|

1ІГК1-ШШ. rCJRXT^rarli ‘ГНЕ Ті-ТЕ Off ГИЕ XVJ. PfEiOD |

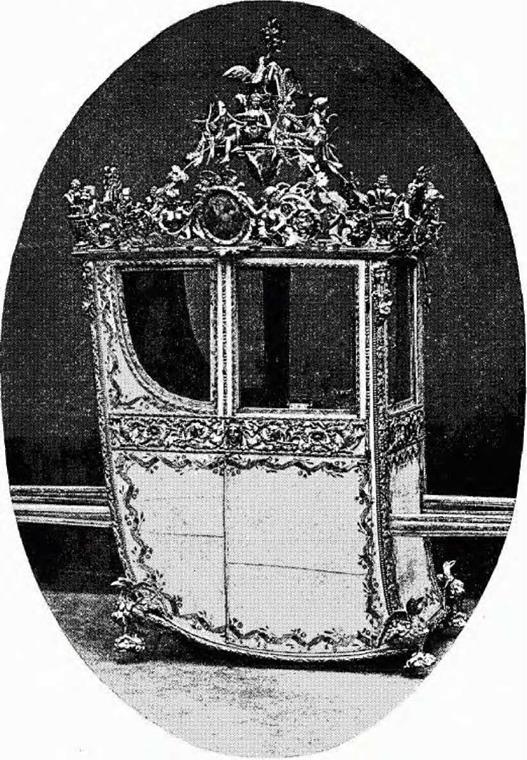

It is probable that for some little time previous to the death of Louis XV., the influence of the beautiful daughter of Maria Theresa on the fashions of the day was manifested in furniture and its accessories. We know that Marie Antoinette disliked the pomp and ceremony of Court functions, and preferred a simpler way of living at the favourite farm house which was given to her husband as a residence on his marriage, four years before his accession to the throne; and here she delighted to mix with the bourgeoise on the terrace at Versailles, or, donning a simple dress of white muslin, would busy herself in the garden or dairy. There was, doubtless, something of the affectation of a woman spoiled by admiration, in thus playing the rustic; still, one can understand that the best French society, weary of the domination of the late King’s mistresses, with their intrigues, their extravagances, and their creatures, looked forward, at the death of Louis, with hope and anticipation to the accession of his grandson and the beautiful young queen.

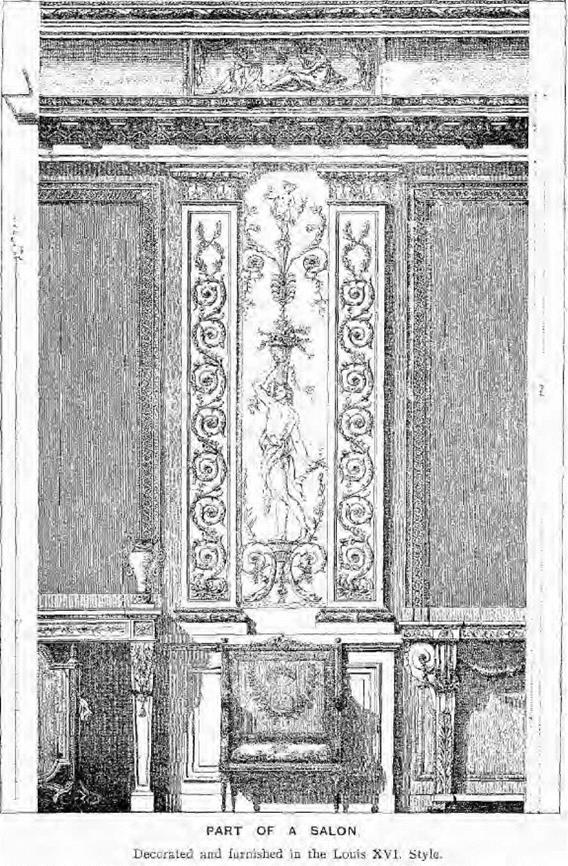

Gradually, under the new regime, architecture became more simple; broken scrolls are replaced by straight lines, curves and arches only occur when justifiable, and columns and pilasters reappear in the ornamental facades of public buildings. Interior decoration necessarily followed suit; instead of the curled endive scrolls enclosing the irregular panel, and the superabundant foliage in ornament, we have rectangular panels formed by simpler mouldings, with broken corners, having a patera or rosette in each, and between the upright panels there is a pilaster of refined Renaissance design. In the oval medallions supported by cupids, is found a domestic scene by a Fragonard or a Chardin; and the portraits of innocent children by Greuze replace the courting shepherds and mythological goddesses of Boucher and Lancret. Sculpture, too, becomes more refined and decorous in its representations.

As with architecture, decoration, painting, and sculpture, so also with furniture. The designs became more simple, but were relieved from severity by the amount of ornament, which, except in some cases where it is over-elaborate, was properly subordinate to the design and did not control it.

Mr. Hungerford Pollen attributes this revival of classic taste to the discoveries of ancient treasures in Herculaneum and Pompeii, but as these occurred in the former city so long before the time we are discussing as the year 1711, and in the latter in 1750, these can scarcely be the immediate cause; the reason most probably is that a reversion to simpler and purer lines came as a relief and reaction from the overornamentation of the previous period. There are not wanting, however, in some of the decorated ornaments of the time, distinct signs of the influence of these discoveries. Drawings and reproductions from frescoes, found in these old Italian cities, were in the possession of the draughtsmen and designers of the time; and an instance in point of their adaptation is to be seen in the small boudoir of the Marquise de Serilly, one of the maids of honour to Marie Antoinette. The decorative woodwork of this boudoir is fitted up in the Kensington Museum.

|

|

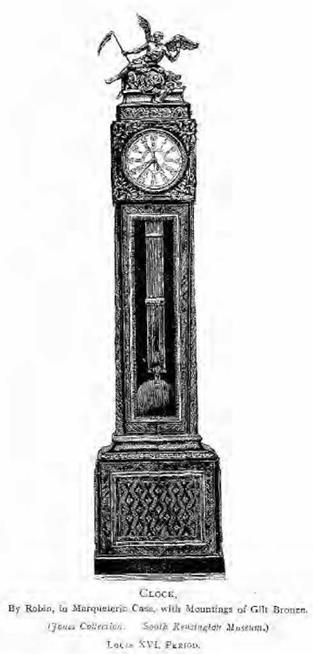

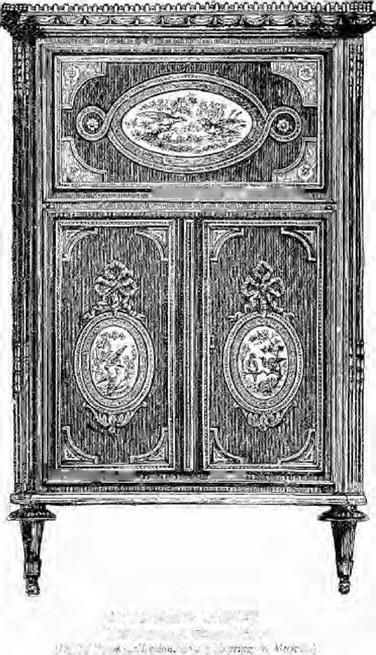

A notable feature in the ornament of woodwork and in metal mountings of this time, is a fluted pilaster with quills or husks filling the flutings some distance from the base, or starting from both base and top and leaving an interval of the hollow fluting plain and free. An example of this will be seen in the next woodcut of a cabinet in the Jones collection, which has also the familiar "Louis Seize" riband surmounting the two oval Sevres china plaques. When the flutings are in oak, in rich mahogany, or painted white, these husks are gilt, and the effect is chaste and pleasing. Variation was introduced into the gilding of frames by mixing silver with some portion of the gold so as to produce two tints, red gold and green gold; the latter would be used for wreaths and accessories, while the former, or ordinary gilding, was applied to the general surface. The legs of tables are generally fluted, as noticed above, tapering towards the feet, and are relieved from a stilted appearance by being connected by a stretcher.

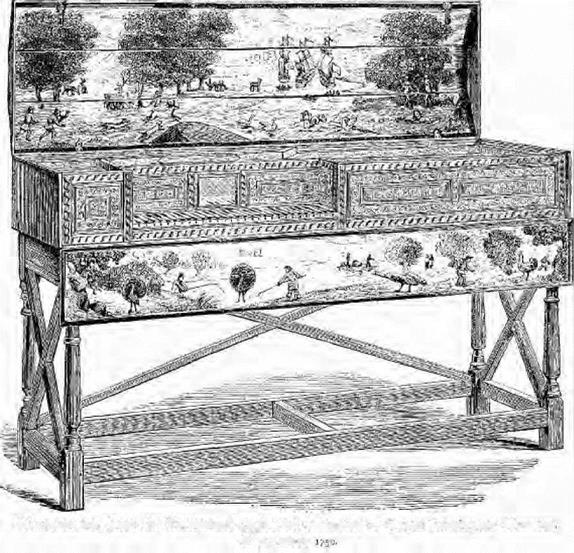

There occurs in M. Williamson’s valuable contribution to the literature of our subject ("Lee Meubles d’Art du Mobilier National,") an interesting illustration of the gradual alterations which we are noticing as having taken place in the design of furniture. This is a small writing table, some 3 ft. 6 in. long, made during the reign of Louis XV., but quite in the Marie Antoinette style, the legs tapering and fluted, the frieze having in the centre a plaque of bronze dore, the subject being a group of cupids, representing the triumph of Poetry, and on each side a scroll with a head and foliage (the only ornament characteristic of Louis Quinze style) connecting leg and frieze. M. Williamson quotes verbatim the memorandum of which this was the subject. It was made for the Trianon and the date is just one year after Marie Antoinette’s marriage:—"Memoire des ouvrages faits et livres, par les ordres de Monsieur le Chevalier de Fontanieu, pour le garde meuble du Roy par Riesener, ebeniste a l’arsenal Paris," savoir Sept. 21, 1771; and then follows a fully detailed description of the table, with its price, which was 6,000 francs, or £240. There is a full page illustration of this table.

The maker of this piece of furniture was the same Riesener whose masterpiece is the magnificent Bureau du Roi which we have already alluded to in the Louvre. This celebrated ebeniste continued to work for Marie Antoinette for about twenty years, until she quitted Versailles, and he probably lived quite to the end of the century, for during the Revolution we find that he served on the Special Commission appointed by the National Convention to decide which works of Art should be retained and which should be sold, out of the mass of treasure confiscated after the deposition and execution of the King.

^ттгэзйиетявяшяп

^ттгэзйиетявяшяп

ULilL

|(АтгГЁ}::; O-PUf ГТ Wihb! Punqtfe! ЦГ t, – tecs C. b.m. ■■ г !"■■.’ ■’ t, Fi. i‘S’ Л’.-і!:■ ■………………………. :■■■■■.

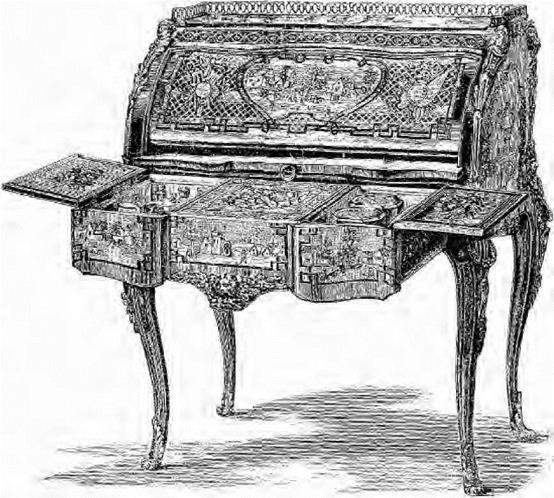

Riesener’s designs do not show much fertility, but his work is highly finished and elaborate. His method was generally to make the centre panel of a commode front, or the frieze of a table, a tour de force, the marqueterie picture being wonderfully delicate. The subject was generally a vase with fruits and flowers; the surface of the side panels inlaid with diamond-shaped lozenges, or a small diaper pattern in marqueterie; and then a framework of rich ormolu would separate the panels. The centre panel had sometimes a richer frame. His famous commode, made for the Chateau of Fontainebleau, which cost a million francs (£4,000)—an enormous sum in those days—is one of his chefs d’oeuvre, and this is an excellent example of his

style. A similar commode was sold in the Hamilton Palace sale for £4,305. An upright secretaire, en suite with the commode, was also sold at the same time for £4,620, and the writing table for £6,000. An illustration of the latter is on the following page, but the details of this elaborate gem of cabinet maker’s work, and of Gouthiere’s skill in mounting, are impossible to reproduce in a woodcut. It is described as follows in Christie’s catalogue:—

|

|

"Lot 303. An oblong writing table, en suite, with drawer fitted with inkstand, writing slide and shelf beneath; an oval medallion of a trophy and flowers on the top, and trophies with four medallions round the sides: stamped T. Riesener and branded underneath with cypher of Marie Antoinette, and Garde Meuble de la Reine." There is no date on the table, but the secretaire is stamped 1790, and the commode 1791. If we assume that the table was produced in 1792, these three specimens, which have always been regarded as amongst the most beautiful work of the reign, were almost the last which the unfortunate Queen lived to see completed.

|

Til I – АїїЄіЗ. ЧЛГЇЕ " WfilTWft T**Ll-. ■ Vt, i ijrr h.’i :<■ Hi-. И c i.’v.1: г і; Fitloft MffatflOilJ |

The fine work of Riesener required the mounting of an artist of quite equal merit, and in Gouthiere he was most fortunate. There is a famous clock case in the Hertford collection, fully signed "Gouthiere, ciseleur et doreur du roi a Paris Quai Pelletier, a la Boucle d’or, 1771." He worked, however, chiefly in conjunction with Riesener and David Roentgen for the decoration of their marqueterie.

In the Louvre are some beautiful examples of this co-operative work; and also of cabinets in which plaques of very fine black and gold lacquer take the place of marqueterie; the centre panel being a finely chased oval medallion of Gouthiere’s gilt bronze, with caryatides figures of the same material at the ends supporting the cornice.

BEDSTEAD OF MARIE ANTOINETTE

BEDSTEAD OF MARIE ANTOINETTE

f-fvjjn ifontuinubicau Co||c> <l"ii • МчЬііізг aUobJil "

{f’nDii а і ічі o n<i і aft tloi/ring it і l Jirnis)

J’liLiii. iij ■ Lui is XVt

|

‘ VI fcttn&lf >K(. i::-i’lі 1-ї-. 111 lVJh І ці hi i.’.’ill 0j. tj;JL і і : Л’і ці in.. ijy jaLTUOCfi ir, tiff ml № іЗсійЙ’М^’И 11 г. H LTIIt. І MU Hi YVli |

A specimen of this kind of work (an upright secretaire, of which we have not been able to obtain a satisfactory representation) formed part of the Hamilton Palace collection, and realised £9,450, the highest price which the writer has ever seen a single piece of furniture bring by auction; it must be regarded as the chef d’oeuvre of Gouthiere.

In the Jones Collection, at South Kensington, there are also several charming examples of Louis Seize meubles de luxe. Some of these are enriched with plaques of Sevres porcelain, which treatment is better adapted to the more jewel-like mounting of this time than to the rococo style in vogue during the preceding reign.

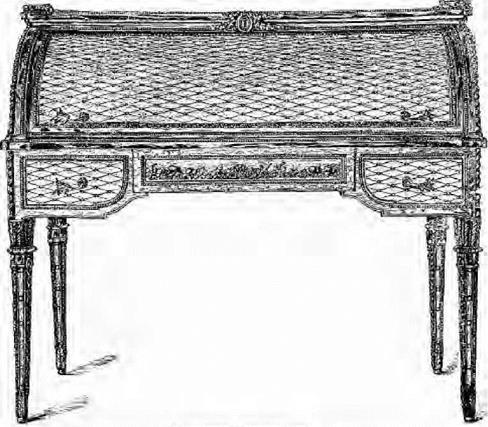

The upholstered furniture became simpler in design; the sofas and chairs have generally, but not invariably, straight fluted tapering legs, but these sometimes have the flutings spiral instead of perpendicular, and the backs are either oval or rectangular, and ornamented with a carved riband which is represented as tied at the top in a lover’s knot. Gobelins, Beauvais, and Aubusson tapestry are used for covering, the subjects being in harmony with the taste of the time. A sofa in this style, with settees at the ends, the frame elaborately carved with trophies of arrows and flowers in high relief, and covered with fine old Gobelins tapestry, was sold at the Hamilton Palace sale for £1,176. This was formerly at Versailles. Beautiful silks and brocades were also extensively used both for chairs and for the screens, which at this period were varied in design and extremely pretty. Small two-tier tables of tulip wood with delicate mountings were quite the rage, and small occasional pieces, the legs of which, like those of the chairs, are occasionally curved. An excellent example of a piece with cabriole legs is the charming little Marie Antoinette cylinder-fronted marqueterie escritoire in the Jones Collection (illustrated below). The marqueterie is attributed to Riesener, but, from its treatment being so different from that which he adopted as an almost invariable rule, it is more probably the work of David.

|

|

Another fine specimen illustrated on page 170 is the small cabinet made of kingwood, with fine ormolu mounts, and some beautiful Sevres plaques.

t uvurvi! nmIq DcaUvntn fapi^iry (СоПи. ЧІоіі 1 Mo biller National.’ r

t uvurvi! nmIq DcaUvntn fapi^iry (СоПи. ЧІоіі 1 Mo biller National.’ r

(rrw»i t rrti Ціні w dwttMttjr h H, іїігиил l

PeRI«‘I>, LnIi и»- l. uUlwv’1

|

CAHVED AND GILT CANAPE OH SOFA,

Cuv’r«"1 with Неачгаїк iaj tsir (L-jllti-liui! 1 Mulviiit” XMloaftl ‘i

Pvnmil I’Ikii ‘<v I. і’. Л’І

|

■■I iiiCT’TT ‘-TR с. By David. ■Mid ir Iiryi: Ьгіілцїєіі гг* Шиііп Аліоіцчіу C’.’ifiLti’.- :. ;ii’Jr.‘.’V Л’йПії’; . :■ – л ~j,.v-‘ |

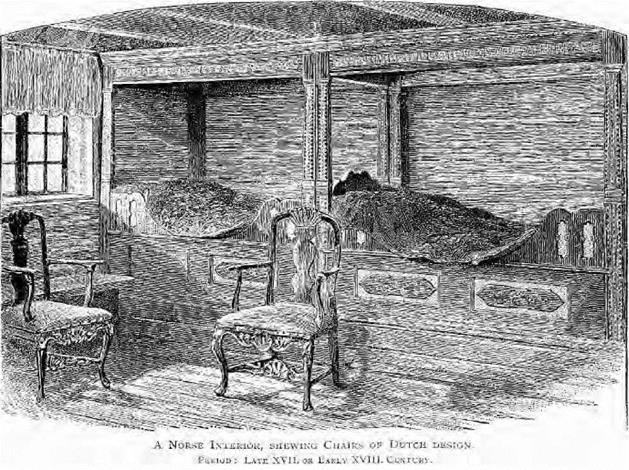

The influence exercised by the splendour of the Court of Louis Quatorze, and by the bringing together of artists and skilled handicraftsmen for the adornment of the palaces of France, which we have seen took place during the latter half of the seventeenth century, was not without its effect upon the Industrial Arts of other countries. Macaulay mentions the "bales of tapestry" and other accessories which were sent to Holland to fit up the camp quarters of Louis le Grand when he went there to take the command of his army against William III., and he also tells us of the sumptuous furnishing of the apartments at St. Germains when James II., during his exile, was the guest of Louis. The grandeur of the French King impressed itself upon his contemporaries, and war with Germany, as well as with Holland and England, helped to spread this influence. We have noticed how Wren designed the additions to Hampton Court Palace in imitation of Versailles; and in the chapter which follows this, it will be seen that the designs of Chippendale were really reproductions of French furniture of the time of Louis Quinze. The King of Sweden, Charles XII., "the Madman of the North," as he was called, imitated his great

French contemporary, and in the Palace at Stockholm there are still to be seen traces of the Louis Quatorze style in decoration and in furniture; such adornments are out of keeping with the simplicity of the habits of the present Royal family of Sweden.

A Bourbon Prince, too, succeeded to the throne of Spain in 1700, and there are still in the palaces and picture galleries of Madrid some fine specimens of French furniture of the three reigns which have just been discussed. It may be taken, therefore, that from the latter part of the seventeenth century the dominant influence upon the design of decorative furniture was of French origin.

There is evidence of this in a great many examples of the work of Flemish, German, English, and Spanish cabinet makers, and there are one or two which may be easily referred to which it is worth while to mention.

One of these is a corner cupboard of rosewood, inlaid with engraved silver, part of the design being a shield with the arms of an Elector of Cologne; there is also a pair of somewhat similar cabinets from the Bishop’s Palace at Salzburg. These are of German work, early eighteenth century, and have evidently been designed after Boule’s productions. The shape and the gilt mounts of a secretaire of walnutwood with inlay of ebony and ivory, and some other furniture which, with the other specimens just described, may be seen in the Bethnal Green Museum, all manifest the influence of the French school, when the bombe-fronted commodes and curved lines of chair and table came into fashion.

Having described somewhat in detail the styles which prevailed and some of the changes which occurred in France, from the time of Louis XIV. until the Revolution, it is unnecessary for the purposes of this sketch, to do more than briefly refer to the work of those countries which may be said to have adopted, to a greater or less extent, French designs. For reasons already stated, an exception is made in the case of our own country; and the following chapter will be devoted to the furniture of some of the English designers and makers of the latter half of the eighteenth century. Of Italy it may be observed generally that the Renaissance of Raffaele, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michael Angelo, which we have seen became degenerate towards the end of the sixteenth century, relapsed still further during the period which we have been discussing, and although the freedom and grace of the Italian carving, and the elaboration of inlaid arabesques, must always have some merit of their own, the work of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Italy will compare very unfavourably with that of the earlier period of the Renaissance.

|

|

There are many other museum specimens which might be referred to to prove the influence of French design of the seventeenth and subsequent centuries on that of other countries. The above illustration of a Norse interior shews that this influence penetrated as far as Scandinavia; for while the old-fashioned box-like bedsteads which the Norwegians had retained from early times, and which in a ruder form are still to be found in the cottages of many Scottish counties, especially of those where the Scandinavian connection existed, is a characteristic mark of the country, the design of the two chairs is an evidence of the innovations which had been made upon native fashions. These chairs are in style thoroughly Dutch, of about the end of the seventeenth or early in the eighteenth century; the cabriole legs and shell ornaments were probably the direct result of the influence of the French on the Dutch. The woodcut is from a drawing of an old house in Norwav.

It would be unfitting to close this chapter on French furniture without paying a tribute to the munificence and public spirit of Mr. John Jones, whose bequest to the South Kensington Museum constitutes in itself a representative Museum of this class of decorative furniture. Several of the illustrations in this chapter have been taken from this collection.

|

ЬзКСВКТЛіЯЕ, L;i ІСІ nflL – а-іІ-Л Tulljp ‘Л’.’ЪиД ‘.’.lT, Иіч,:ti- and OfniOla ї>Г пці^іїл й. Г1.-loU: 1 л і-: .■_ ЬО’ІДЙ Xі – J |

In money value alone, the collection of furniture, porcelain, bronzes, and articles de vertu, mostly of the period embraced within the limits of this chapter, amounts to about £400,000, and exceeds the value of any bequest the nation has ever had. Perhaps the references contained in these few pages to the French furniture of this time may stimulate the interest of the public in, and its appreciation of, this valuable national property.

Soon after this generous bequest was placed in the South Kensington Museum, for the benefit of the public, a leading article appeared in the Times, from which the following extract will very appropriately conclude this chapter:—"As the visitor passes by the cases where these curious objects are displayed, he asks himself what is to be said on behalf of the art of which they are such notable examples." Tables, chairs, commodes, secretaires, wardrobes, porcelain vases, marble statuettes, they represent in a singularly complete way the mind and the work of the ancien regime. Like Eisen’s vignettes, or the contes of innumerable story-tellers, they bring back to us the grace, the luxury, the prettiness, the frivolity of that Court which believed itself, till the rude awakening came, to contain all that was precious in the life of France. A piece of furniture like the little Sevres-inlaid writing table of Marie Antoinette is, to employ a figure of Balzac’s, a document which reveals as much to the social historian as the skeleton of an ichthyosaurus reveals to the paleontologist. It sums up an epoch. A whole world can be inferred from it. Pretty, elegant, irrational, and entirely useless, this exquisite and costly toy might stand as a symbol for the life which the Revolution swept away.

|

|

НлЕтаїсно’кв, &ао] the p-ennanttit CulJcctfon brcinotfiiig to гіоиііі Kenyiagton ItjMSiiteL

ОлТЫ iUwL-t

Ebd

E-BooksDirectory. com

E-BooksDirectory. com

|

|

|