Any consideration of the Korean home and lifestyle must first take into account the fact that Koreans do not habitually use chairs, but sit on the floor, a custom central to the ondol method of heating.

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the plan of the dwelling is the versatility and multipurpose nature of nearly all the rooms. Rooms tend not to have a single, set function. This feature pervades all Korean domestic architecture.

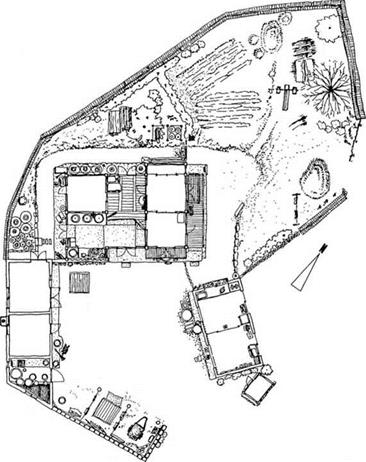

Even in the estates of the elite yangban, all gardens other than the rear garden were an integral part of the family’s daily living space and an essential part of the residential composition. Accordingly, they should be considered as much a part of the dwelling as are the interior spaces.

For purposes of this discussion, different parts of the

residence will be analyzed not in terms of their functions, but in terms of interior and exterior space, or ch’ae and madang. Interior and exterior space can be identified as follows:

Interior space (ch’ae)=enclosed interior spaces (pang) + open interior spaces (taech’dngmd таги).

Exterior space (madang)=open interior spaces (tae – ch’dngand таги) + exterior spaces (gardens).

Interior Space (Ch’ae): Repetitive Juxtaposition of Enclosed and Open Spaces

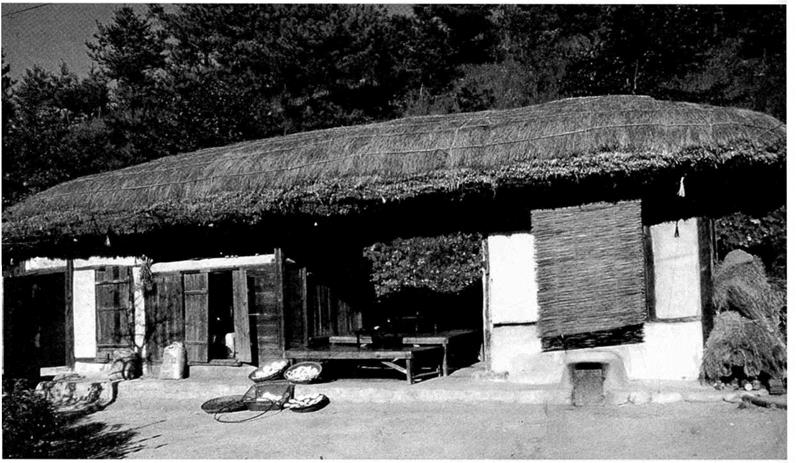

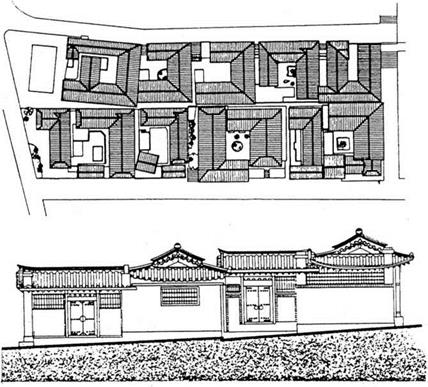

The traditional Korean home comprises three ch’ae, or wings—the anch’ae, sarangch’ae, and haengnagch’ae. The distinction between these three wings of the home was founded on the Confucian sense of order; however, com – positionally, each wing repeats the same pattern of pang (enclosed spaces) alongside taech’ong or таги (open spaces). The juxtaposition of enclosed and open spaces is simultaneously a juxtaposition of elements that are intricate and rough, white and brown, and warm and cold (Figure 104).

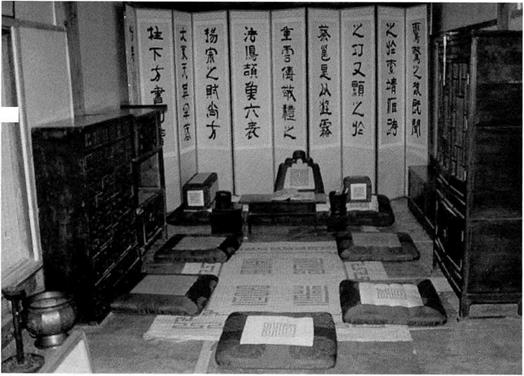

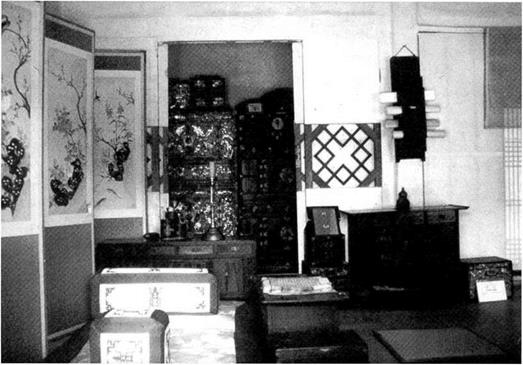

Pang are multipurpose, enclosed rooms of predominantly white hue. In the anch’ae, which was traditionally the wife’s domain, the anbang (inner pang) was furnished and decorated for the use of the female members of the family. Conversely, the sarangch’ae was a social area for the master of the house, so the sarangbang was furnished and decorated for use by men (Figures 105.1-105.2).

|

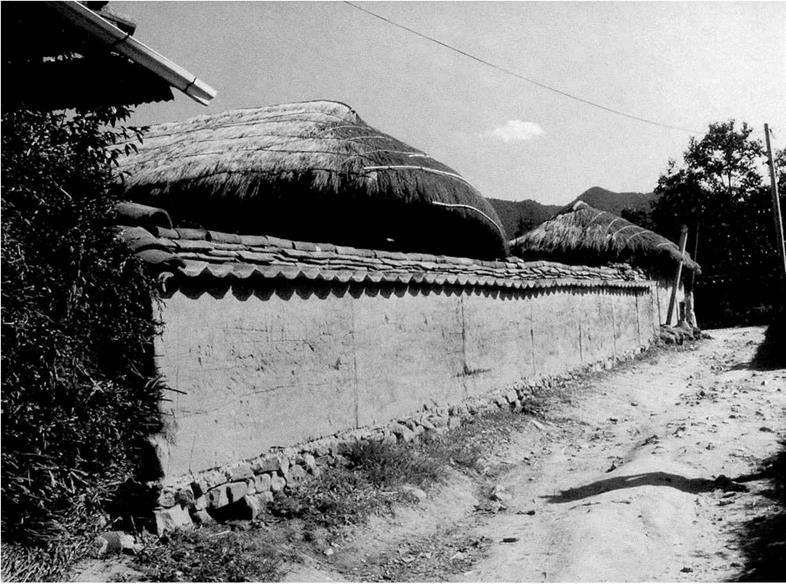

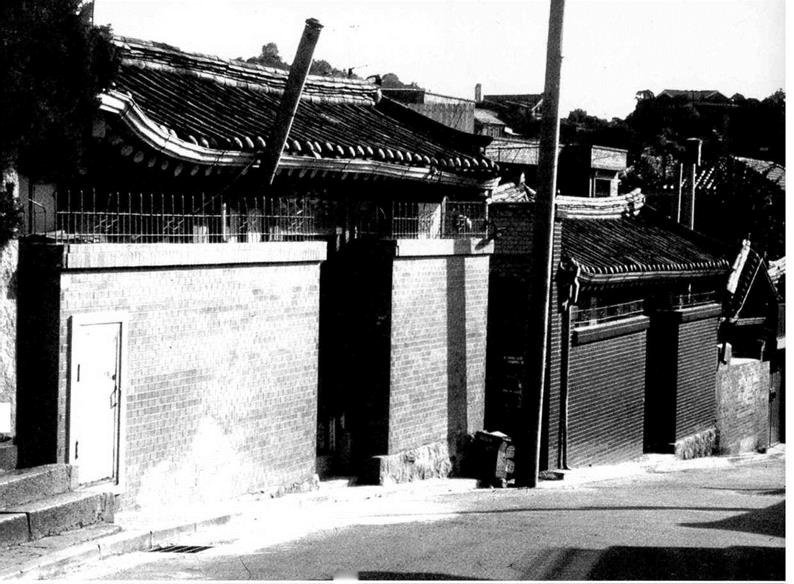

103.1 Exterior view and site plan of a rural village compound (Hahoe). |

|

|

Pang do not have any built-in shelves or cupboards; the only furniture in the room consists of moveable chests and shelves for ornaments. As people sit on the floor, lines of sight are low, so any larger pieces of furniture are kept in either the kolbang or the utpang. All furniture in the anbang, therefore, tends to be ornamental, low, and relatively small, and—since the walls and ceiling of the room are plain white—brightly decorated, frequently with inlaid mother-of-pearl, and colored lacquer.

To derive the maximum benefit from the floor heating, bedding is rather thin; thus it can be folded and stored on top of a chest of drawers when not in use. This means that it is always likely to be in view, and so tends also to be brightly and decoratively colored.

Meals are usually eaten in the ondol-heated rooms, carried from the kitchen on individual low tables (papsang). In summer, however, meals are often eaten in the nearby taech’dng.

Pang are highly versatile rooms with a wide range of uses. They are extremely concentrated spaces, in terms of both size and decor. By contrast, the adjacent taech’dng and mam are very simple—almost rustic—and have somewhat loose spatial definition.

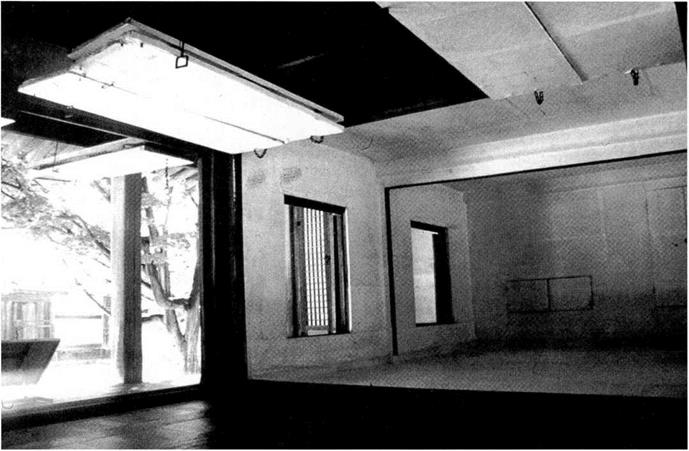

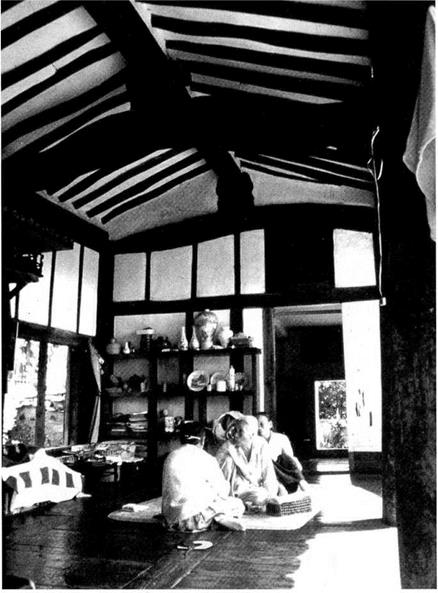

The taech’dng has bare wooden floors, mud or wooden walls, and an exposed beam ceiling. Its northern wall is enclosed by large wooden doors, but its southern side is completely open to the elements (Figure 106). Although its original function was as a ceremonial space, the need for the chilly taech’dng is difficult to understand, even if it does occasionally provide a cooler alternative to the adjoining ondol-heated rooms. Nevertheless, the pang and taech’dng do exist side by side, in stark contrast to one another, and this pattern is repeated throughout the dwelling.

Exterior Space (Madang): Repetitive Juxtaposition of Exterior and Open Interior Spaces

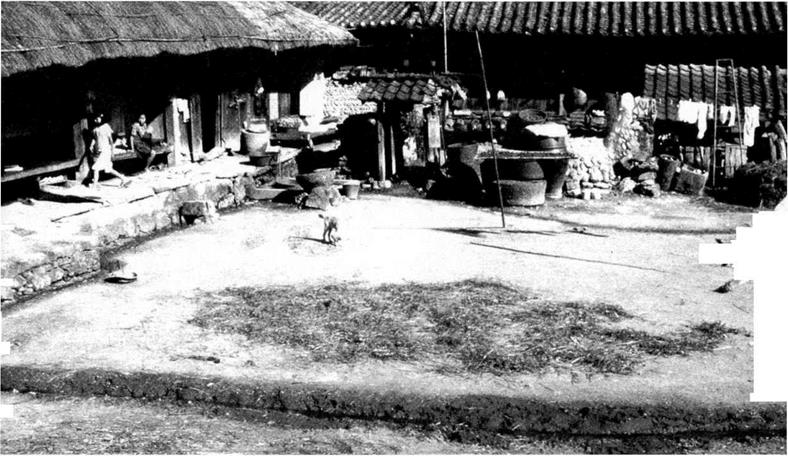

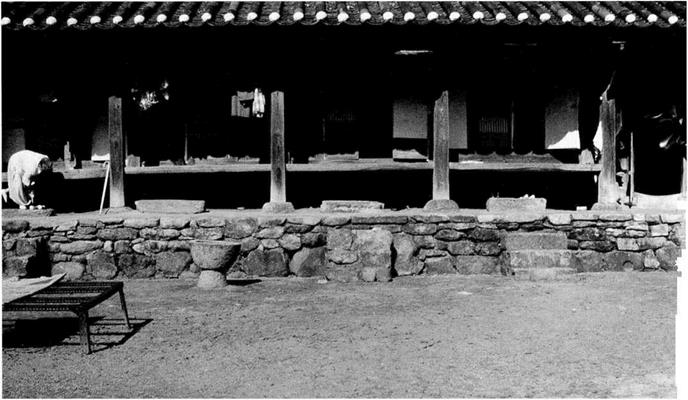

Each ch’ae has its own madang, or garden: anmadang, sarang madang, and haengnang madang. As with the ch’ae, the reason for this distinction can be found in the Confucian sense of order. If we look past their particular classifications, however, we can see that all three of these gardens are fundamentally similar in that they are “white” gardens (areas of bare ground with little or no vegetation). The role of these singularly unornamental “gardens” becomes clear if we consider them in terms of their essential unity with the open interior spaces (i. e. the taech’dng) of the ch’ae interior space to which they correspond.

The floor of the taech’dng is usually constructed of thick boards laid on supports 60-70 centimeters (23.5-27.5 inches) in height. These are set on a solid earthen base built up 50-60 centimeters (about 19.5-23.5 inches) above the level of its adjoining madang garden. The space beneath the floorboards is left open for ventilation. This means that the madang garden is about 120 centimeters (47 inches) lower than the level of the taech’dng floor (Figure 107). In homes that have а питати, or special reception room, the floor level of this room is raised an additional 40 centimeters (15.75 inches) above that of the taech’dng.

The height of the fences or hedges is kept to 130-140 centimeters (51-55 inches), so as not to restrict the view from these rooms. On its northern side, the taech’dng has doors that open out onto the greenery of the rear garden, but its southern side is permanently open to the elements, linking the room to the madang garden. The open and extremely simple taech’dng maintains a link to the enclosed ondol-heated pang that usually adjoin its eastern and/ or western sides, while it simultaneously correlates to the gardens it faces to the north and south (Figures 108.1-108.4).

In yangban estates built near the top of a hill’s south face, the taech’dng is raised high enough to command a panoramic view—beyond the madang garden and the outer wall—which encompasses the lower hillside, forest, plains, and usually a river. The wide doors on the

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

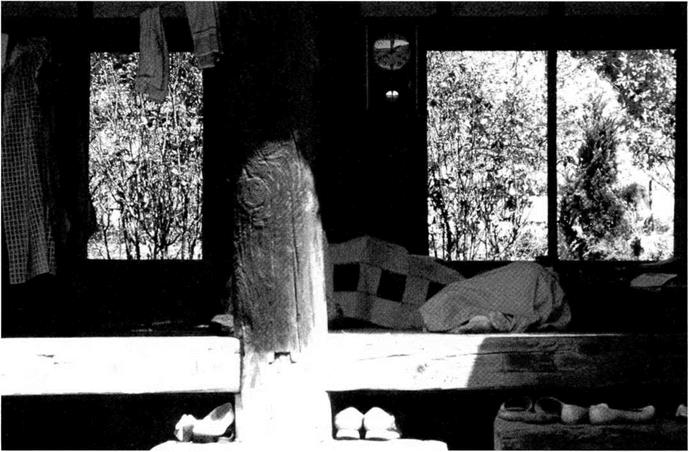

108.1 A view showing the threshold between closed (pang) and open (taech’dng) spaces. |

|

108.2 A view showing the relationship between enclosed space, open space, and exterior space. |

|

108.3 A view showing the relationship between the interior of a taech ong and the rear garden. |

|

108.4 A view showing anmadang lifestyle. |

|

|

|

taech’dng’s northern side frame a view of the green upper slope of the rear garden. The питати (reception room), raised higher still, has the optimal view.