sudd у. Elizabeth Rhoades and Brock Jobe, ” Recent Discover ієн in Boston Japanned Furniture,” ilprfiijiifj, cv (May, 1974). loBa-topt.

Samuel Grain, Account Book, January 21. 1732, p. 131 {Massachusetts Historical Society).

йб, ibid,, April 29, 1732, p, 14(5.

|

|

31. Mas, Л нпяе w Oli V£it л N D Son. Painted by John Smiberr, Боя on, 1732, Oil on canvas; и. jo’/j inches, w. 40% inches («dading frame), [Collection of Andrew Oliver, Jr,, Daniel Oliver, and Ruth F. O. Evans: photo, Frick Art Reference Library,)

32. Side Chair. Boston, am, c. 1730-1750. Walnut and nuplt; H. 44% inches, w. i£l/4 inches, D, ji% inches. (The Bay cut Bend Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.) This chair is iJcns’rdf to one in a private collection tuiib a history of PV’nmhip ftI file Batlort /trea.

|

|

33. Side Chair, Boston, c. 1735-1760. Walnut; h. 40% inches, w. 20% inches, 0,16% indict, (Museum of Fine Arts. Boston, Clift of Mr, and Mrs, Henry Herbert Edrt, 36.21.} According to family tradition, this ihait was owned by John Leach (1714- r^j of Boston.

|

|

14, Side Си л is. Boston area, c, 1735-iyfo. Walnut and maple; H. inches, w. л1/а inches, d. i«y4 inches, (YaJe Uni verity Art Gallery, MibcL Brady G;tf van Collect ion.) AiiOttUng tt) family tradition, this chair rt (netted by /‘Jn’jriJ Hoi у eft. President of Hantard Collegefiom 1737 to 176$.

sionallv embellishments were added to these forms, [n 1733 Gram sold some chairs with claw feet, A year later he first produced ones with compass-shaped seats (fig. 34). Throughout the later period, however, he presented no radical changes in style, evidence of the continued popularity of earlier forms in Boston.

This survey has focussed on Boston furniture craftsmen of the early eighteenth century and the objects they produced. In an industry with hundreds of workmen, many practiced specialized professions. Japanners, for example, were able to concentrate on the decoration offuniimre and looking glasses, a very sophisticated specialty which required a large and wealthy clientele. No other city offered Similar opportunities for specialization. Furthermore, as the Holmes accounts reveal, close contacts existed between rural and urban artisans in the Massachusetts Bay area, raising the question of how to discriminate between country and city cabinetwork. When men received materials from Boston, they may also have been given designs or patterns from their employer. Holmes provided sets of veneers to his workmen in Malden. These items, already cur into certain shapes, could easily have been used to build a standard chest or desk which differed little from Boston furniture. Perhaps with the discovery of more documented furniture from Boston and its environs, we may know how these rural examples compared with their urban counterparts.

The papers of Thomas Fitch and Samuel Grant attest 10 the importance of the upholsterer in colonial Boston, Both men supplied not only expensive and fashionable furnishings to wealthy patrons throughout Massachusetts but also cloth, metalwares, and a wide variety of Other dry goods to shopkeepers and country traders. Their careers demonstrate die close connection between the merchant and upholstery trades. The study of eighteenth-century upholsterers, however, is just beginning. Much more data is needed on the less affluent workmen in Boston, Salem. Portsmouth, Newport, and other New England towns, before we can understand how Thomas Fitch and Samuel Grant compared in dieir craft activities and level of success with others in the upholstery trade.

Most importantly, this study has documented the genesis of the Queen A tine style in Boston. Grant first recorded the production of з chair with a round seat in 1729 and one with horsebone feet in 1732. In the same year, William Handle billed Nathaniel Holmes for japanning a ped interned high chest, the earliest reference to the new style in case furniture. The initial creations of horsebone feet and pedi – mented high chests were to flower in the following years into the sophisticated Quern Anne furniture for which boston craftsmanship is famous.