|

When the old King died, at the ripe age of 77, the crown devolved on his great – grandson, then a child five years old, and therefore a Regency became necessary; and this period of some eight years, until the death of Philip, Duke of Orleans, in 1723, when the King was declared to have attained his majority at the age of 13, is known as L’Epooh de la Regenee, and is a landmark in the history of furniture.

There was a great change about this period of French history in the social condition of the upper classes in France. The pomp and extravagance of the late monarch had emptied the coffers of the noblesse, and in order to recruit their finances, marriages became common which a decade or two before that time would hardly have been thought possible. Nobles of ancient lineage married the daughters of bankers and speculators, in order to supply themselves with the means of following the extravagant fashions of the day, and we find the wives of ministers of departments of State using their influence and power for the purpose of making money by gambling in stocks, and accepting bribes for concessions and contracts.

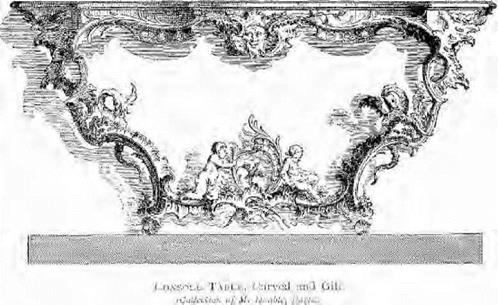

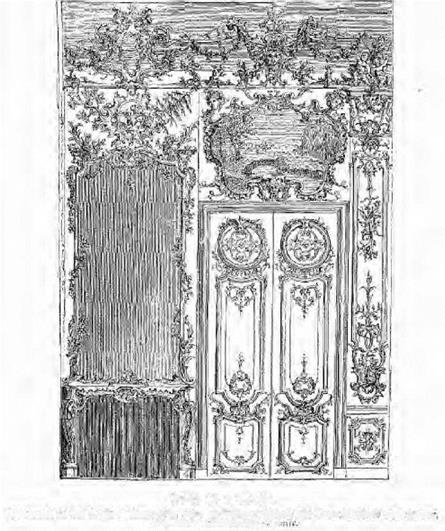

It was a time of corruption, extravagance, licentiousness, and intrigue, and although one might ask what bearing this has upon the history of furniture, a little reflection shows that the abandonment of the great State receptions of the late King, and the pompous and gorgeous entertainments of his time, gave way to a state of society in which the boudoir became of far more importance than the salon, in the artistic furnishing of a fashionable house. Instead of the majestic grandeur of immense reception rooms and stately galleries, we have the elegance and prettiness of the boudoir; and as the reign of the young King advances, we find the structural enrichment of rooms more free, and busy with redundant ornament; the curved endive decoration, so common in carved woodwork and in composition of this period, is seen everywhere; in the architraves, in the panel mouldings, in the frame of an overdoor, in the design of a mirror frame; doves, wreaths, Arcadian fountains, flowing scrolls, Cupids, and heads and busts of women terminating in foliage, are carved or moulded in relief, on the walls, the doors, and the alcoved recesses of the reception rooms, either gilded or painted white; and pictures by Watteau, Lancret, or Boucher, and their schools, are appropriate accompaniments.16

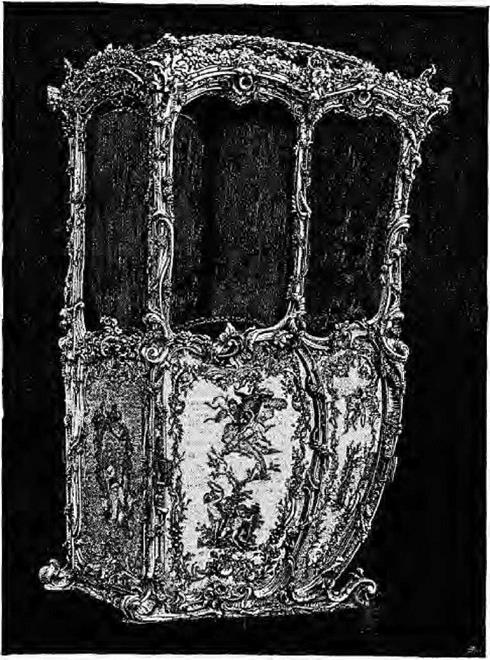

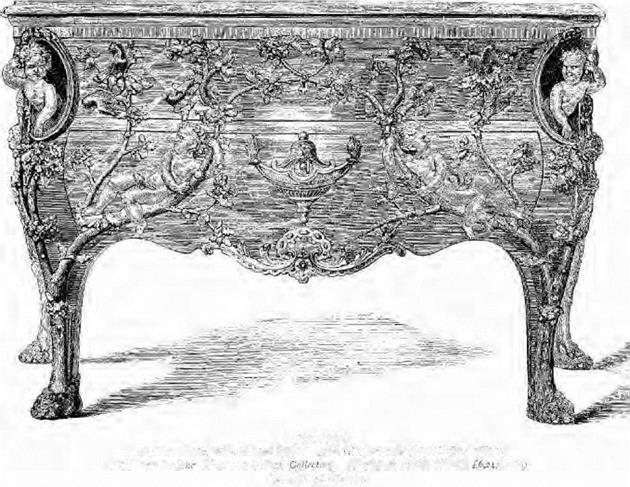

The furniture was made to agree with this decorative treatment: couches and easy chairs were designed in more sweeping curves and on a smaller scale, the woodwork wholly or partially gilt and upholstered, not only with the tapestry of Gobelins or Beauvais, but with soft colored silk brocades and brocatelles; light occasional chairs were enriched with mother-of-pearl or marqueterie; screens were painted with love scenes and representations of ladies and gentlemen who look as if they passed their entire existence in the elaboration of their toilettes or the exchange of compliments; the stately cabinet is modified into the bombe fronted commode, the ends of which curve outwards with a graceful sweep; and the bureau is made in a much smaller size, more highly decorated with marqueterie, and more fancifully mounted to suit the smaller and more effeminate apartment. The smaller and more elegant cabinets, called Bonheur du jour (a little cabinet mounted on a table); the small round occasional table, called a gueridon; the eneoignure, or corner cabinet; the etagere, or ornamental hanging cabinet, with shelves; the three-fold screen, with each leaf a different height, and with shaped top, all date from this time. The chaise a porteur, or Sedan chair, on which so much work and taste were

|

|

|

Part of a Salon.

Part of a Salon.

Diikiuiated in ihc Lon is QniniB bivle sbtvviu^ line carved and £di Спгь-ііг. T’abli and Mirrt-v wich oiijiir cjirkibj}ifcJiL>, – ** ^

|

|

The Louis Quinze cabinets were inlaid, not only with natural woods, but with veneers stained in different tints; and landscapes, interiors, baskets of flowers, birds, trophies, emblems of all kinds, and quaint fanciful conceits are pressed into the service of marqueterie decoration. The most famous artists in this decorative woodwork were Riesener, David Roentgen (generally spoken of as David), Pasquier. Carlin, Leleu, and others, whose names will be found in a list in the appendix.

|

|

During the preceding reign the Chinese lacquer ware then in use was imported from the East, the fashion for collecting which had grown ever since the Dutch had established a trade with China: and subsequently as the demand arose for smaller pieces of meubles de luxe, collectors had these articles taken to pieces, and the slabs of lacquer mounted in panels to decorate the table, or cabinet, and to display the lacquer. Ebenistes, too, prepared such parts of woodwork as were desired to be ornamented in this manner, and sent them to China to be coated with lacquer, a process which was then only known to the Chinese; but this delay and expense quickened the inventive genius of the European, and it was found that a preparation of gum and other ingredients applied again and again, and each time carefully rubbed down, produced a surface which was almost as lustrous and suitable for decoration as the original article. A Dutchman named Huygens was the first successful inventor of this preparation; and, owing to the adroitness of his work, and of those who followed him and improved his process, one can only detect European lacquer from Chinese by trifling details in the costumes and foliage of decoration, not strictly Oriental in character.

|

|

About 1740-4 the Martin family had three manufactories of this peculiar and fashionable ware, which became known as Vernis-Martin, or Martins’ Varnish; and it is singular that one of these was in the district of Paris then and now known as Faubourg Saint Martin. By a special decree a monopoly was granted in 1744 to Sieur Simon Etienne Martin the younger, "To manufacture all sorts of work in relief and in the style of Japan and China." This was to last for twenty years; and we shall see that in the latter part of the reign of Louis XV., and in that of his successor, the decoration was not confined to the imitation of Chinese and Japanese subjects, but the surface was painted in the style of the decorative artist

of the day, both in monochrome and in natural colours; such subjects as "Cupid Awakening Venus," "The Triumph of Galatea," "Nymphs and Goddesses," "Garden Scenes," and "Fetes Champetres," being represented in accordance with the taste of the period. It may be remarked in passing, that lacquer work was also made previous to this time in England. Several cabinets of "Old" English lac are included in the Strawberry Hill sale catalogue; and they were richly mounted with ormolu, in the French style; this sale took place in 1842. George Robins, so well known for his flowery descriptions, was the auctioneer; the introduction to the catalogue was written by Harrison Ainsworth.

Соымоое

Соымоое

in Faiqueiciv v idi ruisHvc Mourning r. F "tit ТЗіґл. іс yrobubiy ‘-•> Corner і iFprinai. if ■ ЇГллч’,’ті’ч Гоїш. – і. Р»«сі:ал.? .1Н7*»<,.->ч’лп|и <tr-

Lfihfff К’.’. Рїцтоі.

The gilt bronze mountings of the furniture became less massive and much more elaborate: the curled endive ornament was very much in vogue; the acanthus foliage followed the curves of the commode; busts and heads of women, cupids, satyrs terminating in foliage, suited the design and decoration of the more fanciful shapes; and Caffieri, who is the great master of this beautiful and highly ornate enrichment, introduced Chinese figures and dragons into his designs. The amount of spirit imparted into the chasing of this ormolu is simply marvellous—it has never been equalled and could not be excelled. Time has now mellowed the colour

of the woodwork it adorns; and the tint of the gold with which it is overlaid, improved by the lights and shadows caused by the high relief of the work and the consequent darkening of the parts more depressed while the more prominent ornaments have been rubbed bright from time to time, produces an effect which is exceedingly elegant and rich. One cannot wonder that connoisseurs are prepared to pay such large sums for genuine specimens, or that clever imitations are exceedingly costly to produce.

Illustrations are given from some of the more notable examples of decorative furniture of this period, which were sold in 1882 at the celebrated Hamilton Palace sale, together with the sums they realised: also of specimens in the South Kensington Museum in the Jones Collection.

We must also remember, in considering the meubles de luxe of this time, that in 1753 Louis XV. had made the Sevres Porcelain Manufactory a State enterprise; and later, as that celebrated undertaking progressed, tables and cabinets were ornamented with plaques of the beautiful and choice pate tendre, the delicacy of which was admirably adapted to enrich the light and frivolous furnishing of the dainty boudoir of a Madame du Barri or a Madame Pompadour.

Another famous artist in the delicate bronze mountings of the day was Pierre Gouthiere. He commenced work some years later than Caffieri, being born in 1740; and, like his senior fellow craftsman, did not confine his attention to furniture, but exercised his fertility of design, and his passion for detail, in mounting bowls and vases of jasper, of Sevres and of Oriental porcelain. The character of his work is less forcible than that of Caffieri, and comes nearer to what we shall presently recognise as the Louis Seize, or Marie Antoinette style, to which period his work more properly belongs: in careful finish of minute details, it more resembles the fine goldsmith’s work of the Renaissance.

Gouthiere was employed extensively by Madame du Barri; and at her execution, in 1793, he lost the enormous balance of 756,000 francs which was due to him, but which debt the State repudiated, and the unfortunate man died in extreme poverty, the inmate of an almshouse.

The designs of the celebrated tapestry of Gobelins and of Beauvais, used for the covering of the finest furniture of this time, also underwent a change; and, instead of the representation of the chase, with a bold and vigorous rendering, we find shepherds and shepherdesses, nymphs and satyrs, the illustrations of La Fontaine’s fables, or renderings of Boucher’s pictures.

|

BUREAU DU ROI. Mr* f. її I rvm V liy KiesmiKv (Cidlcotioii of ” MoWUer NaUcual ") (/’‘іти a pan (not ink Лкппіпк ‘у H Elhw: ,) РКМ1Р<< : l. ol is XV. |

Without doubt, the most important example of meubles de luxe of this reign is the famous "Bureau du Roi," made for Louis XV. in 1769, and which appears fully described in the inventory of the "Garde Meuble" in the year 1775, under No. 2541. This description is very minute, and is fully quoted by M. Williamson in his valuable work, "Les Meubles d’Art du Mobilier National," and occupies no less than thirty-seven lines of printed matter. Its size is five-and-a-half feet long and three feet deep; the lines are the perfection of grace and symmetry; the marqueterie is in Riesner’s best manner; the mountings are magnificent—reclining figures, foliage, laurel wreaths, and swags, chased with rare skill; the back of this famous bureau is as fully decorated as the front: it is signed "Riesener, f. e., 1769, a l’arsenal de Paris." Riesener is said to have received the order for this bureau from the King in 1767, upon the occasion of the marriage of this favourite Court ebeniste with the widow of his former master Oeben. Its production therefore would seem to have taken about two years.

This celebrated chef d’oeuvre was in the Tuileries in 1807, and was included in the inventory found in the cabinet of Napoleon I. It was moved by Napoleon III. to the Palace of St. Cloud, and only saved from capture by the Germans by its removal to its present home in the Louvre, in August, 1870. It is said that it would probably realise, if offered for sale, between fifteen and twenty thousand pounds. A full-page illustration of this famous piece of furniture is given.

A similar bureau is in the Hertford (Wallace) collection, which was made to the order of Stanilaus, King of Poland; a copy executed by Zwiener, a very clever ebeniste of the present day in Paris, at a cost of some three thousand pounds, is in the same collection.